“Iron sharpens iron, and one man sharpens another.” —Prov. 27:17

“Two are better than one, because they have a good reward for their toil.” —Ecc. 4:9

The Death of John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, July 4, 1826

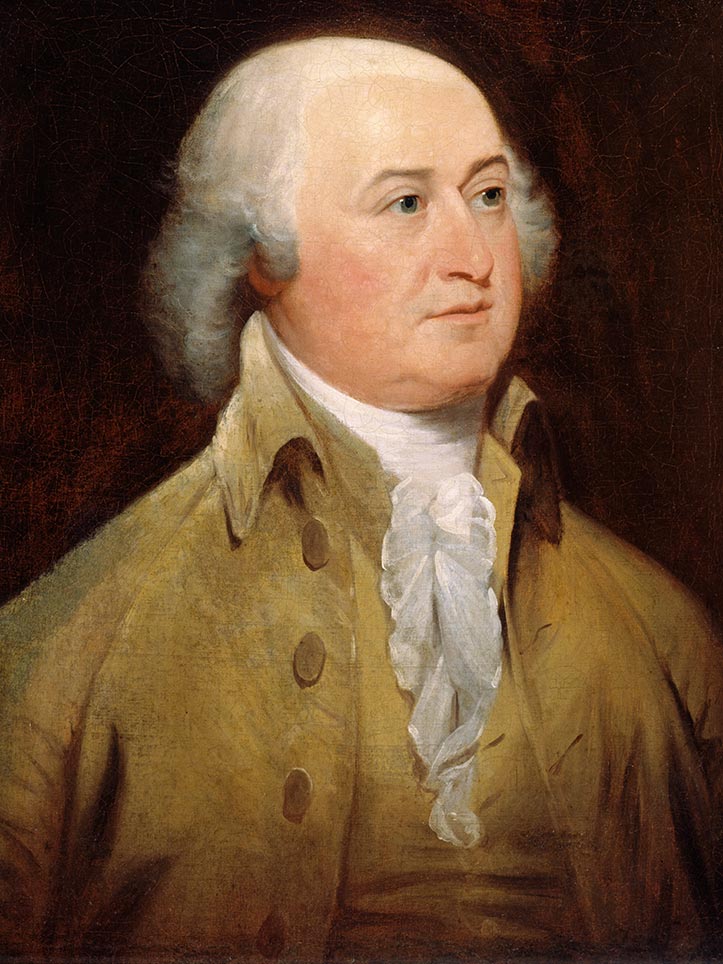

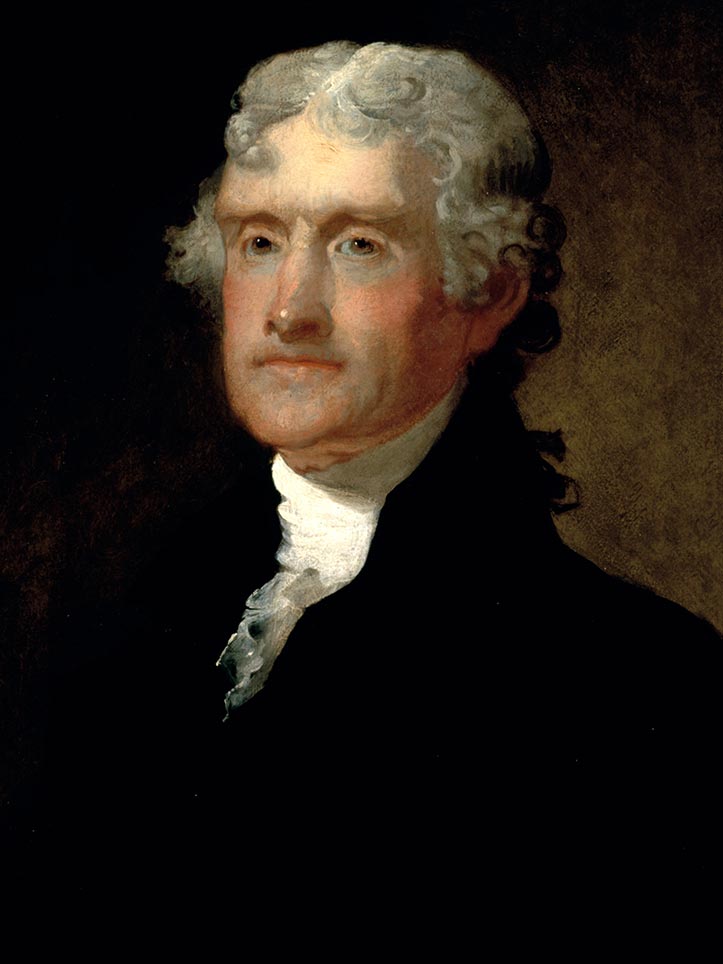

![]() hey could hardly have been more unlike in appearance and character. Adams was older — short, rotund, sometimes irascible, but “humane, generous and open,” with “a keen sense of humor, an eye for the ridiculous and incongruous, and a willingness to poke fun at himself.” Loyalist Jonathan Sewell said that the Massachusetts firebrand John Adams had a “heart formed for friendship.” A quiet Virginian, Thomas Jefferson was tall and angular, red-headed, modest and courtly. He never gave public speeches and kept a private and reserved demeanor outside his domestic environment. In heated debates, he kept his own counsel while his bombastic New England friend expostulated with drama. Yet they were the men paired by their peers in the Continental Congress to author the Declaration of Independence in 1776. As a mysterious diktat of Providence, they both died on the day of jubilee of that historic document, in 1826. The story of their friendship is one of the most remarkable in American history.

hey could hardly have been more unlike in appearance and character. Adams was older — short, rotund, sometimes irascible, but “humane, generous and open,” with “a keen sense of humor, an eye for the ridiculous and incongruous, and a willingness to poke fun at himself.” Loyalist Jonathan Sewell said that the Massachusetts firebrand John Adams had a “heart formed for friendship.” A quiet Virginian, Thomas Jefferson was tall and angular, red-headed, modest and courtly. He never gave public speeches and kept a private and reserved demeanor outside his domestic environment. In heated debates, he kept his own counsel while his bombastic New England friend expostulated with drama. Yet they were the men paired by their peers in the Continental Congress to author the Declaration of Independence in 1776. As a mysterious diktat of Providence, they both died on the day of jubilee of that historic document, in 1826. The story of their friendship is one of the most remarkable in American history.

John Adams (1735-1826)

Portrait by John Trumball, 1793

Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826)

Portrait by Mather Brown, 1786

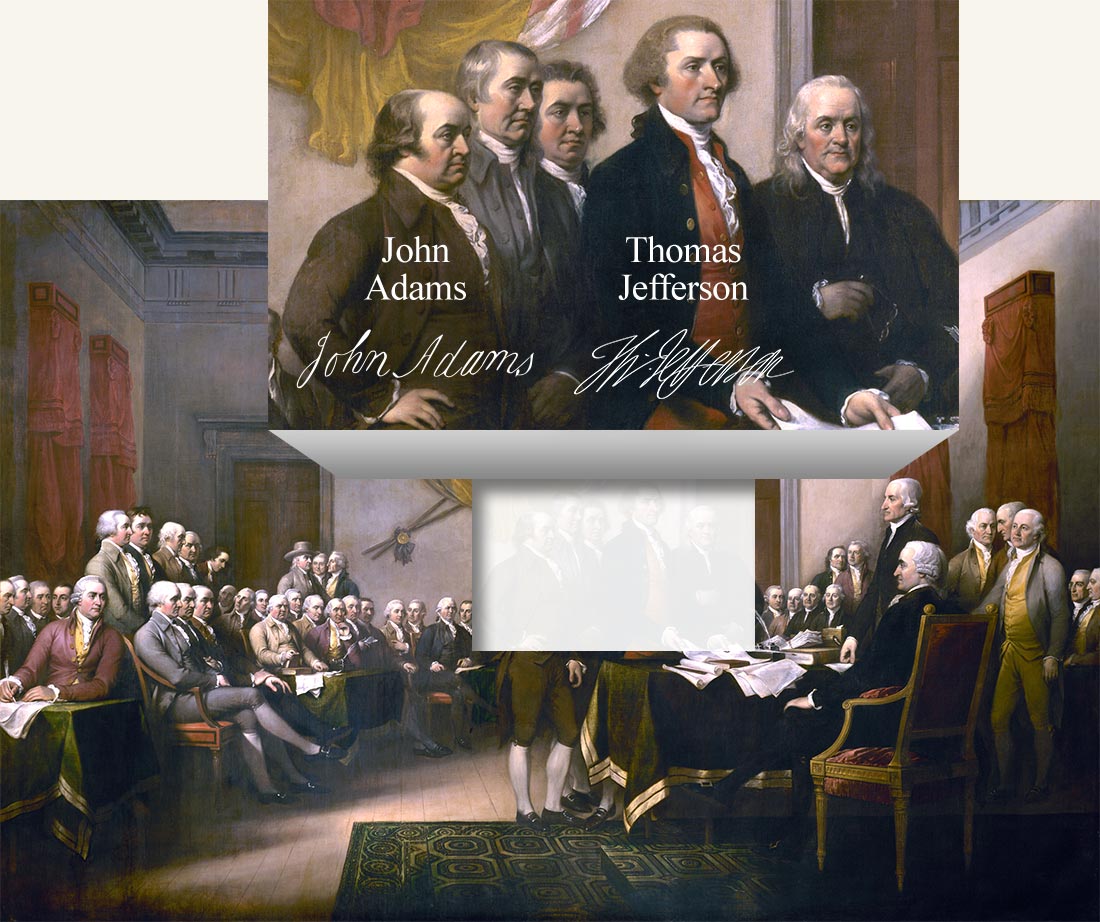

Thrown together at the Continental Congress, Adams and Jefferson impressed their fellow delegates in different ways but their devotion to the cause was such that they were both placed on the committee to write the Declaration. Their friendship matured, however, when both were sent to France, along with Benjamin Franklin, to woo the French government into officially recognizing the United States and provide support in loans and troops. The two men’s passion for liberty under law and willingness to sacrifice their “lives, their fortunes, and their sacred honor” in the cause of independence was not all that they had in common, however. They were both men of the soil and loved their farms and their families. Both of their wives bore six children, though Jefferson’s Martha died at the age of thirty-three in 1782 and Abigail Adams lived till 1818 and the age of seventy three.

Declaration of Independence, by John Trumball depicts the five-man drafting committee — including John Adams and Thomas Jefferson — presenting their work to Congress

The two great founders parted ways when their political views diverged as they served in the Washington administration in the last decade of the 18th Century. As one historian began his account of the “tumultuous election of 1800,” Adams and Jefferson could “write like angels and scheme like demons.” Their correspondence and friendship came to end in that bitter “first true presidential campaign.” Adams had always been more favorable to England and Jefferson’s love of France and support of the French Revolution had initially proven a point of contention. The 1800 election highlighted the discordant ideals of the two friends — Jefferson’s ardent republicanism and Adams’s federalism. Apart from a few perfunctory letters between Abigail Adams and Jefferson, the principle founders remained aloof from each other for a number of years.

John Adams age 88 in 1823 —

Portrait by Gilbert Stuart made at the request of Adams’s son, John Quincy

Thomas Jefferson age 78 in 1821 —

Portrait by Matthew Harris Jouett

In 1812, mutual friends gave them occasion to reignite their friendship and it continued unabated till their death on the same day in 1826. The “practical idealist” and the “skeptical realist” both understood their vital roles in creating the Republic and went to their deaths with the other man in their thoughts. Providence has occasionally brought together men whose friendship defined the path of the future.