The Death of Rev. Isaac Backus, November 21, 1806

![]() t has become fashionable among historians, including some Christian ones, to denigrate the “Great Awakening” as evidence of a mere psychological phenomenon in American history, associated with certain preachers of a new and hysterical evangelicalism in the mid-18th century. One book views George Whitefield as a master of religious marketing, and the responses to his preaching emotion-driven aberrations from orthodox preaching and historic Protestant pulpit ministry. If that was all that such spiritual awakenings consisted of, changed lives would likely be short-term and the Church itself relatively unaffected over the long-term. Controversial in the era in which it occurred, the Great Awakening (not called that till a book of that title was published in the 1840s) did result in real lifelong and life-changing conversions which profoundly affected individuals and churches. One of the most prominent was Isaac Backus, who died on this day in 1806.

t has become fashionable among historians, including some Christian ones, to denigrate the “Great Awakening” as evidence of a mere psychological phenomenon in American history, associated with certain preachers of a new and hysterical evangelicalism in the mid-18th century. One book views George Whitefield as a master of religious marketing, and the responses to his preaching emotion-driven aberrations from orthodox preaching and historic Protestant pulpit ministry. If that was all that such spiritual awakenings consisted of, changed lives would likely be short-term and the Church itself relatively unaffected over the long-term. Controversial in the era in which it occurred, the Great Awakening (not called that till a book of that title was published in the 1840s) did result in real lifelong and life-changing conversions which profoundly affected individuals and churches. One of the most prominent was Isaac Backus, who died on this day in 1806.

A scene from the First Great Awakening — George Whitfield preaches to a crowd near Bolton, England

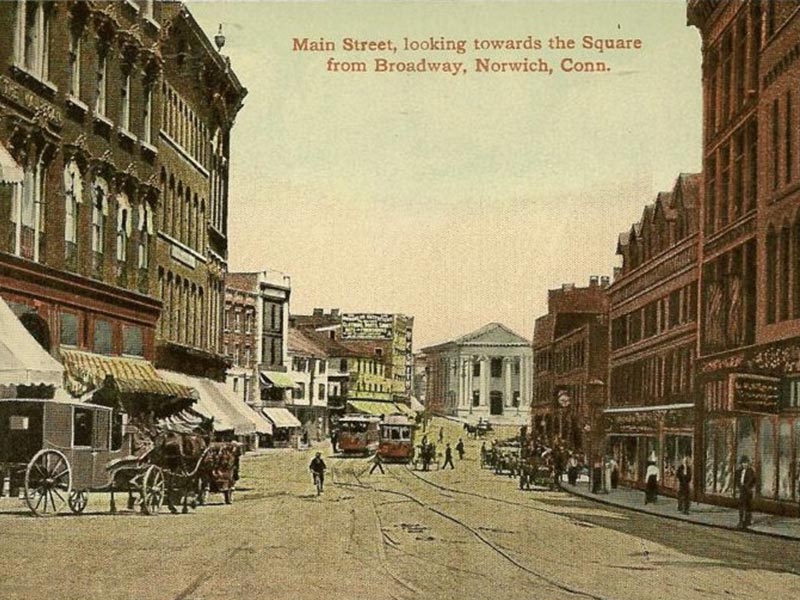

Backus was born into a typical Norwich, Connecticut Congregationalist farm family in 1724. The larger Backus family of grandparents, father, uncles, and cousins provided the region with a sawmill, gristmill, general store, ironworks, and blacksmith shops as well as sheep herds, orchards and produce. The Backuses served in local government, the colonial legislature, and militias. One became a minister and married Jonathan Edwards’s sister, another married a Revolutionary War general. Isaac was the fourth of eleven children. Life on the farm made him strong and healthy, church attendance and catechizing made him knowledgeable but unconverted till his seventeenth year.

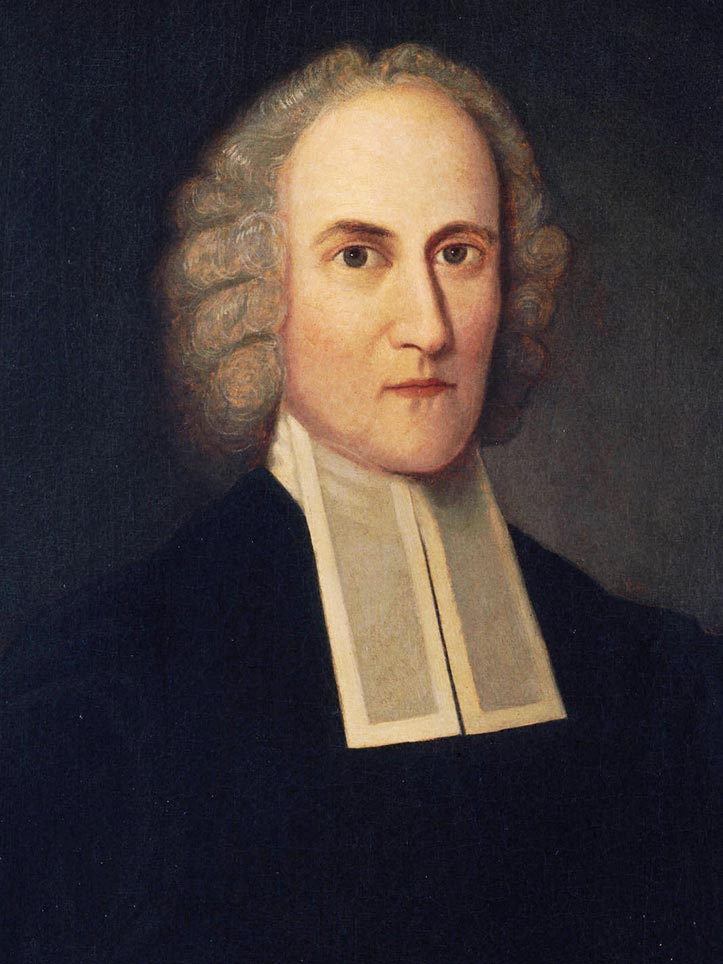

Isaac Backus (1724-1806)

The preaching of George Whitefield, Jonathan Edwards and other “revivalist” preachers found open pulpits and eager parishioners all across the Connecticut Valley, including the Congregationalist church in Norwich. Isaac later said that “his soul was drawn to Christ and his righteousness and . . . my burden of sin was gone,” a testimony made by multiple thousands of Americans in all thirteen colonies over several years of powerful Gospel preaching. Young Isaac Backus soon joined a Separate congregation and pursued a call to be a preacher himself. Later joining the Baptists, the former farm-boy became one of the most powerful preachers during the days of American independence and beyond. He was to preach for more than sixty years and travel more than 70,000 miles! Backus served as a trustee for what became Brown University in Rhode Island, a Baptist stronghold.

George Whitefield (1714-1770)

Jonathan Edwards (1703-1758)

From 1769 Isaac Backus played a key intellectual and practical role toward securing independence from England and religious liberty for Christians who dissented from the established churches. He wrote tracts, petitions and letters. He fought for the disestablishment of the Congregationalist Church, a fight he would not live to see consummated twenty years after his death. The most important of the thirty-seven tracts he published was An Appeal to the Public for Religious Liberty Against the Oppression of the Present Day (1773). His fight on that front is often likened to the efforts of George Mason and Thomas Jefferson in Virginia, but from a perspective that sought a thoroughly Christian civil government.

Main Street Norwich, Connecticut in 1916

Backus was fifty-one when the Revolutionary War began. He led the New England Baptists as Patriots in support of independence, but always with the hope for religious liberty to go along with the political. During and especially after the war, Backus defended a strict Calvinist theology against the deism and Arminianism that had made inroads among Baptists in the new nation. His apologetical sermons and tracts focused on what he considered the largest threats of the Reformed Baptists: Shakers, Universalists, Methodism, and Free-Will Baptists. As a delegate to the Ratification of the Constitution Convention in Massachusetts, Backus reluctantly supported ratification with the promise of amendments guaranteeing religious freedom and other important rights.

Isaac Backus supported the Jeffersonian Republicans in the midst of a solidly Federalist New England. He defied John Adams and the others regarding the continued establishment of the Congregationalist Church and he strongly supported, along with “Trinitarian Congregationalists” the application of biblical law regarding the Sabbath, and laws against profanity, gambling, and drunkenness. Isaac died at eighty-two, known by all who knew him, as “Father.” One of his biographers concludes the summary of the life of Isaac Backus:

“[His] importance lies beyond his relationship to his denomination or to the movement to separate Church and State. It lies in his almost perfect embodiment of the evangelical spirit of his times. . . Few men expressed so well in thought and action that vigorous, fervent, conscientious, experimental pietism which constituted the fundamental spirit of the new nation and which made its experiment in freedom unique.” (Isaac Backus, by Williams G. McLoughlin)