“If the Son therefore shall make you free, ye shall be free indeed.” —John 8:36

William Tell and Swiss Independence, November 18, 1307

e all recognize the finale of Gioachino Rossini’s William Tell Overture, but how many know what the Swiss patriot actually accomplished, or if he existed at all? When I was a youngster, William Tell was a hero to me, with a crossbow over his shoulder and evil soldiers at his heels. Tell was a local farmer and famous hunter, who was accosted in town one day in the Canton of Uri in Switzerland, by bailiff Gessler, an agent of the duke of Austria. Refusing to uncover his head when passing by a pole with a Habsburg hat on it, Tell was seized for disrespecting the monarch. An apple was placed on Tell’s son’s head, and, because he was a renowned marksman, the peasant was ordered to shoot it off with one shot of his crossbow at 120 paces. Tell drew two quarrels from his sheath. He fired once and split the apple in two without injuring his son. The bailiff asked why he drew two bolts and Tell replied, “if I had harmed my son, the second one was for you, and I would not have missed.”

e all recognize the finale of Gioachino Rossini’s William Tell Overture, but how many know what the Swiss patriot actually accomplished, or if he existed at all? When I was a youngster, William Tell was a hero to me, with a crossbow over his shoulder and evil soldiers at his heels. Tell was a local farmer and famous hunter, who was accosted in town one day in the Canton of Uri in Switzerland, by bailiff Gessler, an agent of the duke of Austria. Refusing to uncover his head when passing by a pole with a Habsburg hat on it, Tell was seized for disrespecting the monarch. An apple was placed on Tell’s son’s head, and, because he was a renowned marksman, the peasant was ordered to shoot it off with one shot of his crossbow at 120 paces. Tell drew two quarrels from his sheath. He fired once and split the apple in two without injuring his son. The bailiff asked why he drew two bolts and Tell replied, “if I had harmed my son, the second one was for you, and I would not have missed.”

Detail of memorial statue of William Tell and his son in Altdorf, Switzerland

William Tell takes aim at the apple placed atop his son’s head

The infuriated Gessler arrested Tell and set off across the treacherous Lake Lucerne to incarcerate him in a dungeon “where he never again would see the light of day or the moon and stars at night.” Just before reaching shore, in a storm, Tell leaped ashore, kicking the boat back into the waves, and made his way twenty miles through a narrow pass in the Alps, where he lay in wait for his pursuers. Right on cue, they arrived only to be felled by his crossbow shots. He was shortly joined by three other men from other cantons, and they swore an oath still memorized by Swiss lads to this day:

Uri arm of Lake Lucerne near Morschach, Switzerland

“To assist each other with aid and every counsel and every favor, with persons and goods, with might and main, against one and all, who may inflict on them any violence, molestation or injury, or may plot any evil against their persons or goods.”

William Tell leaps ashore and kicks the boat back into the waves

From that humble beginning in 1307, a successful national war of liberation was fought against the Austrian Habsburg dynasty throughout the cantons of Switzerland. The story is cherished by the Swiss and a crossbow adorns a stamp on every export that crosses Swiss borders.

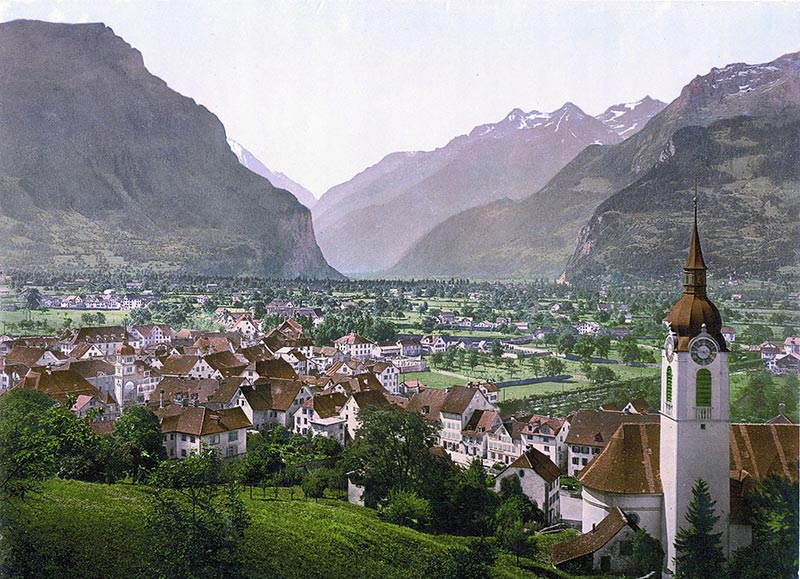

Altdorf, Canton of Uri, Switzerland (circa 1890-1905)

Many historians today challenge the story and claim it pure myth, the main lineaments of it borrowed from an old Norse tale. The first written account of the William Tell story was printed two hundred fifty years after the event by a historian named Aegidius Tschudi. Prior to about 1570, the tale was derived from oral tradition, which of course, by itself, does not make it untrue. The dates for the story of William Tell do not match the historical context for 1307, but dating precision is often a problem for historians, especially when hundreds or thousands of years are involved. In the mid-eighteenth century, a scholar from Bern—Gottlieb de Haller—read old Viking stories from Denmark, one of which recounted the exact story of William Tell, except the tale involved King Harald Bluetooth and a chieftain named Toko.

The story revolves around a drunken feast in which Toko boasted of his prowess with a bow and arrow, a typical Viking thing to do. The King challenged Toko and ordered him to shoot an apple off his son’s head, also a very Viking-like action at a drunken party. And the story plays out in similar fashion. Why can’t an identical story be true in two different places in history, and might the Swiss official have heard the story from a Danish source himself, and thought the contest worthy of a trial? Once the Swiss story was challenged, many other “historians” have gotten in on the revision over the centuries, including very recent histories of Switzerland.

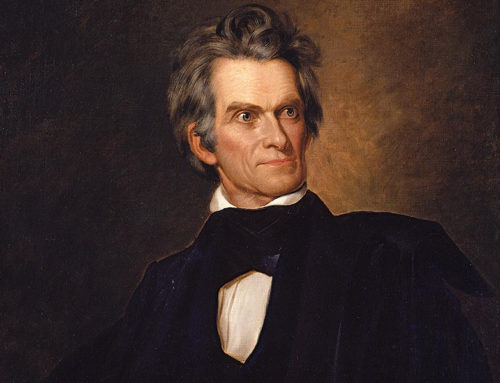

Harald Bluetooth (c. 910 – c. 986/87) King of Denmark and Norway

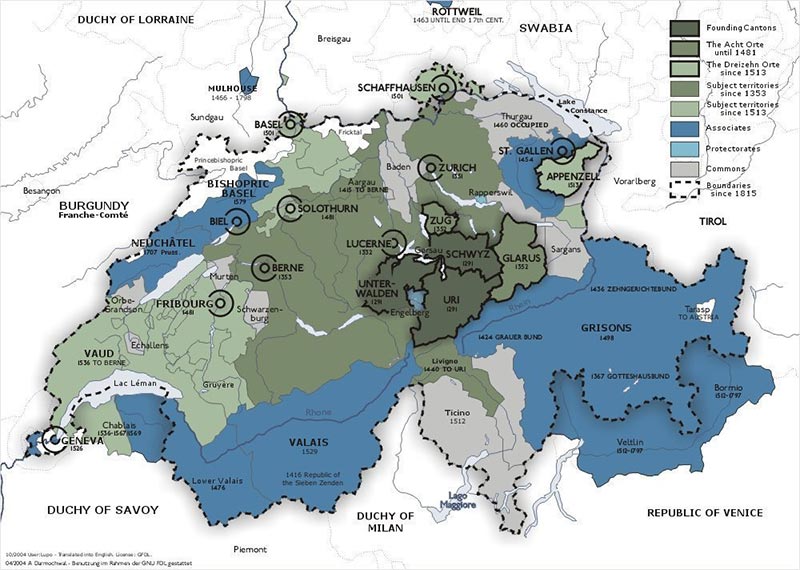

Map showing the Old Swiss Confederacy from 1291 to the sixteenth century

The sturdy and highly armed peasants of the Swiss mountains and valleys did rise up against the Austrian Empire and did defeat the gaudy knights sent against them from time to time. A confederation was established, joined by other cantons. William Tell’s existence and story can neither be proven nor disproven by historians. His story has also inspired people of other countries in every century. Rossini’s William Tell Overture had to be changed to be about Scotland when it debuted in Milan, since that city was part of the Habsburg Empire at the time. But we know the real story. Listen to the finale and try to believe that the tale is not exactly as the Swiss have heard it for 700 years! I like the Tokyo Symphony’s rendition the best: