The Gettysburg Address, November 19, 1863

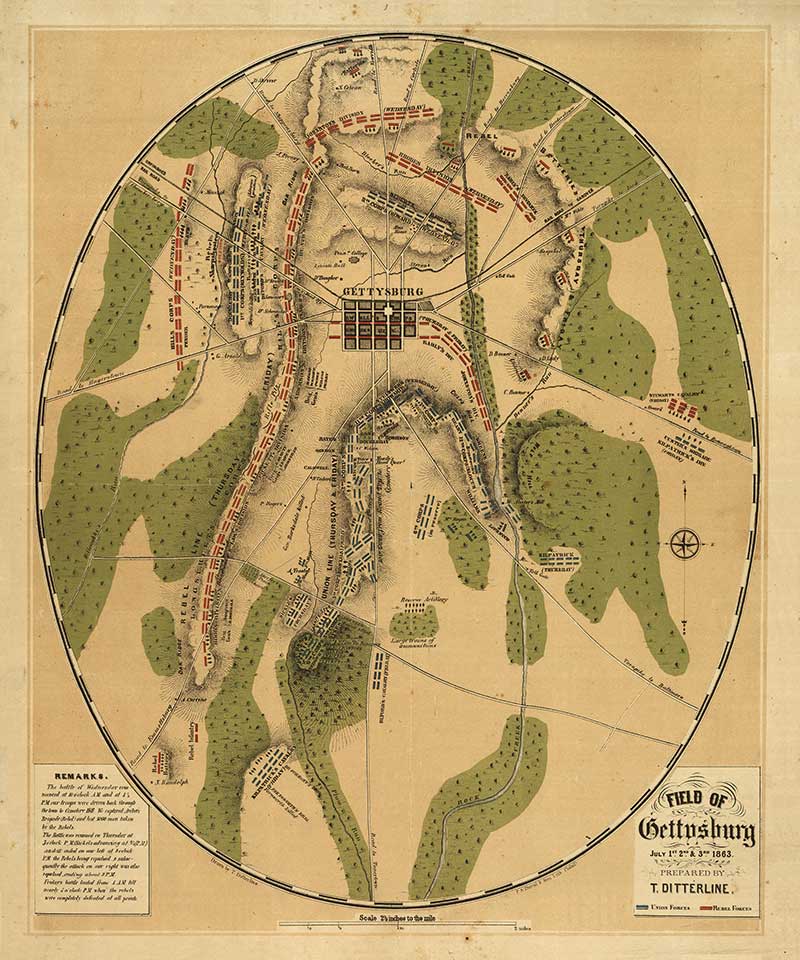

![]() he events of July 1-3, 1863 in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, forever changed the historical landscape of America. General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia and Major General George Meade’s Army of the Potomac—about 150,000 men total—stood toe to toe and slaughtered each other, producing more than 46,000 casualties, of whom, perhaps 10,000, a large percentage teenagers, were dead on the field, and many more perished in the following days—more American deaths from battle in three days than the entire number of battle deaths in the eight years of the War for American Independence. The Southern Army retreated back to Virginia. The Northerners, just as exhausted, stopped at the Potomac River. The entire nation stood in shock for months to follow.

he events of July 1-3, 1863 in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, forever changed the historical landscape of America. General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia and Major General George Meade’s Army of the Potomac—about 150,000 men total—stood toe to toe and slaughtered each other, producing more than 46,000 casualties, of whom, perhaps 10,000, a large percentage teenagers, were dead on the field, and many more perished in the following days—more American deaths from battle in three days than the entire number of battle deaths in the eight years of the War for American Independence. The Southern Army retreated back to Virginia. The Northerners, just as exhausted, stopped at the Potomac River. The entire nation stood in shock for months to follow.

Map of the Gettysburg Battlefield as it appeared at the time of the battle, July 1-3, 1863, showing detailed notes of terrain, local farms, etc.

Soldiers’ National Monument at the center of Gettysburg National Cemetery

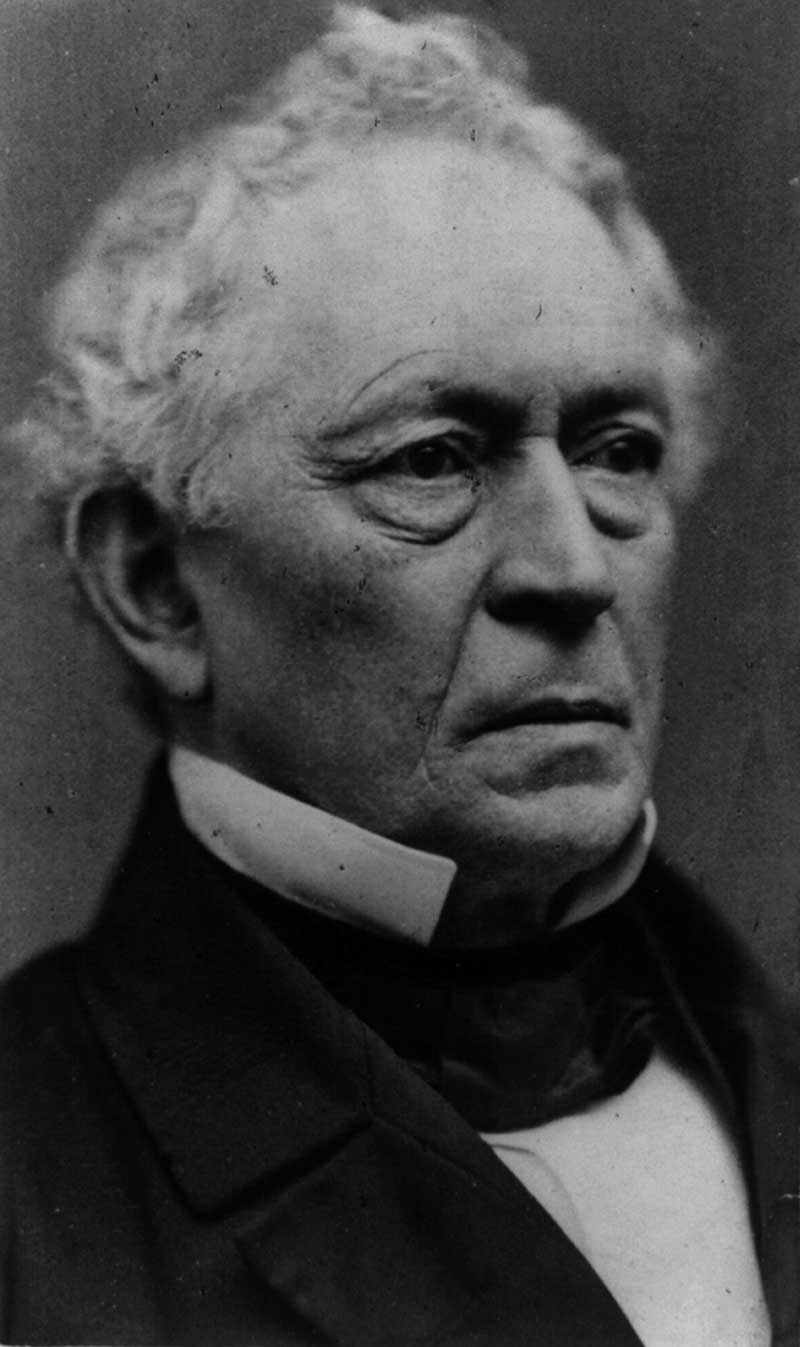

The Confederate dead were buried in long anonymous trenches, many of them retrieved by their states after the war. The Union dead were interred in a new National Cemetery, which today holds over 6,000 soldiers from the 20th Century wars as well as a few Confederates found over time buried on the battlefield. In the days following the carnage, Pennsylvania organized and appropriated funds to lay out a formal cemetery for the Union dead, and set November 19 as the day of dedication. The committee invited famous orator Edward Everett of Massachusetts and President Abraham Lincoln to give addresses. Everett spoke for two hours, rehearsing the history of the war up to the Battle of Gettysburg—a patriotic speech, and in conformity to the expectations of people who attended speeches in the 19th Century.

Edward Everett (1794-1865)

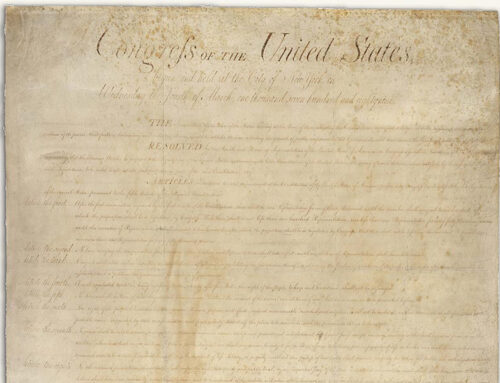

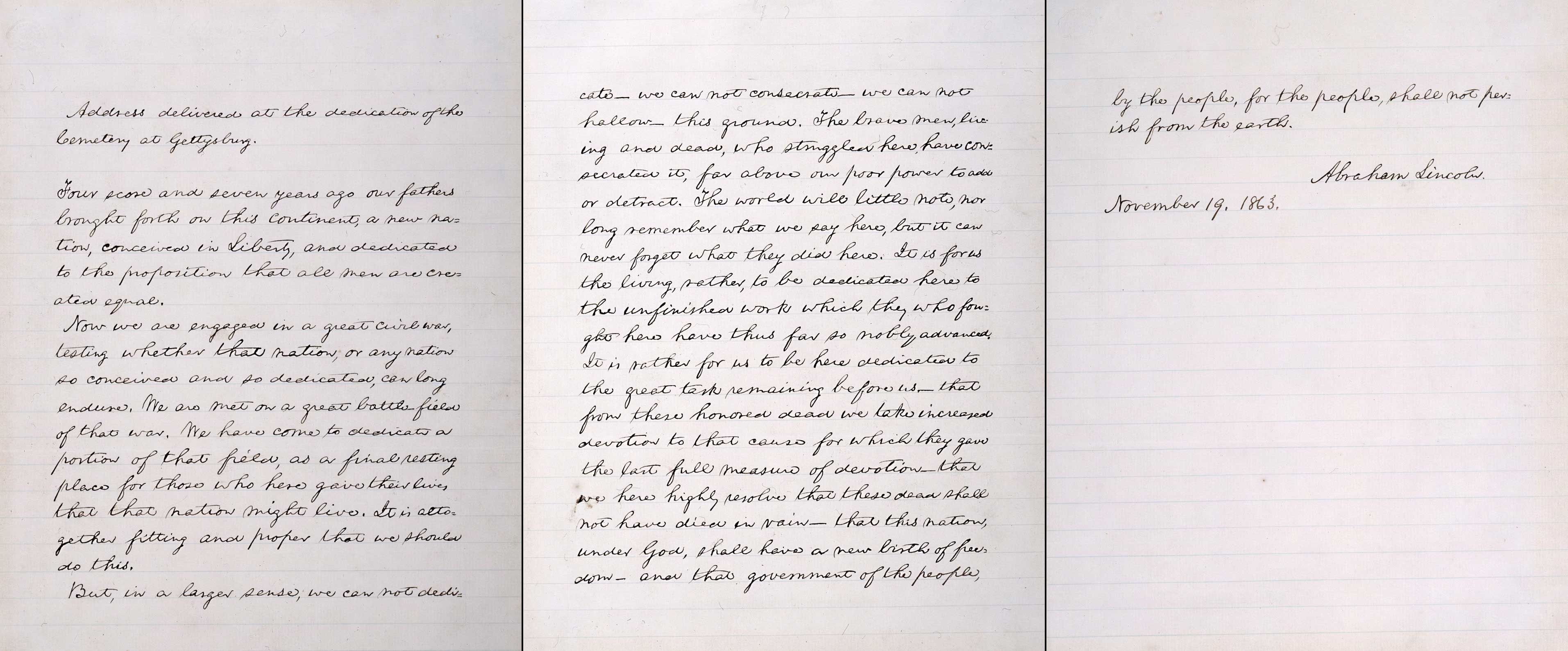

The “Bliss” copy (named for Col. Alexander Bliss, stepson of George Bancroft, the famed historian and former Secretary of the Navy), on display in the Lincoln Room of the White House

There are five known copies of the President’s two-minute-long address, in his own handwriting, each named for its recipient. The “Bliss” copy is the most often quoted, and the only one signed and dated by him. The Address has been memorized and idealized by millions of school children and adults ever since. Entire books have been written just on what is now known as “The Gettysburg Address”, which is justly considered one of the most powerful and iconic speeches of American history.

In his peroration, the Yankee President, in profound rhetorical intonations and without definition of terms, declared that the Republic’s founders believed that all men are created equal, and that the purpose of the war was to test that proposition. He further implied that the honored dead of the Union perished in an attempt to prevent the overthrow of the nation “conceived in liberty”. The President then placed on the hearers the duty to complete the salvation of the nation and give it a “new birth of freedom”. He concluded his remarks by defining the national government “of the people, by the people, and for the people”, now in danger of perishing.

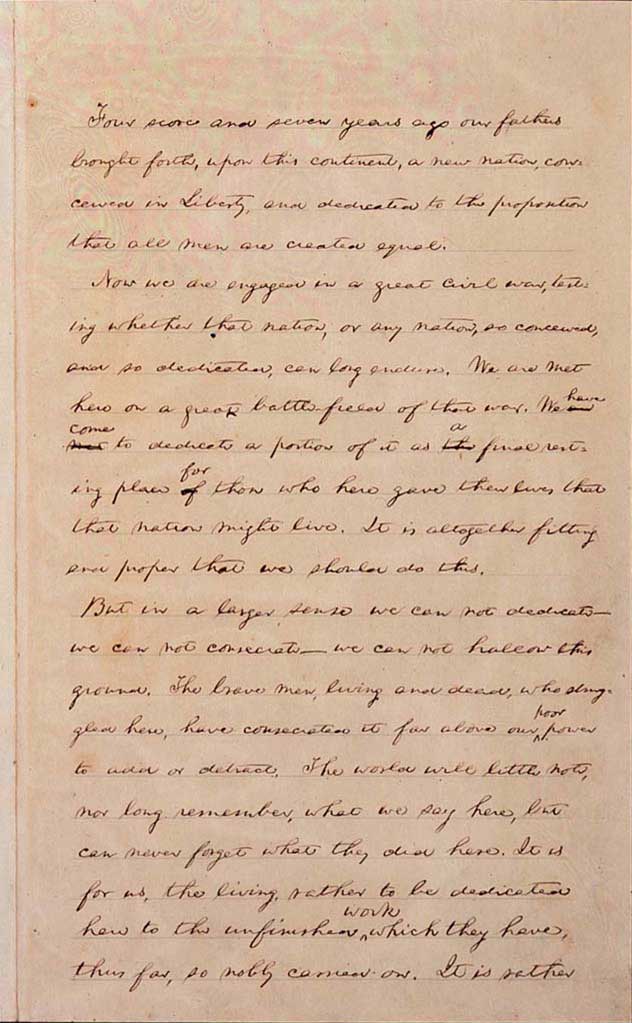

The “Hay” copy (named for John Hay, one of Lincoln’s private secretaries and custodians of Lincoln’s papers after his death), showing Lincoln’s handwritten corrections

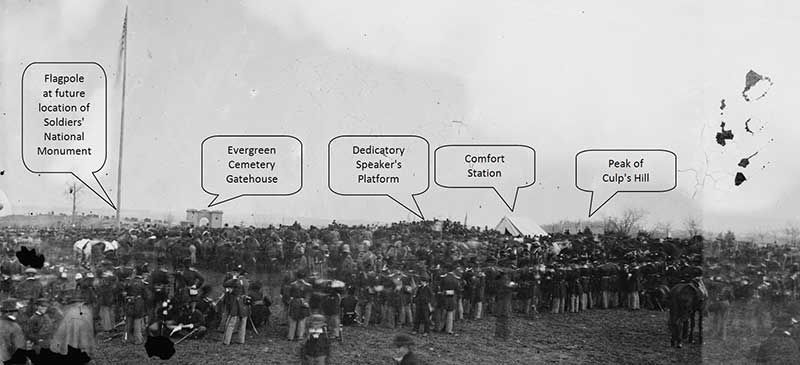

Photograph of the site of the address, taken November 19, 1863, showing the event and location of various landmarks for context

Reactions to the speech were divided along party lines. The Chicago Times described it as “silly, flat, and dishwatery”. The Springfield Republican (almost all newspapers were controlled by one party or the other), said “it was a perfect gem, deep in feeling, compact in thought and expression, tasteful and elegant in every word and comma”. In the 20th Century, journalist and professional curmudgeon, H.L. Mencken of Baltimore, weighed in against the most common understanding of what Lincoln had intoned, enraging the “Lincoln cult” even today:

“But let us not forget that it is oratory, not logic; beauty, not sense. Think of the argument in it! Put it into the cold words of everyday! The doctrine is simply this: that the Union soldiers who died at Gettysburg sacrificed their lives to the cause of self-determination—“that government of the people, by the people, for the people,” should not perish from the earth. It is difficult to imagine anything more untrue. The Union soldiers in that battle actually fought against self-determination; it was the Confederates who fought for the right of their people to govern themselves. What was the practical effect of the battle of Gettysburg? What else than the destruction of the old sovereignty of the States, i. e., of the people of the States? The Confederates went into battle an absolutely free people; they came out with their freedom subject to the supervision and vote of the rest of the country—and for nearly twenty years that vote was so effective that they enjoyed scarcely any freedom at all. Am I the first American to note the fundamental nonsensicality of the Gettysburg address? If so, I plead my aesthetic joy in it in amelioration of the sacrilege.”

H.L. Mencken (1880-1956) journalist and cultural critic who gained notoriety from his satirical reporting of the Scopes Trial, which he called the “Monkey Trial,”

Abraham Lincoln (indicated by the red arrow) amongst the crowd at Gettysburg Battlefield, taken several hours before he gave his famed address

Although he was perhaps the most unpopular President of the United States to that point in history, the immortal words of the Gettysburg Address have, regardless of one’s political or logical view of the matter, defined for generations the meaning of the Civil War and the sacrifices deemed necessary to preserve the Union.

For further study on “The Gettysburg Address”, including a comparison of the various extant copies, please consider reading this thorough overview.

Image Credits: 1 Oval Map (Wikipedia.org) 2 Gettysburg National Cemetery (Wikipedia.org) 3 Edward Everett (Wikipedia.org) 4 “Bliss” Copy (Wikipedia.org) 5 “Hay” Copy (Wikipedia.org) 6 Site of Address (Wikipedia.org) 7 HL Mencken (Wikipedia.org) 8 Lincoln at Gettysburg (Wikipedia.org)