“Jesus answered, My kingdom is not of this world: if my kingdom were of this world, then would my servants fight, that I should not be delivered to the Jews: but now is my kingdom not from hence.” —John 18:36

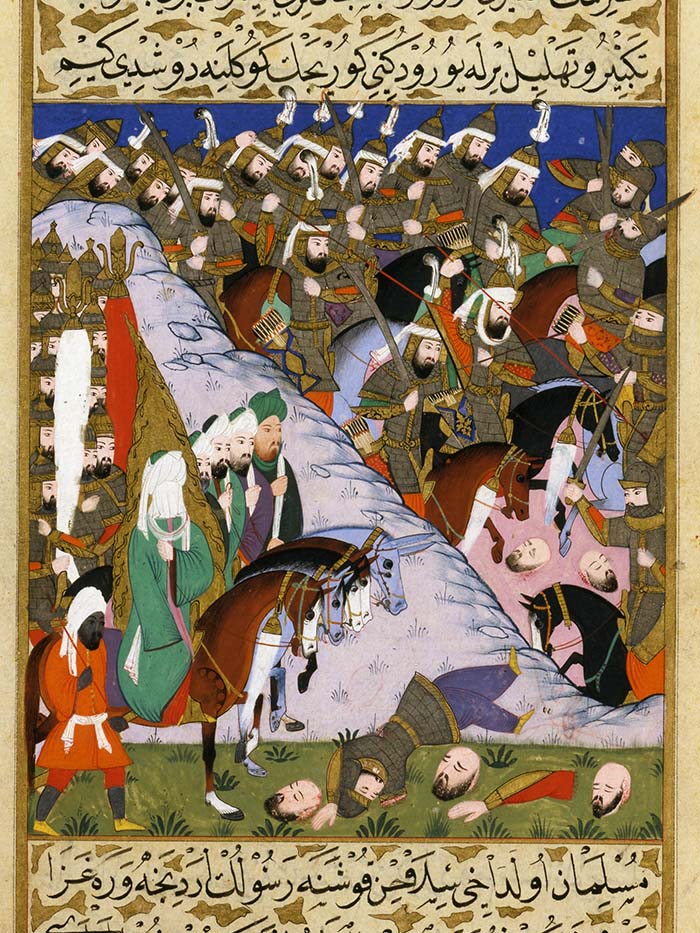

Saracens Attack after First Crusade,

March 9, 1144

eus Vult! The battle cry of the Crusaders, “God Wills It,” is no longer heard outside the walls of Accra, Antioch, Jerusalem and all the other Christian strong-points in the Levant. Allahu Akbar, however, has lost none of its caché. Few events in Medieval and church history elicit more condemnation and revulsion than the Crusades of the 11th and 12th centuries. Critics of medieval Christianity constantly cite the Crusades to explain and excuse Muslim attacks on the West in current times. What caused thousands of Christian knights and tens of thousands of regular people to drop everything and trudge almost three thousand miles facing starvation, disease, and massacre, to fight the Islamic armies in the Middle East? Why would the most prominent leaders of the Christian Church urge such wars, and even offer indulgences for those who would join the Crusaders? The answers, as usual, are more complicated than we are often led to believe, or can explain fully in a brief account.

eus Vult! The battle cry of the Crusaders, “God Wills It,” is no longer heard outside the walls of Accra, Antioch, Jerusalem and all the other Christian strong-points in the Levant. Allahu Akbar, however, has lost none of its caché. Few events in Medieval and church history elicit more condemnation and revulsion than the Crusades of the 11th and 12th centuries. Critics of medieval Christianity constantly cite the Crusades to explain and excuse Muslim attacks on the West in current times. What caused thousands of Christian knights and tens of thousands of regular people to drop everything and trudge almost three thousand miles facing starvation, disease, and massacre, to fight the Islamic armies in the Middle East? Why would the most prominent leaders of the Christian Church urge such wars, and even offer indulgences for those who would join the Crusaders? The answers, as usual, are more complicated than we are often led to believe, or can explain fully in a brief account.

Mohammed, leading his followers into battle

Pope Urban II

Although Mohammed, the creator and prophet of Islam, died in A.D. 632, he left behind the Koran and his own example for his converts to follow. The commandment to wage continuous and unabated holy war or “jihad” against the enemies of Allah, the god of Islam, spurred the Arab tribes to new heights of conquest. The unrelenting wars against Christendom, Jews, and the various fellow pagans of Arabia and elsewhere, lasted for more than a thousand years. Successes were followed by the establishment of Sharia Law in the conquered nations. Within their first century, the followers of Islam stretched from the borders of China to the southern borders of France and over all of North Africa and the Middle East. At the Battle of Tours in France in 732, Charles “The Hammer” Martel finally stopped the Muslim horde and drove them back over the Pyrenees. There were some within Christendom, including several popes, who began advocating a Christian military response in kind. In 1095 they got their wish.

In 1065 seven thousand Christians were ambushed and massacred on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem. The leaders of the Eastern Church in Constantinople also asked for help. Pope Urban II convinced famous preachers like Bernard of Clairveaux to promote a crusade to liberate “The Holy Land” from Muslim domination. The retaking of Jerusalem became the raison d’ être for the recruiting of a multi-national army of western Christendom to fight the Muslims. About 130,000 people set out on the First Crusade, with about 13,000 nobles and knights, perhaps 50,000 trained infantry, 15,000 non-combatants—priests, camp-followers, and an unknown number of peasants and villagers “swept up in the excitement”.

Peter the Hermit Preaching the First Crusade, from Cassell’s History of England, Vol. I

Three primary elements were part of the First Crusade — The People’s Crusade led by Peter the Hermit and Walter the Penniless, The German Crusade led by a priest named Volkmar, and a third group usually known as the Princes’ Crusade made up of well-armed, well-trained knights. The German contingent massacred Jews along the way and in turn were themselves, annihilated in Hungary. The well-funded but almost totally undisciplined commoners of Peter’s army suffered heavy losses but the survivors made it to Constantinople, from whence they set out to loot nearby towns and were wiped out by the Turks.

Conquest of Jerusalem by Crusaders in the First Crusade, 1099

The military phase of the First Crusade found the forces of the Frankish Princes fighting their way from Constantinople to Jerusalem, winning smashing victories and establishing garrisons along the way. The enormous cost of the campaign had reduced the Crusader force to 1,300 knights and 10,000 infantry by the time they arrayed themselves before the enormous fortress walls of Jerusalem. The Muslim commander in the city refused to surrender, so the crusaders carried it by storm, putting much of the population to the sword, as was the custom of medieval warfare, and well up into the 17th Century.

Jerusalem today, showing the contrast of two worldviews

Most of the surviving knights returned home, having been gone for several years. Only three hundred knights remained behind to establish the Crusader kingdoms of Tripoli, Antioch, Edessa, and Jerusalem under Godfrey of Bouillon. The Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem lasted one hundred ninety two years. On this day in 1144, the reorganized Saracen armies swept into Syria and captured Edessa. The beginning of the end of the Crusader knights’ control of the Middle East had begun. By 1291, the entire region, but for Constantinople was again in the hands of Islam. Christendom was thrown back on defending the frontiers of their own homelands from militant Islam, and winning the hearts and minds of Muslims had returned to evangelism, suffering, and the peaceful means of Christ’s spiritual Kingdom.