“I will teach transgressors your ways, and sinners will be converted to you.” —Psalm 51:13

The Birth of Richard Baxter, November 14, 1615

![]() n God’s good providence, the seventeenth century produced many great preachers of the Gospel, especially in England and Scotland. They were born in times of persecution and trouble, to be sure, but as the conveyors of the Reformation faith of the previous century, those men left behind books, sermons, pamphlets, and speeches — not to mention examples of courage and sacrifice — that have inspired the Church for centuries. Unlike his contemporaries, Richard Baxter did not attend Oxford; he attached himself to a country chaplain at Ludlow near his birthplace in Shropshire, and learned primarily as an autodidact, just studying the Scriptures on his own and reading books in the considerable library of the Castle, on a promontory overlooking River Teme. In time he would become the most powerful and most prolific of all the English Puritans.

n God’s good providence, the seventeenth century produced many great preachers of the Gospel, especially in England and Scotland. They were born in times of persecution and trouble, to be sure, but as the conveyors of the Reformation faith of the previous century, those men left behind books, sermons, pamphlets, and speeches — not to mention examples of courage and sacrifice — that have inspired the Church for centuries. Unlike his contemporaries, Richard Baxter did not attend Oxford; he attached himself to a country chaplain at Ludlow near his birthplace in Shropshire, and learned primarily as an autodidact, just studying the Scriptures on his own and reading books in the considerable library of the Castle, on a promontory overlooking River Teme. In time he would become the most powerful and most prolific of all the English Puritans.

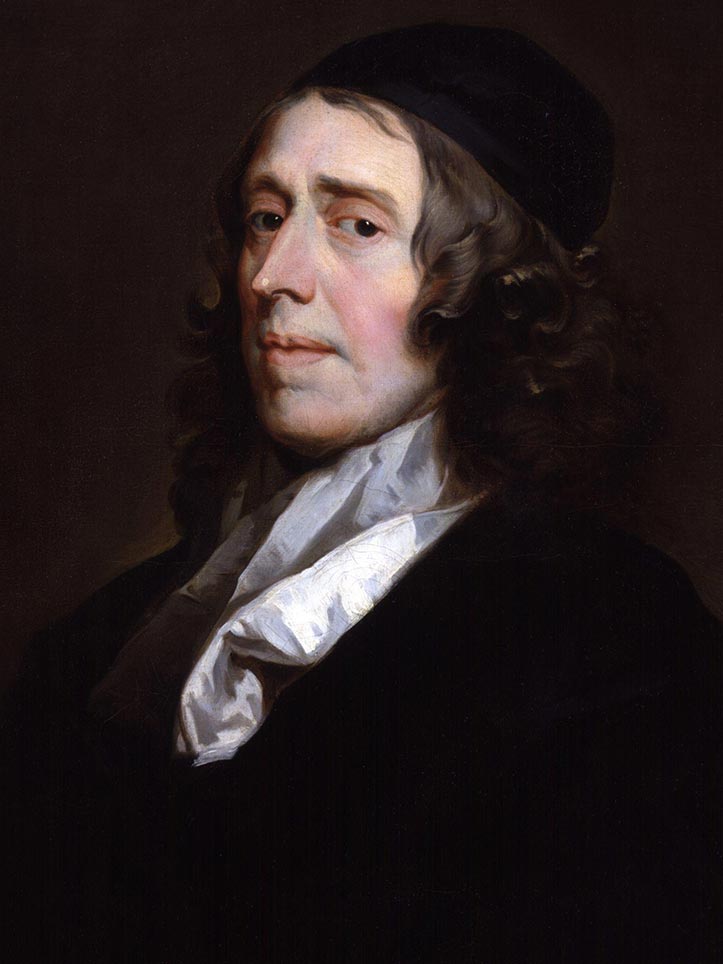

Richard Baxter (1615-1691)

17th-century English Puritan, theologian and church leader

John Owen (1616-1683)

At the advice of Owen, schoolmaster at Wroxeter, Baxter opted not to attend Oxford

Baxter received tutoring from different local clergy and was eventually ordained by the Bishop of Worcester. In conversations with several dissenting ministers in the 1630s, Richard Baxter began to move away from some of the superstitions and appurtenances of established Anglicanism. Baxter developed a preaching style that was at once fervent and evangelistic, distinguishing him from the typical Anglican rector. As assistant pastor, he was excused from duties he considered unlawful. In 1641 Baxter was invited to become lecturer at St. Mary’s in Kidderminster, with a congregation of three thousand; so powerful did Baxter’s ministry there become that one observer commented that “among the moral (much less the godly) were to be counted on ten fingers, ere very long a passing traveler along the streets at a given hour heard the sounds of praise and praise in every household.”

Ludlow Castle

When the English Civil Wars began, Baxter sided with Parliament in a largely loyalist county, so he moved near a garrison of Parliamentary troops and preached to them every Sunday, and to the townsmen later the same day. Oliver Cromwell’s Cavalry officers asked the Kidderminster pastor to become the pastor of their troop, as if a church, an offer Baxter rejected as unbiblical. He continued serving as army chaplain on campaign and eventually developed a severe illness, he thought would likely prove fatal. Baxter retired from the service to seek recovery. In that time he wrote the first of his 168 books, The Saints’ Everlasting Rest, which proved to be a Christian classic, still in print. Richard survived his illness and served his Kidderminster Church with untiring zeal from 1647-1660, catechizing, with an assistant, eight hundred families every year, beside all his preaching duties and writing.

St. Mary’s Church in Kidderminster

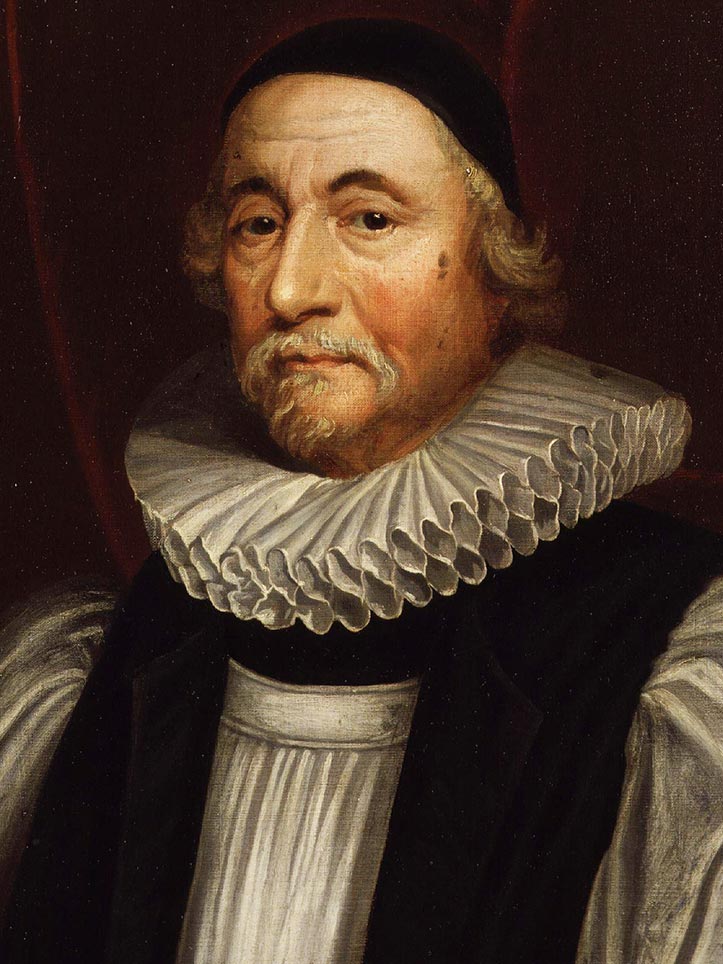

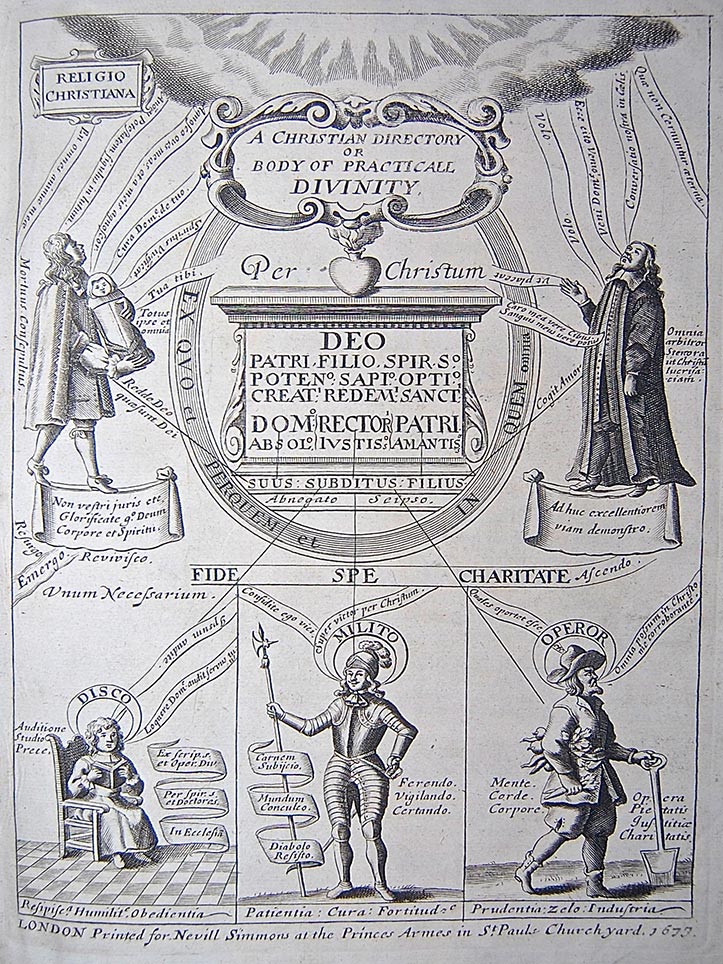

At the urging of Archbishop James Ussher, he “produced a directory for afflicted consciences, appealing to the unconverted and to all ranks of professing Christians,” which became a popular work known as A Christian Directory. He remained a critic of Cromwell and other Independents, especially the radicals that had come out of the war. He preached before the Lord Protector but their relationship remained cool. As a moderate, Baxter was among the preachers called by Parliament to welcome the return of Charles II to the throne; he became one of only four men who preached before the King. Baxter rejected a bishopric and was expelled from his pulpit in the 1662 Act of Conformity imposed on all the Puritan preachers.

James Ussher (1581-1656)

Archbishop of Armagh and Primate of All Ireland

Baxter’s seminal work, A Christian Directory, Or Body of Practical Divinity

Richard Baxter was jailed a number of times for preaching in violation of the sanctions against him. He continued to write, even in prison. Hauled before the notorious Judge “Bloody” Jeffries as a Non-conformist rebel preacher, the judge said, “Richard, I see the rogue in your face.” Baxter shot back, “I did not know my face was such a true mirror.” After the Glorious Revolution and the accession of William and Mary to the throne, Baxter continued preaching till he died. Baxter’s outspokenness and attempts to steer middle courses in politics and theology got him into constant trouble in his own day and among Reformed scholars to the present. He wrote toward the end of his life that “the Gospel dieth not when I die; the church dieth not; the World dieth not; . . . and it may be that some of the seed that I have sown shall spring up to some benefit of the dark unpeaceable world when I am dead.” It has.