“He hath showed thee O man, what is good; and what doth the Lord require of thee, but to do justly, and to love mercy, and to walk humbly with thy God?” —Micah 5:8

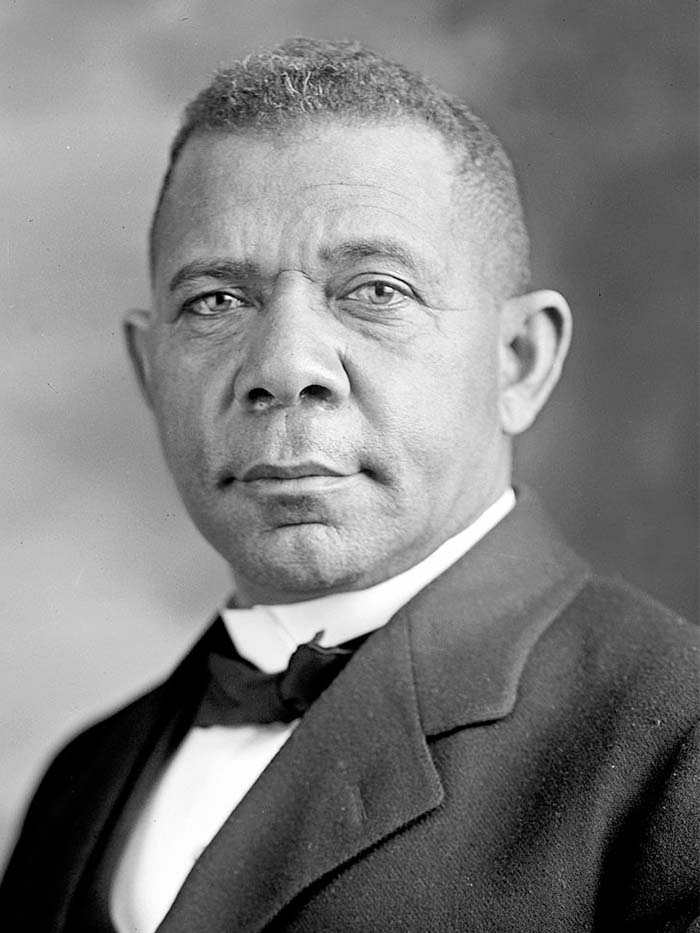

Birth of Booker T. Washington

April 5, 1856

![]() he 1860 census taker noted that the Burroughs family in Franklin County, Virginia and their fourteen children, also had seven slaves, one of them a boy named Booker, valued at $400.00. Born to Jane, a slave, father unknown but to the mother, Booker’s prospects in life could not have been fewer nor more dismal. In 1865, at the age of nine, however, he and his mother found themselves free and allowed to leave for a different life. She took Booker to West Virginia to reunite with her husband, Washington Ferguson, working in the coalfields. Booker found out his middle name was Talliaferro, which he usually shortened to “T” and adopted Washington as his surname. Providence declared that his life would not be one lived in a colliery.

he 1860 census taker noted that the Burroughs family in Franklin County, Virginia and their fourteen children, also had seven slaves, one of them a boy named Booker, valued at $400.00. Born to Jane, a slave, father unknown but to the mother, Booker’s prospects in life could not have been fewer nor more dismal. In 1865, at the age of nine, however, he and his mother found themselves free and allowed to leave for a different life. She took Booker to West Virginia to reunite with her husband, Washington Ferguson, working in the coalfields. Booker found out his middle name was Talliaferro, which he usually shortened to “T” and adopted Washington as his surname. Providence declared that his life would not be one lived in a colliery.

Booker T. Washington (1856-1915)

Though living in a shantytown hovel, he learned to read and write while attending a “Negro school” taught by a literate black Union veteran. Reading opened the whole world to Booker T. Washington and he gloried in learning. Toiling in the mines, he heard of a college for young men like himself — Hampton Institute in Hampton, Virginia. Through donations by older black men and through his own savings, he travelled there for a visit. Accepted as a student, Booker had to learn some of the most basic activities of an ordered life and to live by a highly regimented schedule. At Hampton, Booker “drank deeply” from the teachings of the founder, General Samuel Chapman Armstrong, the son of missionaries to Hawaii. The Christian educators of the Institute taught him the Holy Scriptures, self-discipline, and the value of hard work as a God-ordained purpose. Graduating in 1875, Booker T. Washington was ready to put into practice his life principles.

Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute, Hampton, Virginia, circa 1896

His speech to the graduating class at Hampton Institute a few years later revealed the philosophy that would guide his teaching and actions on behalf of black Americans for the rest of his life:

“There is a force with which we can labor and succeed and there is a force with which we can labor and fail. It requires not education merely, but also wisdom and common sense, a heart bent on the right and trust in God . . . There is a tide in the affairs of men . . . [quoting Shakespeare] not in planning but in doing, not in talking noble deeds, but in doing noble deeds.”

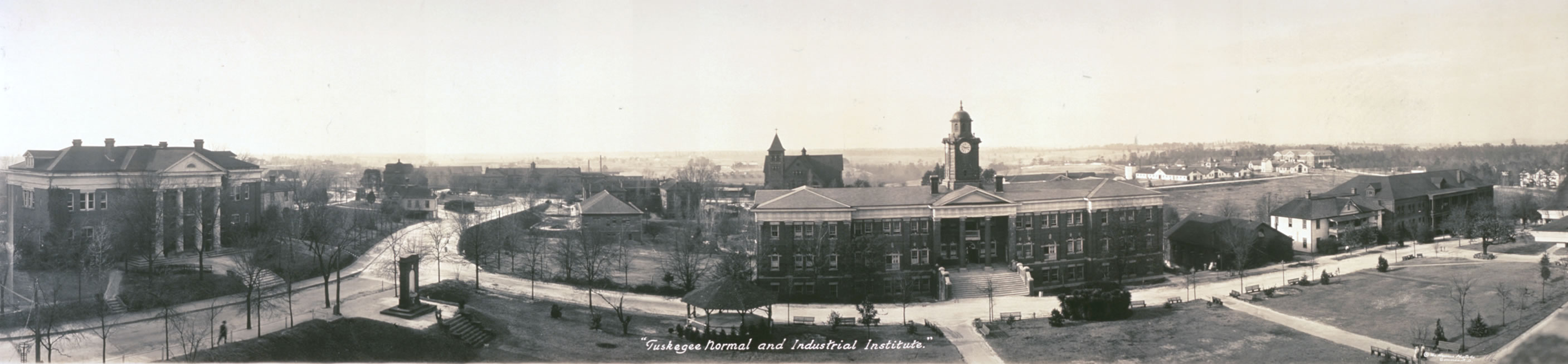

Tuskegee Institute, circa 1916

Booker T. Washington is remembered for many accomplishments, although two have stood out to historians since that time: his founding of the Tuskeegee Institute and its great success in educating many of the post-slavery generations of black Americans in the South, and his famous speech at the Atlanta Expo in 1895, euphemistically called the Atlanta compromise. Through his eloquence, arguments, and Christian character, Washington was able to acquire funding from a number of philanthropists, who enabled him to fulfill his dream of a college to educate black Americans of the rural South. The instructors at Tuskeegee taught the students how to acquire the critical skills for jobs open to them, and to excel in all they pursued. He thought strategically about how to get along in a culture that still put social, political, and economic barriers in front of black Americans. Washington became the most prominent spokesman for the former slaves and their descendants, by the end of the century.

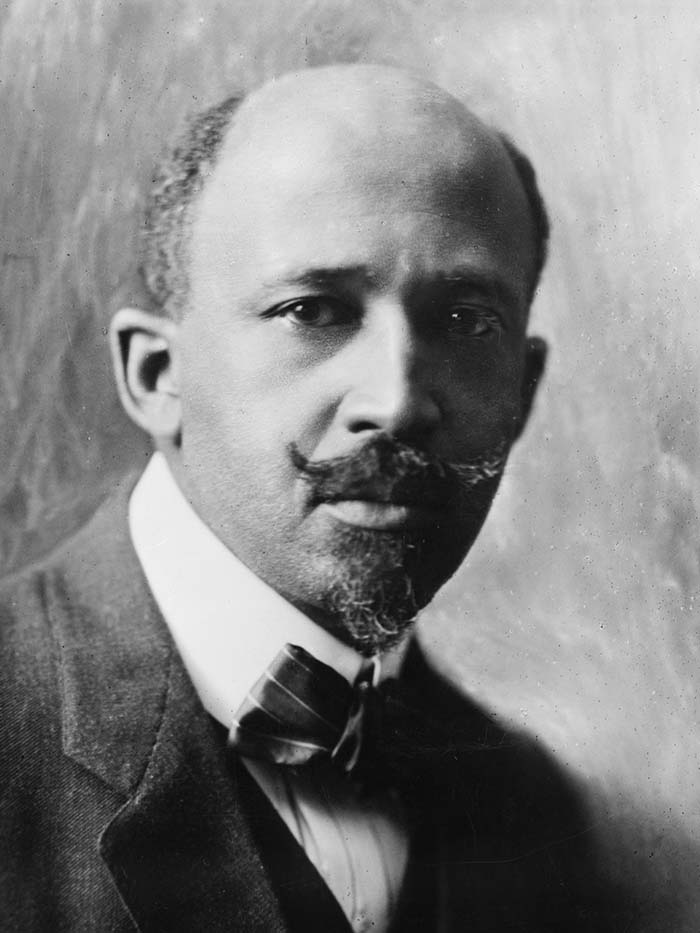

William Edward Burghardt (W.E.B.) Du Bois (1868-1963)

In the early 20th Century, Dr. W.E.B. Dubois, Massachusetts-born and educated black intellectual, prolific author, socialist leader, historian, civil rights activist, co-founder of the NAACP and leader of the pan-African movement also rose to prominence as a spokesman for black interests. He contended with Washington over the goals and means of elevating the fortunes of black Americans. Washington quietly helped subsidize strategies for voting rights and defeating Jim Crow laws but preached and taught hard work and self-sufficiency at the same time. DuBois publicly attacked the ideas and practices of Capitalism, Colonialism, and racial prejudice wherever he found them, and agitated for radical reform. The solidly Republican Booker Washington, visited the White House of Theodore Roosevelt and William Taft and consulted with the Presidents on race issues. The contrast in message and style between Washington and DuBois has often been remarked upon by historians and has remained contentious since then. Booker T. Washington died at the age of 59 in 1915, his chief rival lived until 1963 and died in Africa at the age of 95. Roosevelt said of Booker T. Washington that he “combined the traits of humility and dignity . . . which were the outward expressions of the spiritual fact that he . . . walked humbly with his God.”

Booker T. Washington and Theodore Roosevelt at Tuskegee Institute, 1905