“Not by works of righteousness which we have done, but according to his mercy he saved us, by the washing of regeneration, and renewing of the Holy Ghost; which he shed on us abundantly through Jesus Christ our Savior; that being justified by his grace, we should be made heirs according to the hope of eternal life.” —Titus 3:5-7

The Synod of Dort Begins,

November 13, 1618

nce the Protestant Reformation of the 16th Century had swept across Europe, various countries were able to stabilize their borders and establish their new-found faith, although political and social contention persisted. Romanist heresies within Protestantism continued to challenge the Church, and the theologians’ and pastors’ need to systematize biblical doctrine continued well into the next century. Reformed confessions emerged to define what Protestant Christians believed. In the Netherlands, which had adopted a strong Calvinist theology in the “Belgic Confession of Faith” of 1561 (which had been primarily written by Dutch pastor Guido de Bres), challenges arose which caused disruption in the churches. James Arminius, a Dutch pastor and University professor presented the greatest theological challenge since the expulsion of the Roman Church.

nce the Protestant Reformation of the 16th Century had swept across Europe, various countries were able to stabilize their borders and establish their new-found faith, although political and social contention persisted. Romanist heresies within Protestantism continued to challenge the Church, and the theologians’ and pastors’ need to systematize biblical doctrine continued well into the next century. Reformed confessions emerged to define what Protestant Christians believed. In the Netherlands, which had adopted a strong Calvinist theology in the “Belgic Confession of Faith” of 1561 (which had been primarily written by Dutch pastor Guido de Bres), challenges arose which caused disruption in the churches. James Arminius, a Dutch pastor and University professor presented the greatest theological challenge since the expulsion of the Roman Church.

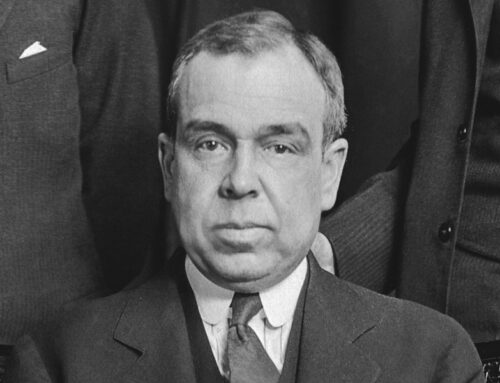

James Arminius (1560–1609)

Arminius was a highly respected theologian and pastor in the Reformed Church of the Netherlands. He was noted for his “activity, intelligence, wit, and obliging deportment”. He was sent to the University in Geneva, where he sat under Theodore Beza, Calvin’s successor. Of independent mind and possessed of an insubordinate disposition, he developed theological views that differed from his professors, and he embarked behind the scenes to lead fellow students away from the Genevan orthodoxy. He was sent home. After travelling in Italy for ten months, he returned to Holland where he was greeted with great acclaim and a request to answer a tract by Dutch pastors who opposed the Reformed view of predestination. He ended up accepting the argument of the dissenters. In a series of sermons from his church pulpit, on the Book of Romans, he publicly abandoned the position of the Belgic churches.

Theodore Beza (1519–1605)

Although Arminius was rebuked by his Classis (presbytery), he continued to teach behind the scenes. His “learning, smooth address, and insinuating eloquence” won over a number of dissidents to take a stand against certain established Protestant doctrines. Some of his many friends were able to massage the volatile situation and Arminius was able to retain his preaching position. Every attempt to get Arminius into open theological debate was rebuffed through evasion, excuses, and subterfuge. As Samuel Miller of Princeton so succinctly observed, “the commencement of every heresy which has arisen in the Christian church” began with “a want of candor and integrity on the part of a man otherwise respectable . . . it is never frank and open”.

An allegorical depiction of the theological debate between “Remonstrants”—as followers of the teachings of Arminius called themselves— and their Dutch Reformed opponents. The Dutch Reformed side of the scale is heavier, but only on account of the extra weight added by a sword, representing the external influence of the state.

Because the Reformed Church was a state church, the politicians took a hand in the controversy and the Estates General called for Arminius and his companions, in 1609, to appear before them and explain his unorthodox theology. Before they could meet, Arminius died. His followers took the doctrines he had expounded, and continued preaching and teaching them in the universities and the churches, creating an uproar in the churches, and even dividing the national legislature. The Arminians drew up their doctrinal aberrations in a document known as the Remonstrance. The Church and State finally called a great Synod at the City of Dort beginning on November 13, 1618, to state for all the church what the Bible teaches concerning the doctrines under attack by the Arminians.

Johannes Wtenbogaert (1557-1644) became leader of the “Remonstrants” after the death of James Arminius in 1609 and drew up the document known as the Five Articles of Remonstrance in 1610. The point-by-point rebuttal to this document was issued in the Canons of Dort of 1618-19, the substance of which has come to be referred to as the Five Points of Calvinism.

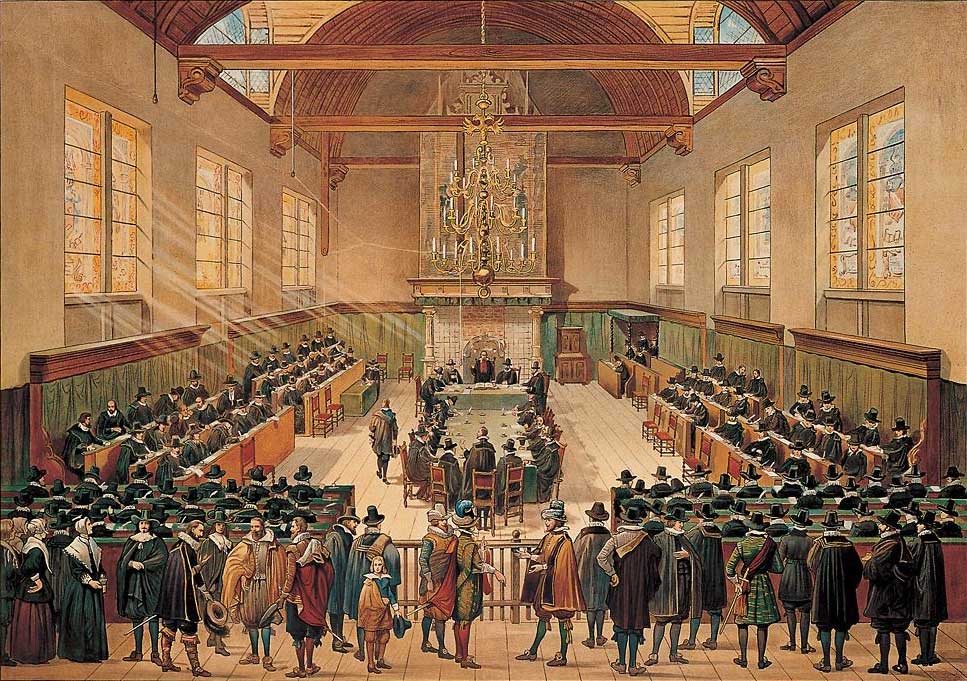

The Synod of Dort, with Arminians seated at a table in the center

Holland invited scholars from all the Reformed countries to participate also. The “divines” sat in solemn ecclesiastical deliberations, and prayer and preaching, meeting one hundred eighty times. They concluded the assembly on May 29, 1619, having examined every aspect of the Remonstrance, and interviewed the Arminian pastors. The Synod produced the Canons of Dort, addressing each point of the Arminians’ beliefs regarding the doctrine of salvation. [See article here to compare the Arminian and the Calvinist positions on these theological points.]

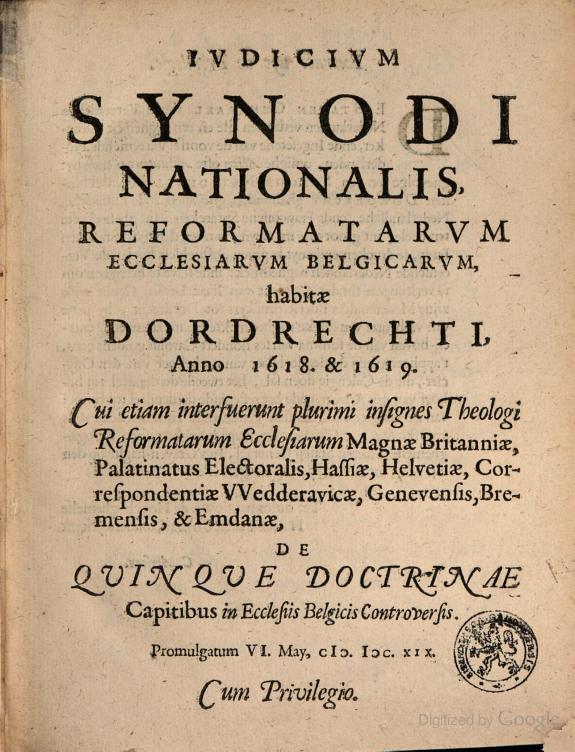

Title page of the Canons of Dort

The international Synod unanimously condemned the Arminians’ arguments, and the Canons of Dort helped inform future Calvinist Confessions on the continent and in the United Kingdom. Nonetheless, the Arminian beliefs continued to spread wherever the Reformation succeeded, and eventually permeated Protestant thinking in England and America, especially among denominations who rejected the Reformed Confessions. Men seem to have a compulsion to declare their independence from God in all things, including their own salvation. That does not change the fact that changing the hearts of the elect, and giving them the gift of Faith through His Grace, is solely an activity of the Sovereign God, who is not confined by the whims of His created image-bearers.

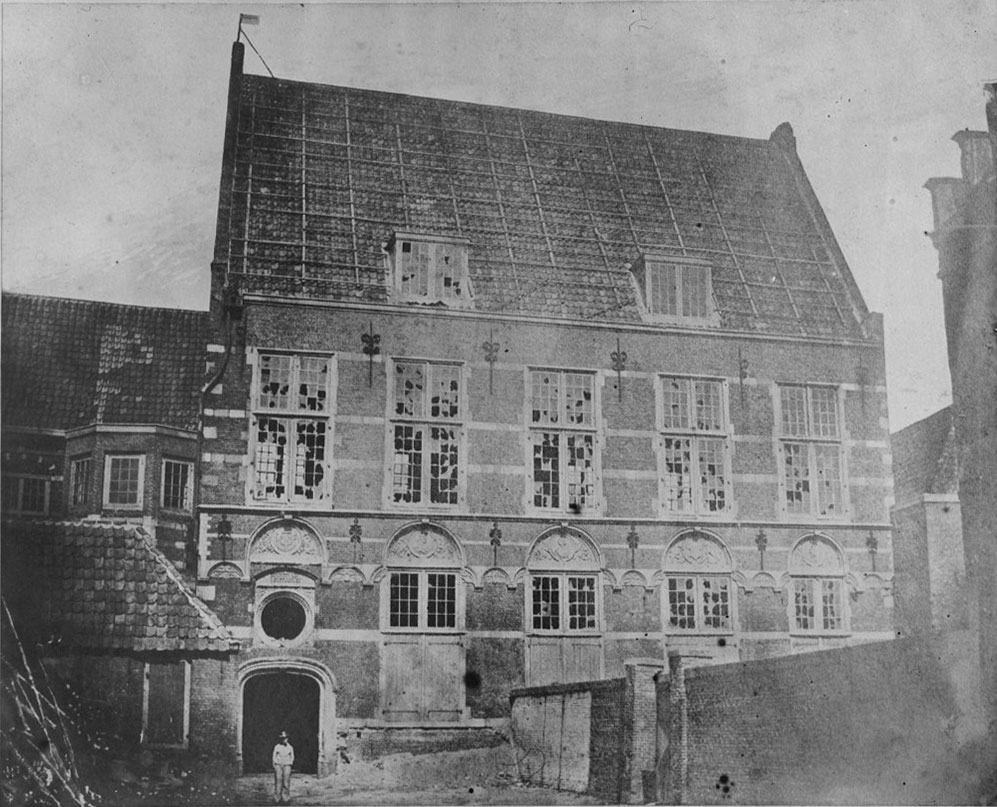

The Kloveniersdoelen, location of the Synod of Dort assembly, before its demolition in 1857

For a nice summary of the Synod of Dort, see A Place Like Heaven: An Introduction to the Synod of Dort, by Samuel Miller.

Image Credits: 1 James Arminius (Wikipedia.org) 2 Theodore Beza (Wikipedia.org) 3 Remonstrants (Wikipedia.org) 4 Johannes Wtenbogaert (Wikipedia.org) 5 Synod of Dort Assembly (Wikipedia.org) 6 Kloveniersdoelen (Wikipedia.org) 7 Canons of Dort Title Page (Wikipedia.org)