“This book of the law shall not depart from your mouth, but you shall meditate on it DAY and night, so that you may be careful to do according to all that is written in it. For then you will make your way prosperous, and then you will have success.” —Joshua 1:8

John Day the Printer Dies, July 23, 1584

hen most people think about the Protestant Reformation, they think of Martin Luther and John Calvin, or other Reformers, or their aristocratic benefactors who enabled the preaching of the Gospel, with great blessing from God. There weren’t nearly enough preachers, however, to reach the millions who came in contact with the Reformation and the Bible in the vernacular of their respective countries—Germany, Holland, France, Hungary or England. The unsung heroes of the Reformation were the merchants who carried the Bibles, sermons, Psalters and other biblically orthodox religious books across Europe. They hid the books and tracts in their shipping boxes and horse-carts, their backpacks and their ships. Even more important, were the underground printers who used the new means of publishing books on a large scale, illegally, and to their own punishment if caught. The best and boldest of the lot in England was John Day.

hen most people think about the Protestant Reformation, they think of Martin Luther and John Calvin, or other Reformers, or their aristocratic benefactors who enabled the preaching of the Gospel, with great blessing from God. There weren’t nearly enough preachers, however, to reach the millions who came in contact with the Reformation and the Bible in the vernacular of their respective countries—Germany, Holland, France, Hungary or England. The unsung heroes of the Reformation were the merchants who carried the Bibles, sermons, Psalters and other biblically orthodox religious books across Europe. They hid the books and tracts in their shipping boxes and horse-carts, their backpacks and their ships. Even more important, were the underground printers who used the new means of publishing books on a large scale, illegally, and to their own punishment if caught. The best and boldest of the lot in England was John Day.

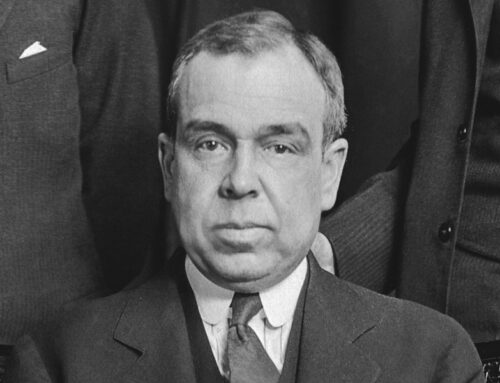

John Day (c. 1522-1584), English Protestant printer

Day was born during Henry VIII’s reign and joined the printing profession during the few years of young King Edward VI’s reign. His family origins are obscure, but his long career in printing took place in London. He likely began as an apprentice in the printing business before setting up his own presses, along with partner William Seres around 1546. Day and Seres specialized in religious books that were controversial, and received several valuable patents like Ponet’s Catechism, for popular Protestant titles. The Reformation was still in its formative years in England and there was an insatiable demand for godly literature. In the early days of their press, fully one-half of their published books attacked the superstitious doctrine of transubstantiation. They also published Continental Reformers in English. In 1549, Day and Seres amicably separated and John started his own printing presses, and joined the prestigious Stationer’s Company, a London printing guild. In 1551 he came out with a beautiful Bible, the book most in demand. His willingness to publish foreign authors, brought skilled Dutch printers to his door, men with whom he worked for the rest of his life.

King Henry VIII of England (1491-1547)

Roman Catholicism was still strong in England although the monasteries had been coopted and destroyed. The Pope had not given up on retrieving the country for the Roman Church, keeping active priests in the homes of Catholic noblemen, preparing for an opportunity to restore the Roman Church and annihilate the leading Protestants. The accession of Mary Tudor to the throne appeared to be the very opportunity to accomplish those purposes.

Devoutly Catholic, “Bloody Mary” burned at the stake for heresy some of the best-selling authors of Day and Seres; others fled to the continent, as did most printers. There is some evidence that Day remained in England and published under a pseudonym, keeping Protestant literature alive during the Marian reign. He seems to have published Lady Jane Gray and John Hooper, both martyred for their faith. Day was eventually sent to the Tower of London for “printing naughty books.” Toward the end of Mary’s reign, he was released, and worked part time with a Catholic printer, biding his time till Mary was gone.

“Bloody Mary” Tudor of England (1516-1558)

John Hooper (c. 1495-1555)

Lady Jane Grey (1537-1554)

When Elizabeth became Queen, Day was back in business printing Reformation literature, including all the sermons of the martyr Hugh Latimer, Protestant catechisms, and various works of Continental theologians, and some scientific works. The high quality of his paper, woodcuts and binding earned him a royal patent to print a particular work “for life,” securing his reputation as a master-printer. He also published Psalters, so vital to worship in all the Protestant Churches and homes, and Bible portions, affordable for the poor.

John Day’s crowning achievement, the one that secured his place in history, was the one he undertook in 1563—John Foxe’s Acts and Monuments, better known as Foxe’s Book of Martyrs. That international best-seller enabled Day to move to even larger quarters. He invested his own money in the project, and also interviewed men who had been persecuted or had known the martyrs, as he himself had. The second edition in 1570 ran to 2,300 pages in two folio volumes. William Cecil, the Queen’s main counsellor ordered every cathedral to own a copy. Collectors’ prices of the Second Edition today start at $15,000.

Queen Elizabeth I (1533-1603)

The execution of Thomas Cranmer as depicted in a woodcut from John Day’s first printing of John Foxe’s Actes and Monuments, 1563

No doubt John Day’s publishing success helped him in practical ways. His first wife bore him 13 children, as did his second wife. Puritans took the biblical injunction to be fruitful and multiply most seriously. Day seems to have had both a sense of humor (who would not with 26 children?) and a sense of the importance of the Reformation, for his printer’s device shows a rising sun and the words “Arise, For It Is Day!” The number of spiritual children that resulted from his publishing efforts, is known only to God. John Day died on July 23, 1584, probably around the age of sixty-two.

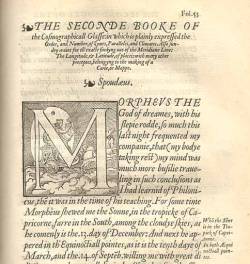

Page from John Day’s 1559 printing of William Cuningham’s Cosmographical Glasse