“Let us not lose heart in doing good, for in due time we will reap if we do not grow weary.” —Galatians 6:9

The Victory of William Wilberforce, July 26, 1833

![]() rovidence is indeed inscrutable. Had Britain retained her American colonies in the late 18th Century, slavery might have been abolished in America by English Parliamentary legislation in 1833. British slave owners in the Caribbean—mainly Jamaica and Barbados—and the absentee landlords and English investors—mostly aristocrats—received compensation for their losses when England abolished slavery in the Slave Abolition Act of 1833. The act was the culmination of a lifetime of fighting for that end by a devoutly Christian Member of Parliament named William Wilberforce. He was informed of the Act three days before his own death.

rovidence is indeed inscrutable. Had Britain retained her American colonies in the late 18th Century, slavery might have been abolished in America by English Parliamentary legislation in 1833. British slave owners in the Caribbean—mainly Jamaica and Barbados—and the absentee landlords and English investors—mostly aristocrats—received compensation for their losses when England abolished slavery in the Slave Abolition Act of 1833. The act was the culmination of a lifetime of fighting for that end by a devoutly Christian Member of Parliament named William Wilberforce. He was informed of the Act three days before his own death.

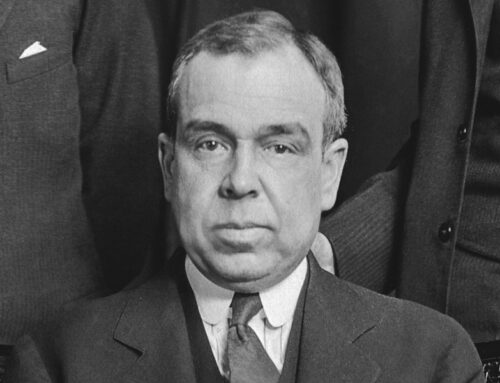

William Wilberforce (1759-1833)

Member of Parliament (1784–1812) and a leader in the slave trade abolition movement

At the age of nine, William Wilberforce began his formal schooling, falling under the influence of a godly teacher, then his aunt and uncle to whom he was sent upon the death of his father in 1767. His Methodist relatives were supporters of evangelist George Whitefield; Wilberforce became attracted to “evangelical religion.” At the age of twelve, however, William’s grandfather and mother, disturbed at his “nonconformity” brought him home to be placed under the influence of rigid Anglicanism. By the age of seventeen, Wilberforce had abandoned his attachment to evangelicalism, inherited a fortune from his grandfather, and entered Cambridge as a witty, party-loving, hail-fellow-well-met student. He excelled in his studies though rather lazy and hedonistic, earning two degrees.

The Wilberforce House in Kingston upon Hull, Yorkshire, England—birthplace of William Wilberforce

While a twenty-one-year-old college student, Wilberforce, along with his friend William Pitt, became a Member of Parliament as an independent. He continued his life as a bon-vivant, welcomed at all the best parlors and gambling dens. Although his eyesight was bad and his stature thin and small, his shrewd mind and powerful and eloquent voice won him many admirers. In 1784, on a European vacation, his life changed forever when he came to faith in Christ and submitted his life to the pursuit of godliness.

William Pitt (1759-1806) became the youngest Prime Minister of Great Britain in 1783 at the age of 24

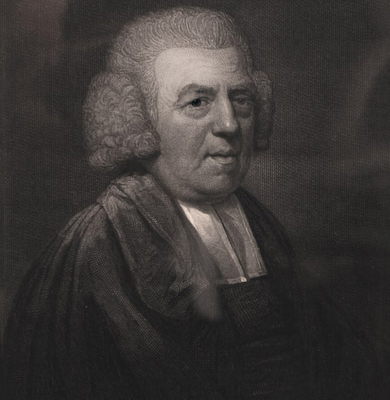

Because outspoken Christian views and evangelistic zeal were frowned on by the upper classes as boring and socially unacceptable, Wilberforce considered leaving politics altogether. He sought counsel from his pastoral friend John Newton and his old friend William Pitt (“the Younger”), both of whom strongly urged him to remain in Parliament and serve Christ in the highest councils of the land. He chose to remain in public life and champion biblical morality whatever the cost socially. In 1787 Wilberforce began what eventually became a crusade to end the slave trade.

John Newton (1725-1807), former slaver turned abolitionist who encouraged Wilberforce to stay in Parliament and “serve God where he was”

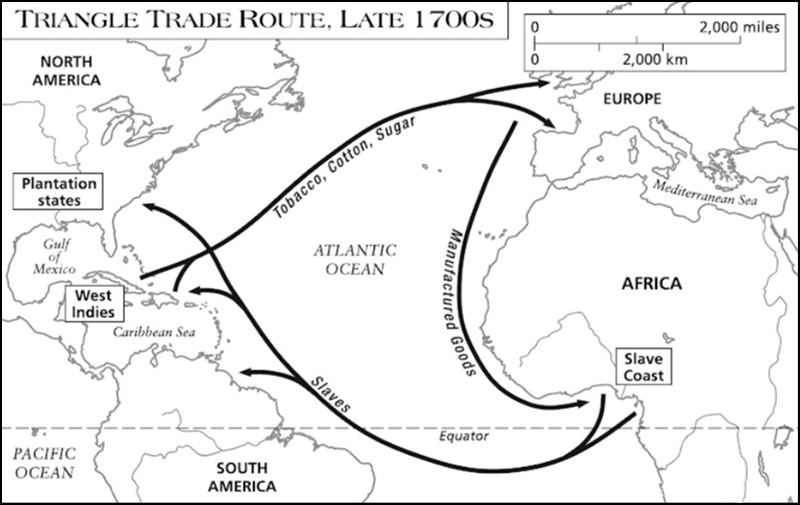

As one of the leading slave-trading nations, England’s participation garnered great wealth for the owners of the slave ships and the end-users in the Caribbean. The sugar industry in particular was utterly dependent on the trade, and made millions for the owners and shippers. The human cost in the deaths of slaves during transportation was enormous, not to mention the heavy labor in the cane fields upon arrival in Jamaica, Barbados or other of the Crown Colonies of the New World. Taking on the super-wealthy merchants and their backers in Parliament was both daunting and discouraging for reformers. Wilberforce entered in his journal that “God Almighty has set before me two great objects, the suppression of the slave trade and the reformation of manners (morals).”

Late 18th century slave trade routes

Wilberforce joined with Quakers and other fellow Anglicans in a campaign to inform the public about the horrors of the slave trade. His leadership of a remarkable fraternity, unique in British history, led to the formation of chapters of the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade all over Britain. They garnered hundreds of thousands of signatures for legislation relating to the abolition of the slave trade, and they coordinated their activities with like-minded groups in the other slave-shipping countries of Europe and the United States. Wilberforce commenced his anti-slave trade campaign in Parliament, in earnest, in 1789. In the 1790s, the French Revolution and the slave revolt in Haiti set back the forces of the anti-slave trade in England. The bills brought forth by Wilberforce were defeated again and again, and he was even accused of sympathies to the French. Undaunted, Wilberforce and his allies, now called the Clapham Sect, continued to meet, strategize and inform people, despite the criticism and success of their opponents. The parliamentary agreement to abolish the trade “gradually over time” and the War with France that broke out in 1795, slowed the cause for more than ten years.

The Battle of Vertiéres (1803)

The last major battle of the Haitian Revolution (1791-1804) a slave insurrection against French colonial rule in what is now Haiti

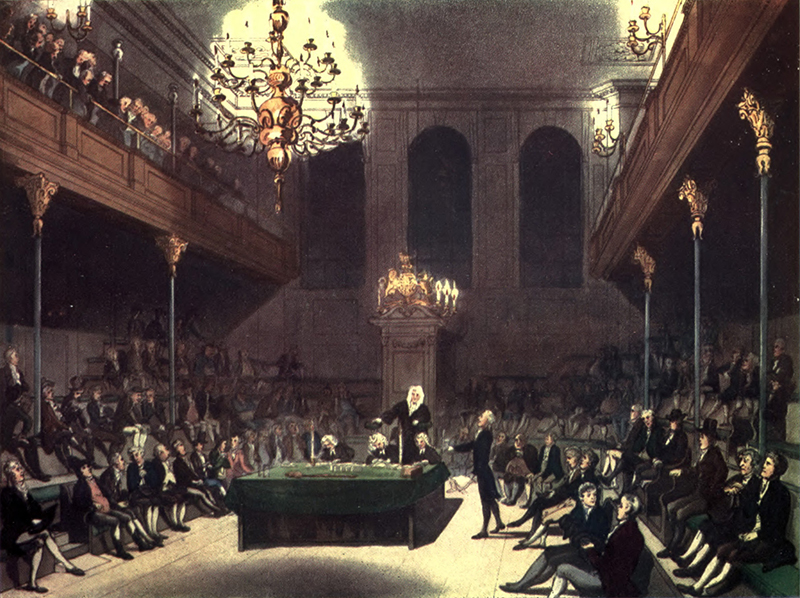

A typical scene at the House of Commons in Wilberforce’s day

The final phase of the campaign included a 400-page book by Wilberforce, and the building of a political coalition that finally ended in the abolition of the slave trade, with royal assent, in 1807, one year before the American Congress did the same. From 1812 to 1824, Wilberforce’s health deteriorated badly, but he kept up his proposals, now to end slavery altogether in the British Empire. The government was opposed to abolition of slavery itself, for it generated great wealth, especially for the vested interests of the aristocracy in the House of Lords. In his 60s, Wilberforce became the figurehead of abolitionism, having to leave Parliament with broken health. As he lay dying of the flu in 1833, he was informed that the government had finally agreed to the compromise that led to the full abolition of slavery in a bill the following year. William Wilberforce died knowing that his unique place in Christ’s Kingdom and the life-long efforts at moral reform—especially the ending of slavery in the Empire—had not been in vain.

William Wilberforce died July 29, 1833 and was buried in Westminster Abbey, close to his friend William Pitt the Younger

Image Credits: 1 William Wilberforce 1 (Wikipedia.org) 2 Wilberforce House, Hull (Wikipedia.org) 3 William Pitt the Younger (Wikipedia.org) 4 John Newton (Wikipedia.org) 5 Triangle Trade Route, Late 1700s (Wikipedia.org) 6 Battle of Vertiéres (Wikipedia.org) 7 House of Commons (Wikipedia.org) 8 William Wilberforce 2 (ArtUK.org)