“They that go down to the sea in ships, and occupy their business in great waters; These men see the works of the Lord, and his wonders in the deep. For at his word the stormy wind ariseth, which lifteth up the waves thereof. They are carried up to the heaven, and down again to the deep.” —Psalm 107:23, 24

The Sinking of the Edmund Fitzgerald,

November 10, 1975

![]() he Great Lakes contain 21% of the world’s fresh water by volume—more than 94,000 square miles of surface. Lakes Superior, Huron, Michigan, Erie and Ontario interconnect with one another and access the Atlantic Ocean via the St. Lawrence River and Seaway. They have often been called inland seas due to their rolling waves, high winds and currents, as well as ocean-like depths, not to mention about 35,000 islands. Lake Superior is the largest freshwater surface lake in the world and provides shore-line to Canada, and the states of Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Michigan. It is larger than five New England states combined and receives water from more than three hundred rivers and streams. It is known for the ferocious storms that occasionally arise on its waters.

he Great Lakes contain 21% of the world’s fresh water by volume—more than 94,000 square miles of surface. Lakes Superior, Huron, Michigan, Erie and Ontario interconnect with one another and access the Atlantic Ocean via the St. Lawrence River and Seaway. They have often been called inland seas due to their rolling waves, high winds and currents, as well as ocean-like depths, not to mention about 35,000 islands. Lake Superior is the largest freshwater surface lake in the world and provides shore-line to Canada, and the states of Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Michigan. It is larger than five New England states combined and receives water from more than three hundred rivers and streams. It is known for the ferocious storms that occasionally arise on its waters.

A 2010 satellite image of the Great Lakes region, showing Lakes Superior,

Michigan, Huron, Erie, and Ontario (L-R)

Collectively there have been more than 6,000 ships sunk in the Great Lakes, with the loss of about 20,000 lives. Three hundred fifty of those ships went down in Lake Superior. The most famous of the lost ships, immortalized in song, was the iron ore freighter Edmund Fitzgerald, which sank with all hands on November 10, 1975.

The Edmund Fitzgerald underway in 1971

The Lake Superior iron ranges supply about 85% of the iron ore demands of the United States iron and steel industry, which today makes it a two billion dollar industry. An iron ore range is an “elongate belt of sedimentary rocks in which one or more layers consists of a banded iron formation . . . on a scale of a few centimeters.” Most of the iron ranges in the three states were discovered in the 1840s and 50s, and by the 1880s were in full iron ore production. Lake Superior became the super-highway of transporting ore to the factories around the United States, from the foundries and blast furnaces of Gary, Indiana to those in Elyria, Cleveland, and Pittsburgh. In the 1950s, the shipments were changed to taconite, a pelletized version of the best ores, created at the mines.

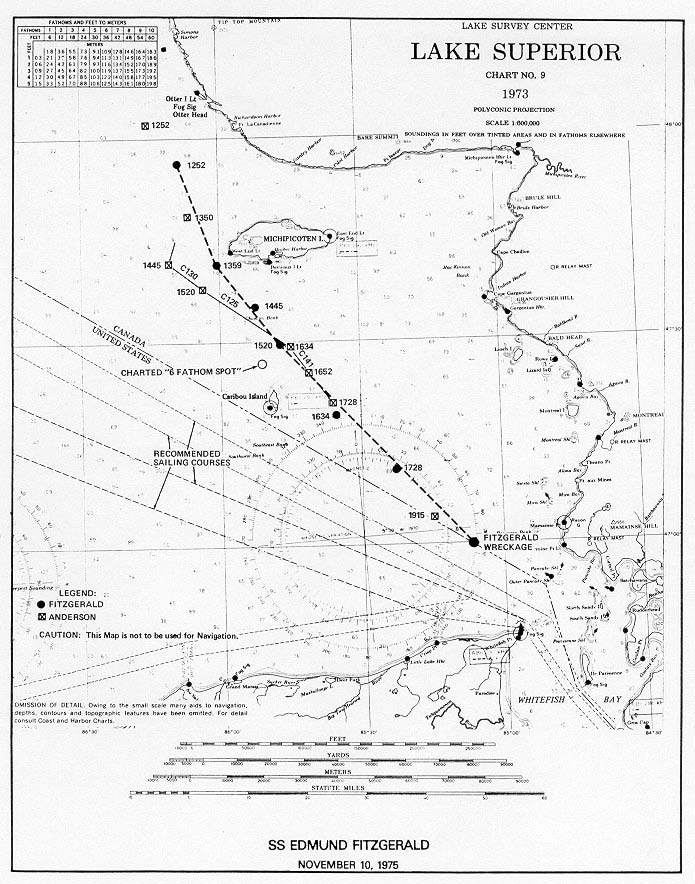

The probable respective routes of the Edmund Fitzgerald and the Arthur M. Anderson the fateful night of November 10, 1975

The SS Edmund Fitzgerald was launched in 1958 and was the largest ore transporter on the Great Lakes. Her length was seven hundred twenty-nine feet and seventy-five at the beam—more than two football fields long. For seventeen years the “Titanic of the Great Lakes” shipped out of Duluth, delivering taconite pellets to Detroit, Toledo and other ports. By ore freighter standards the “Mighty Fitz” was positively luxurious with deep pile carpeting, tile bathrooms, and leather swivel chairs in the guest lounge. The crew quarters were air-conditioned and fully stocked pantries for the two dining rooms. The pilothouse boasted state-of-the-art nautical equipment and an elegant map room.

The Northwest Mutual Company named the ship after its president and chairman of the board, a man whose grandfather and uncles had all been lake captains. The sideways launch of the new ship in 1958 created a wave so large it doused the 15,000 spectators! The Fitz quickly became the record-setting workhorse and flagship of the Columbia Transportation Fleet. She became a favorite of boat watchers, and the captain piped music day and night over the ship’s intercom system. Ore-carrying ships were built to last fifty years, but the Edmund Fitzgerald met an ill-wind of providence on that Sunday in 1975, after leaving with a load of taconite from her Superior, Wisconsin port, bound for Tug Island near Detroit.

Captain Ernest Michael McSorley (1912-1975)

The Arthur M. Anderson unloading at Huron, Ohio, November 29, 2008

Captain Earnest M. McSorley decided to follow the regular route despite the weather report of a possible storm, a normal forecast for that time of year. The Fitz was joined by the Arthur M. Anderson out of Two Harbors, Minnesota bound for Gary, Indiana. At 7:00 p.m., the National Weather Service issued a gale warning for the whole of Lake Superior. Both ships altered course seeking shelter along the Ontario shore, where they encountered a winter storm at 1:00 a.m. By 2:00 the Anderson registered winds of 50 knots (about 58 miles per hour). Within forty-five minutes snow obscured visibility and the Anderson lost sight of the Fitz. Captain McSorley radioed the Anderson that his ship was taking on water and a few minutes later reported they had lost their radar and were slowing down to rely on the smaller ship for guidance. McSorley hailed any ships in the area for information about a nearby lighthouse and reported that the Fitzgerald was listing badly and the seas were “over the deck” in the “worst seas I’ve ever been in.” The Arthur M. Anderson recorded waves twenty-five feet high and sustained winds at fifty knots and gusts up to eighty-six knots. At 7:10 Captain McSorley radioed that they were “holding their own,” but was never heard from again. There are many theories regarding the breakup and sinking of the ship, too many to summarize in this brief article.

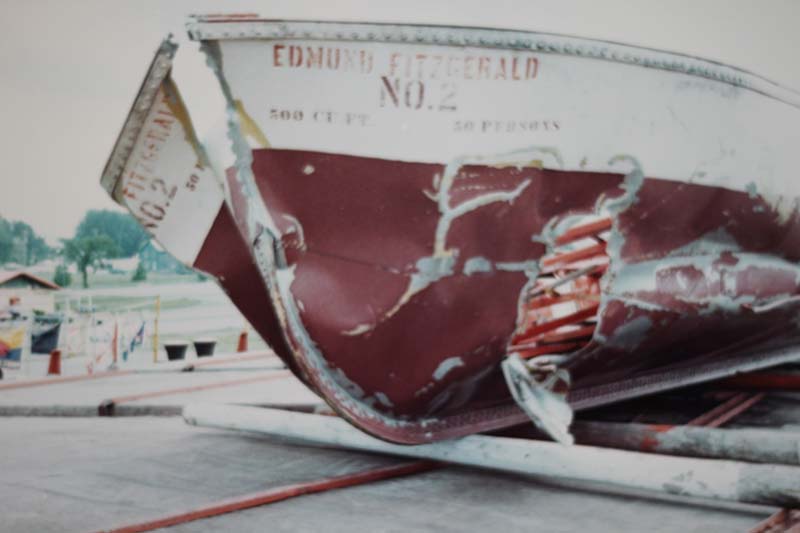

Lifeboat No. 2, recovered after the wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald

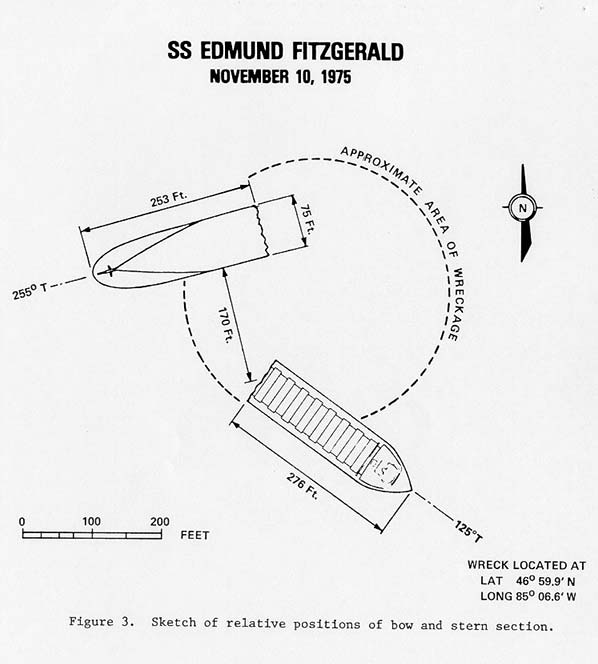

A three-day search off Whitefish Point turned up a few lifeboats and wreckage, but no survivors or the ship. A Navy Lockheed P-3 Orion flying over the region with special radar found the Edmund Fitzgerald in two pieces, fifteen miles west of Deadman’s Cove in 530 feet of Canadian waters on November 14. A number of dives have been held on the wreck, and the ship’s bell has been recovered. The remains of one seaman with a life vest was recovered. An historical marker has been erected at Whitefish Point, Michigan and a replica of the bell etched with the twenty-nine crewmen’s names is on display at the Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum in Chippewah County, Michigan. Canadian singer Gordon Lightfoot composed and sang “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald” in 1976. It became one of the most famous ballads in American history.

A sketch of the wreck as it was found

Canadian musician Gordon Lightfoot, who commemorated the loss with his famous ballad, “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald” in 1976

Keep your eyes open for a new and exciting Landmark Events tour (late August or September of 2023) as we visit the numerous historical sites of the Duluth, Minnesota area, including the William A. Irvin, a floating iron ore ship museum that plied the Lakes for 40 years.

Annual lighting of the Split Rock Lighthouse to commemorate the loss of the Edmund Fitzgerald

Image Credits: 1 Great Lakes (Wikipedia.org) 2 SS Edmund Fitzgerald (Wikipedia.org) 3 Route map (Wikipedia.org) 4 Captain McSorley (Wikipedia.org) 5 SS Arthur M. Anderson (Wikipedia.org) 6 Lifeboat (Wikipedia.org) 7 Wreck map (Wikipedia.org) 8 Gordon Lightfoot (Wikipedia.org) 9 Split Rock Lighthouse (Wikipedia.org)