“They that go down to the sea in ships, that do business in great waters; these see the works of the Lord, and his wonders in the deep. For he commandeth, and raiseth the stormy wind, which lifteth up the waves thereof. They mount up to the heaven, they go down again to the depths: their soul is melted because of trouble.” —Psalm 107:23-26

The Sinking of the RMS Titanic, April 15, 1912

![]() he story is a familiar one to Americans. The mighty White Star Line of the United Kingdom built the fastest passenger ship afloat — RMS Titanic. On her maiden voyage from Southampton to New York, it struck an iceberg in the middle of the night due to several factors. It quickly took on water and in less than two and a half hours, it sank into the North Atlantic, killing more than fifteen hundred passengers. The sinking shocked the world, and the interest it generated has not abated. The wreck was located in 1985, 12,500 feet below the ocean surface, suddenly regenerating world-wide interest in the event. Perhaps no such tragedy in history has been more minutely analyzed by professional and amateur historians.

he story is a familiar one to Americans. The mighty White Star Line of the United Kingdom built the fastest passenger ship afloat — RMS Titanic. On her maiden voyage from Southampton to New York, it struck an iceberg in the middle of the night due to several factors. It quickly took on water and in less than two and a half hours, it sank into the North Atlantic, killing more than fifteen hundred passengers. The sinking shocked the world, and the interest it generated has not abated. The wreck was located in 1985, 12,500 feet below the ocean surface, suddenly regenerating world-wide interest in the event. Perhaps no such tragedy in history has been more minutely analyzed by professional and amateur historians.

The RMS Titanic struck an iceberg at 11:40pm on April 14, 1912 and sank a few hours later in the early morning hours of April 15. It now lies on the floor of the North Atlantic, some 12,500 feet below the ocean’s surface.

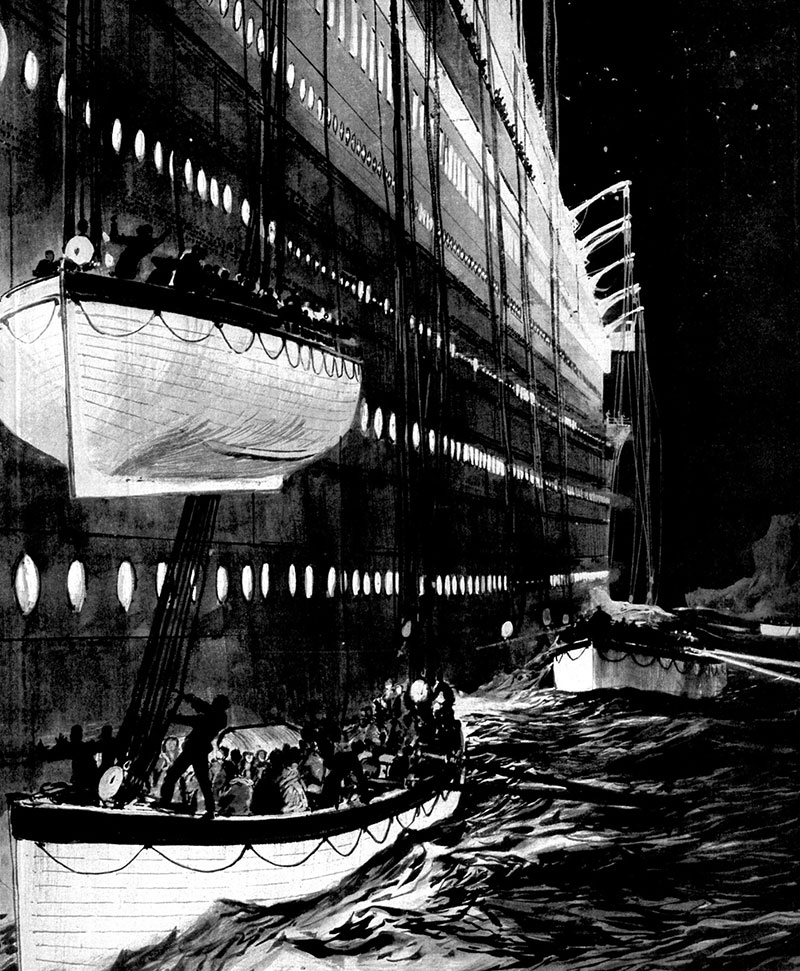

A number of factors have given the Titanic story a poignancy that captures the imagination, and the controversies have kept the story alive. The vessel carried only enough lifeboats to save 1,178 people, about half of the total aboard. As it happened, less than 800 made it safely away, with some boats less than half-full. The more than 700 third-class passengers were ensconced far below the lifeboat decks and did not have maximum access to escape to them. Although the crew followed the “women and children first” protocol, some men snuck aboard the lifeboats to insure their own safety.

“Leaving the Sinking Liner”, a depiction by artist Charles Dixon of Titanic survivors being lowered in the lifeboats into the water

Survivors aboard Titanic’s Collapsible Boat D approach RMS Carpathia at 7:15am, April 15, their vessel partly filled with ice-cold seawater

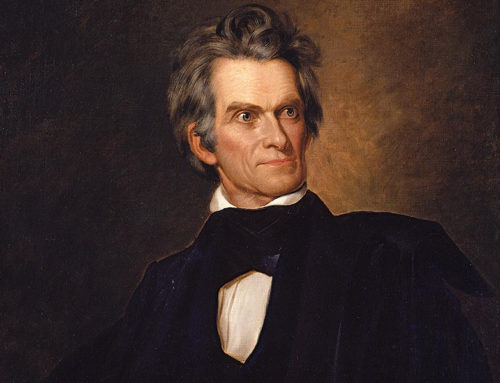

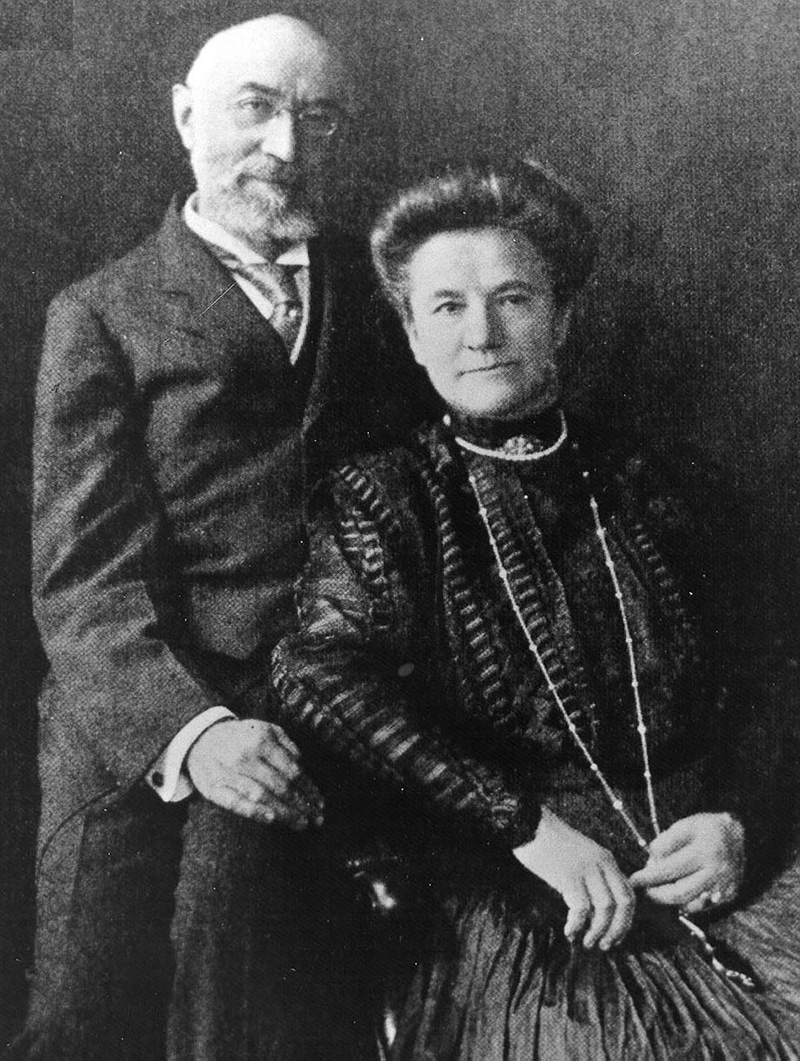

The stories of heroism and sacrifice are the ones that ought to grip us the most. And there is no shortage of those. Some of the richest men in the world were aboard the Titanic and they did not try to buy their way to safety, but awaited the loading of women and children, then went down with the ship. John Jacob Astor, worth well over two billion dollars (in today’s currency) helped his pregnant wife into a lifeboat then stood back. He was last seen alive leisurely smoking with famous detective fiction writer Jacques Futrelle as the ship went under. Isidor Strauss, the owner of Macy’s Department Store, Confederate veteran, and legendary philanthropist, sat on the deckchairs holding hands with his wife Ida, who refused to leave him though it meant her death.

Isidor Strauss (1845-1912) and his wife Ida (1849-1912)

John Jacob Astor (1864-1912) and his wife, Madeleine (1893-1940)

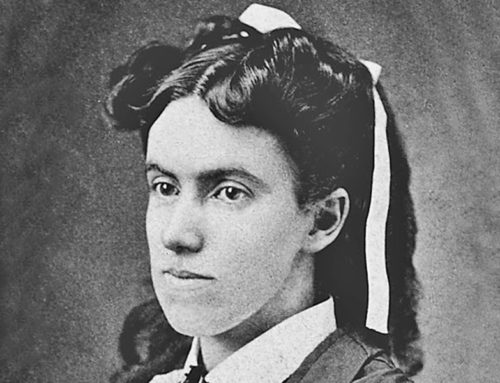

Jacques Futrelle (1875-1912)

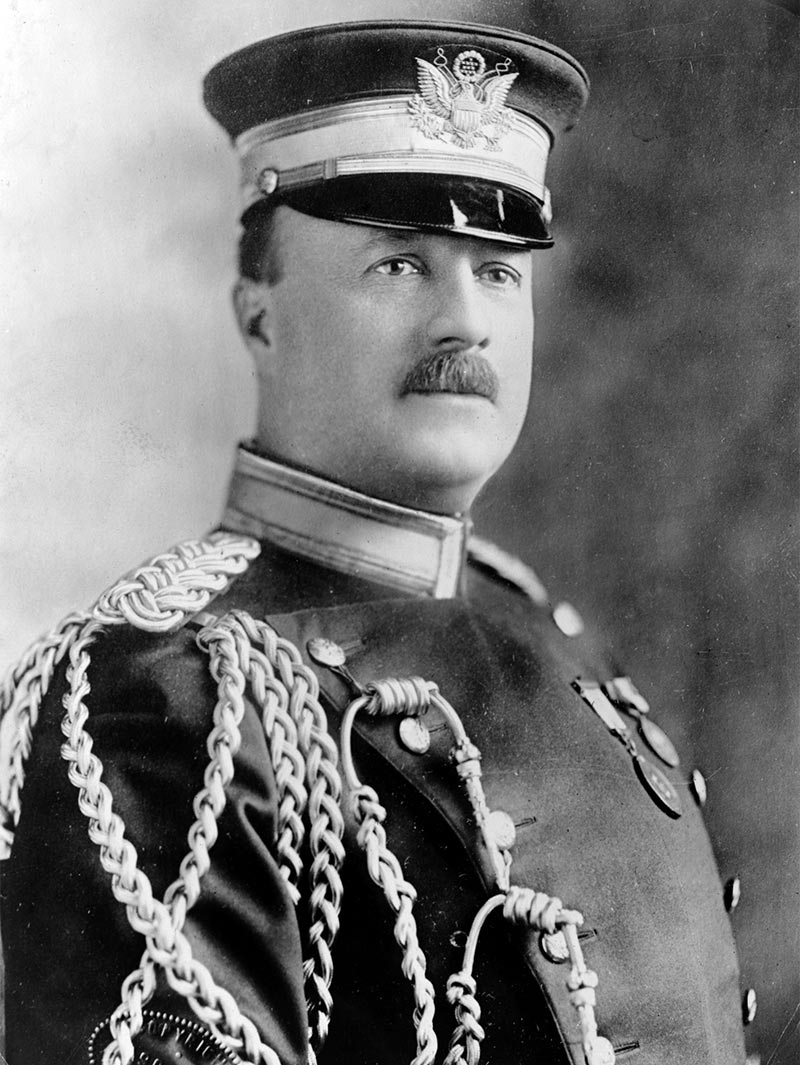

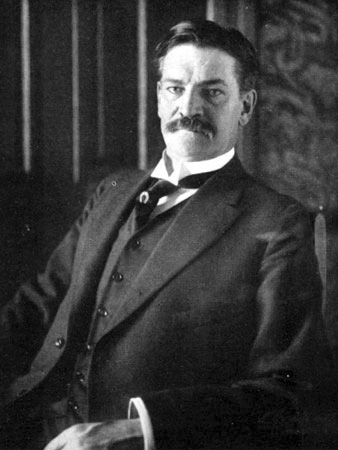

Two men with the eponymous name of Archibald (from the old German: Arche-Genuine, Bald-bold), saved countless women and children, loading them into lifeboats and keeping back men who would usurp their places. Archibald Butt was the chief of protocol in the Roosevelt and Taft White Houses, a Southern gentleman of the deepest courage and sacrifice and Archibald Gracie, son of the Confederate General of the same name, and a man who stepped up when his crowed hour for heroism arrived. Both went down with the ship, though Gracie survived the sinking, standing on an upside-down collapsible raft all night till rescued.

Archibald Butt (1865-1912)

Archibald Gracie IV (1858-1912)

Crew members did their duty and paid with their lives. Telegraphers Phillips and Bride stayed in their cabin sending wireless SOS messages till the water was sloshing into the room. Phillips did not survive. 1st Officer William McMaster Murdoch took charge of the lifeboat loading for the starboard evacuation, which saved 75% of the passengers who survived. He did not. Second Officer Charles Lightoller loaded passengers on the port side, strictly enforcing women and children first. He stayed till the ship went down and he was sucked against a grate, then blown away from the ship when a boiler exploded. He helped keep thirty men alive, standing all night on the overturned collapsible boat hull. He survived and, by the Providence of God, was twice decorated for bravery in WWI, just three years later, and saved 127 British soldiers at Dunkirk by sailing a private yacht back and forth in the beginning of WWII.

Charles Lightoller (1874-1952) second officer of the RMS Titanic, and the most senior crew member to survive

In this colorized photograph, Ned Parfett, best known as the “Titanic paperboy”, stands outside the White Star Line offices in London holding a newspaper banner advertisement about the disaster, April 16, 1912

These are just a few of the many individual stories of the Titanic, attesting to both heroism and cowardice, but especially the Christian “law of the sea,” that women and children were to receive precedence in rescue, even to the sacrificial death of the men who either helped or stood back to await their own end.

Image Credits: 1 Titanic sinking (Wikipedia.org) 2 Lowering the lifeboats (Wikipedia.org) 3 Collapsible D (Wikipedia.org) 4 John Jacob and Madeleine Astor (Wikipedia.org) 5 Jacques Futrelle (Wikipedia.org) 6 Isidor and Ida Strauss (Wikipedia.org) 7 Archibald Butt (Wikipedia.org) 8 Archibald Gracie (Wikipedia.org) 9 Charles Lightoller (Wikipedia.org) 10 Paperboy (Wikipedia.org)