“Beware of false prophets, which come to you in sheep’s clothing, but inwardly they are ravening wolves.” —Matthew 7:15

Archbishop William Laud Is Executed, January 10, 1645

![]() he Archbishop of Canterbury is the highest Episcopal office in England, apart from the King or Queen, who were so designated by King Henry VIII as the “Supreme Head of the Church.” One of the most controversial and important Archbishops, William Laud (1573-1645), was executed for treason. Historian D.H. Pennington says of him:

he Archbishop of Canterbury is the highest Episcopal office in England, apart from the King or Queen, who were so designated by King Henry VIII as the “Supreme Head of the Church.” One of the most controversial and important Archbishops, William Laud (1573-1645), was executed for treason. Historian D.H. Pennington says of him:

“Laud was never much liked, even by his allies. A humourless, dwarflike figure, uninterested in court pleasures, unmarried, [likely homosexual], tactlessly impartial in his condemnations, he could never establish a party of influential supporters. During the war and interregnum, royalists and peacemakers generally preferred to forget him.”

Why should we remember him?

Archbishop of Canterbury, William Laud (1573-1645)

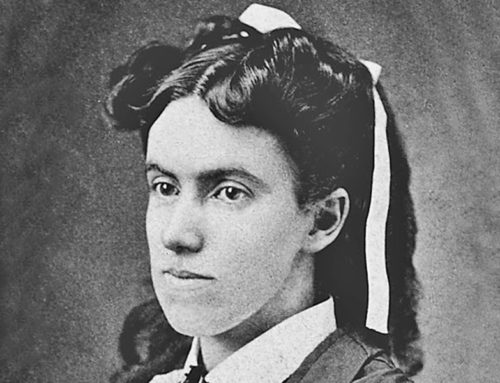

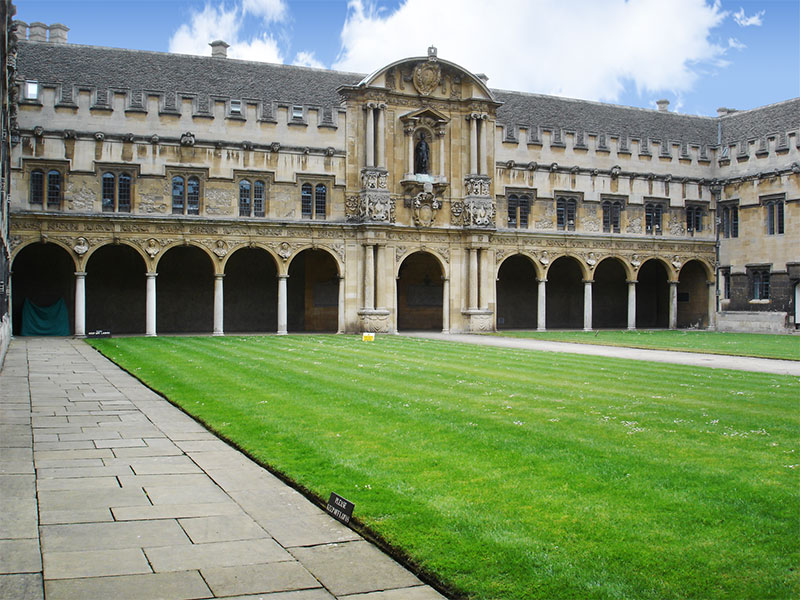

William Laud was the only son of a Berkshire clothier. He developed a love of learning at an early age and spent the rest of his life pursuing scholarship and serving as a churchman. After graduating from St. John’s College, Oxford, he began his ecclesiastical career: deacon (1601), President of St. John’s (1611), Dean of Gloucester (1616), Bishop of the see of St. David’s, 1621 (a lowly appointment since King James considered Laud a troublemaker), Dean of the Chapel Royal (1626), Privy Councilor (1627), Bishop of London (1628), and, of course, a member of the House of Lords in Parliament. The résumé seems like a typical pedestrian rise through the hierarchy of the Church of England. Much depended upon favoritism shown by various leading noblemen and the approval of the Crown, as well as the ability to politically outflank his opponents and competitors. Laud’s attachment to Thomas Wentworth, the Earl of Strafford, took on especial importance into the reign of King Charles I. What really set William Laud apart from many others was his theological attachment to Arminianism, high church outlook, and adamant opposition to the Puritans, who were still seeking to purify the church of non-biblical ceremonies and superstition.

St. John’s College, Oxford

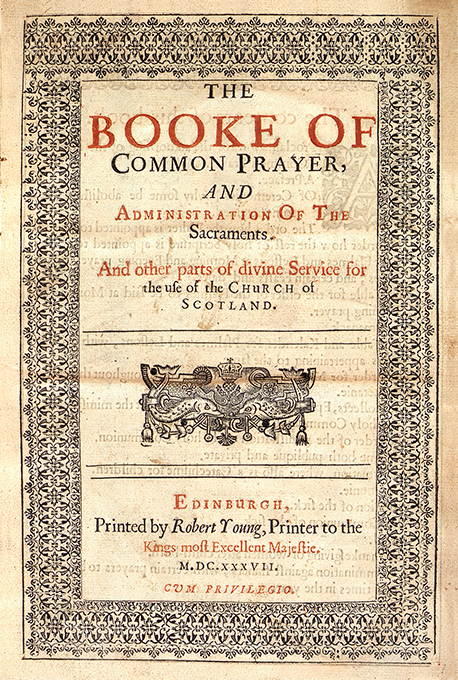

Title page from a 1637 copy of The Book of Common Prayer

King Charles I of England (1600-1649)

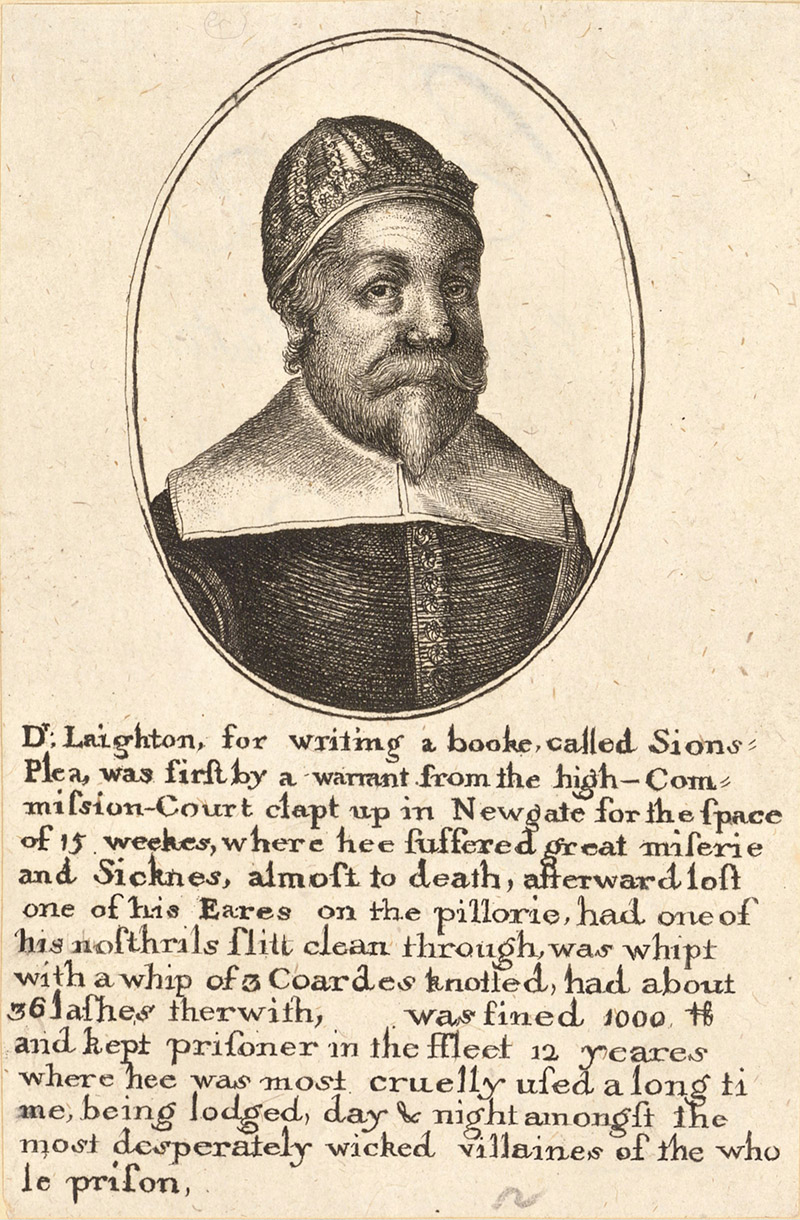

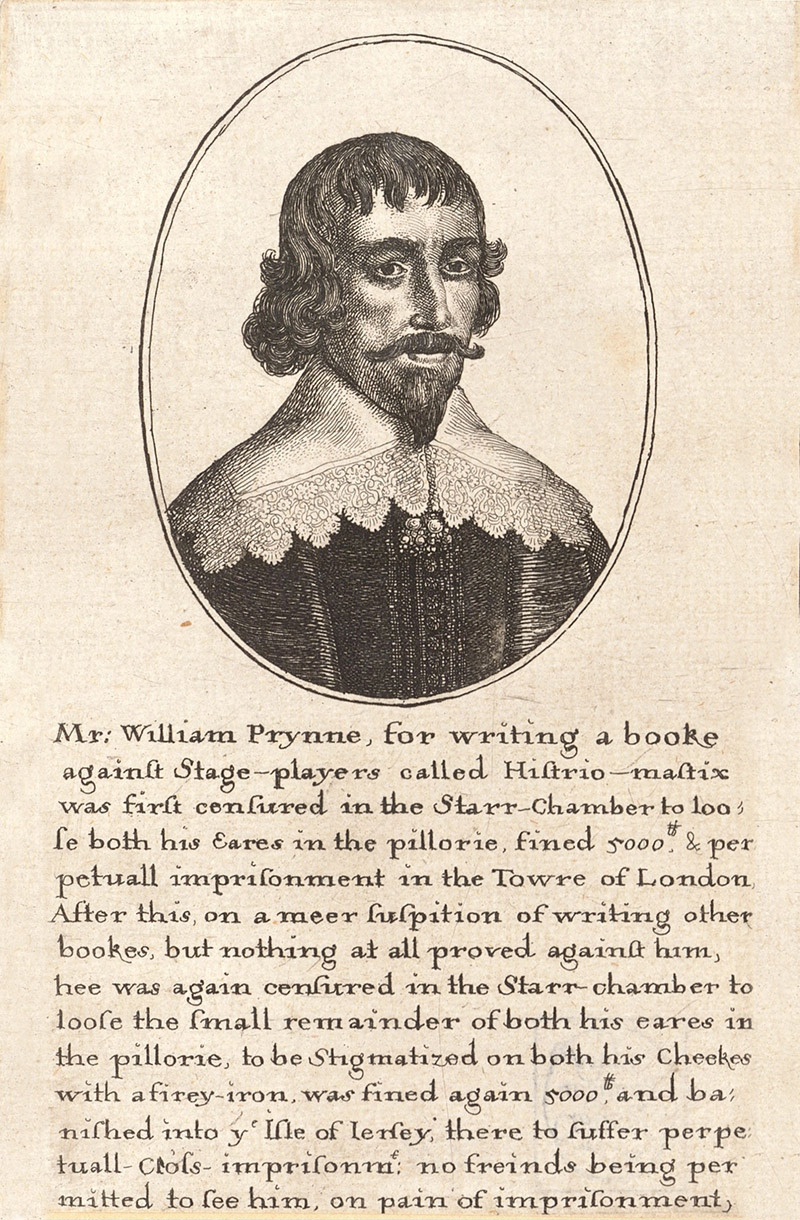

Laud incrementally sought to return the church to rites and beliefs reminiscent of its Roman Catholic past. He demanded adherence to external aspects of worship like strict use of The Book of Common Prayer, wearing the surplice, bowing at the name of Jesus, consecrating churches, etc. In 1633 he was appointed Archbishop of Canterbury by Charles I, a position from which he could extend his persecution of Puritans across England and Scotland. He suppressed Puritan books and tracts, arrested what he called “propagandists,” Alexander Leighton and William Prynne and had them mutilated and thrown in prison; he rejected any changes proposed by Puritans. Though short in stature, William Laud loomed large in the Church of England to remake it away from the Reformation.

Laud was especially opposed to the Puritan emphasis on preaching and tried to curtail it wherever possible. It militated against his desire to amalgamate church and state and led to sedition. Laud worked hard to place bishops and clergy sympathetic to his ideas and plans in as many churches as possible, though he met constant resistance from the more Reformed elements of the English Church. The popular support for the Puritan cause was much larger than those who agreed with Laud. The more action he took against them, the more the rebellion against his policies.

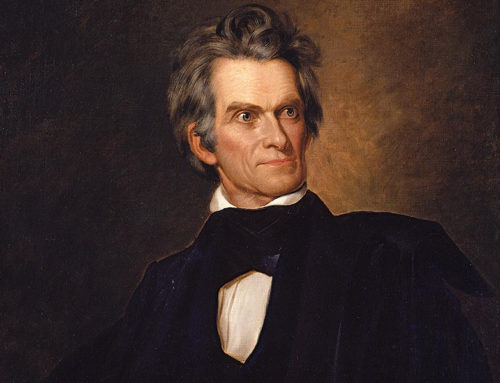

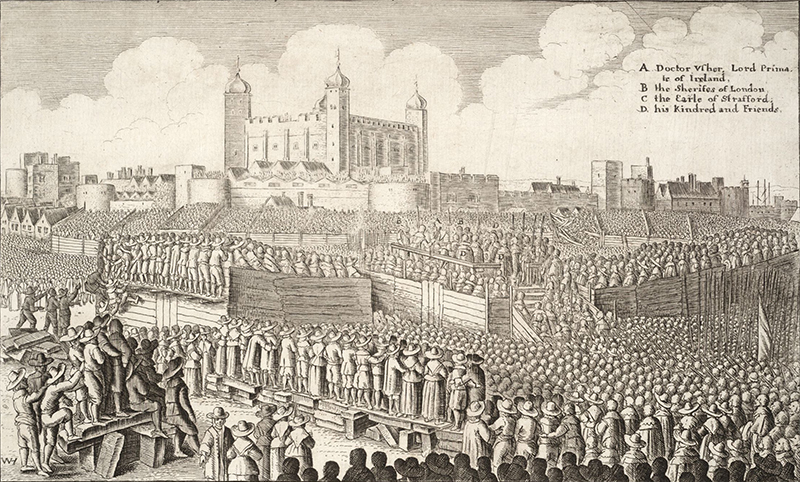

In 1639 King Charles went to war with Scotland over these very issues. They had rejected and sacked his bishops and declared Christ the Head of the Church, separating the State from the Church. He called Parliament into session for the first time in eleven years, to raise money for war, but they refused. They were dissolved after convening for only three weeks. A few months later, Charles again called Parliament together, seeking money after the disastrous “Bishop’s War” with Scotland. This time they would not be dissolved by the King. The MPs demanded the arrest of the Earl of Strafford and of his close ally and supporter William Laud, Archbishop of Canterbury. Both were impeached for High Treason. Strafford was beheaded shortly thereafter. Laud suffered the same fate four years later, after languishing in the Tower of London. In both cases it proved difficult to prove treason; a bill of attainder from Parliament resulted in their conviction and execution. Historians have not been particularly kind to the Archbishop “a ridiculous old bigot,” (Macaulay). As one royal wit said “Give praise to the Lord, and little Laud to the devil.”

Thomas Wentworth, 1st Earl of Strafford (1593-1641)

The execution of Thomas Wentworth, 1st Earl of Stafford, May 12, 1641, was by some estimates attended by as many as 300,000

He had been integral in trying to roll back the Reformation and impose an Anglo-Catholicism on England and Scotland. The resulting Bishop’s Wars and the English Civil Wars resulted from his and the inept King’s policies. Had Laud reinforced the Calvinistic Puritan movement and not pursued belligerent schemes to return the Church in a papal direction, there may never have been a Cromwell in England or Covenanters in Scotland — but then such speculation is unsafely questioning Providence.

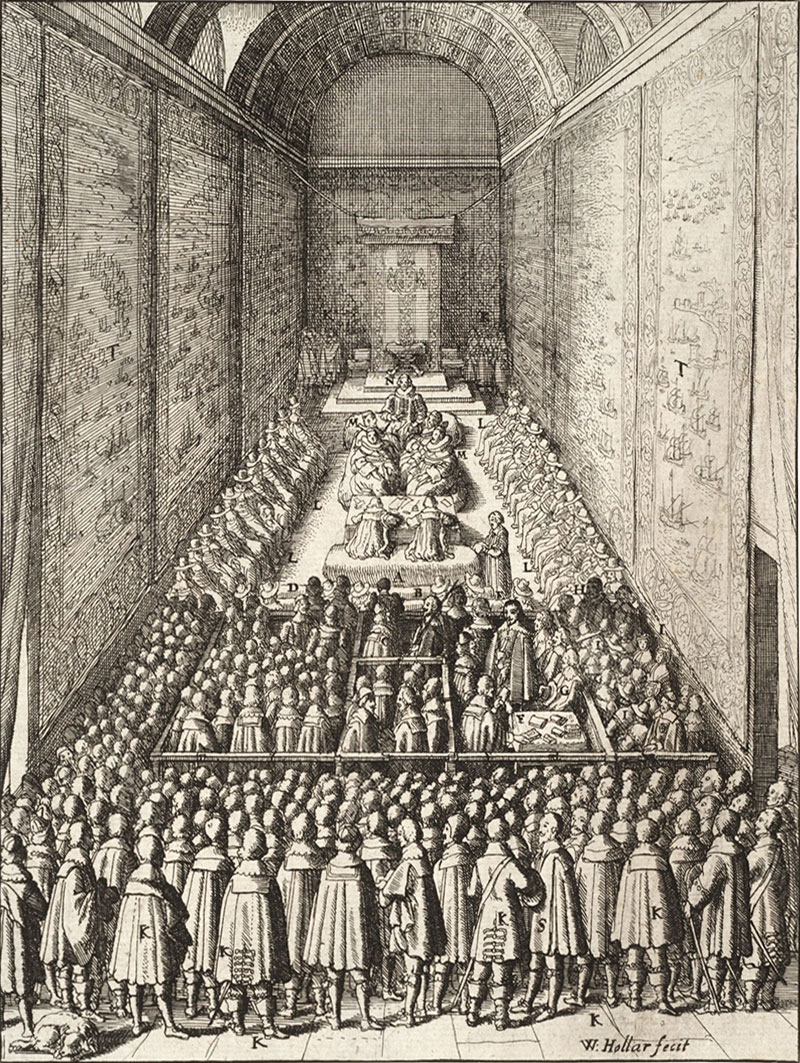

The trial of Archbishop Laud (above) ended without a verdict, having proved impossible to identify any specific act of treason. Parliament eventually passed a bill of attainder under which he was beheaded on January 10, 1645 on Tower Hill, despite being granted a royal pardon

Image Credits: 1 William Laud (Wikipedia.org) 2 St. John’s College (Wikipedia.org) 3 1637 Book of Common Prayer (Wikipedia.org) 4 King Charles I (Wikipedia.org) 5 Alexander Leighton (Wikipedia.org) 6 William Prynne (Wikipedia.org) 7 Earl of Strafford (Wikipedia.org) 8 Execution of Strafford (Wikipedia.org) 9 Trial of William Laud (Wikipedia.org)