“But they deceived Him with their mouth and lied to Him with their tongue.” —Psalm 78:36

Chief Joseph Surrenders, October 5, 1877

![]() ollowing the American War Between the States, the United States government reorganized the army after demobilizing a million men. In 1866 due to demands for bluecoats to occupy the conquered but discontented and sometimes rebellious South, and continued conflicts with natives in the West who still resisted the stealing of their lands by pioneers, miners, farmers, and the U.S. government, a little over 50,000 soldiers were kept in the army or recruited for post-war service. Cavalry regiments of twelve companies each, infantry regiments and artillery batteries, were sent to garrison the forts across the western territories and pacify the highly mobile tribes who defied resettlement on “reservations.” The generals who were sent westward to enforce President Ulysses S. Grant’s policies often already acquired savage reputations for suppressing civilian populations, as well as extensive combat experience—William T. Sherman, Phillip Sheridan, George Crook, and the flamboyant insubordinate bon vivant, George Armstrong Custer. The list also eventually included the one-armed Christian General Oliver Otis Howard, known for his humanitarian instincts.

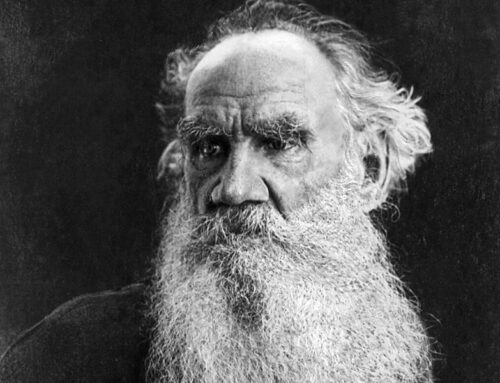

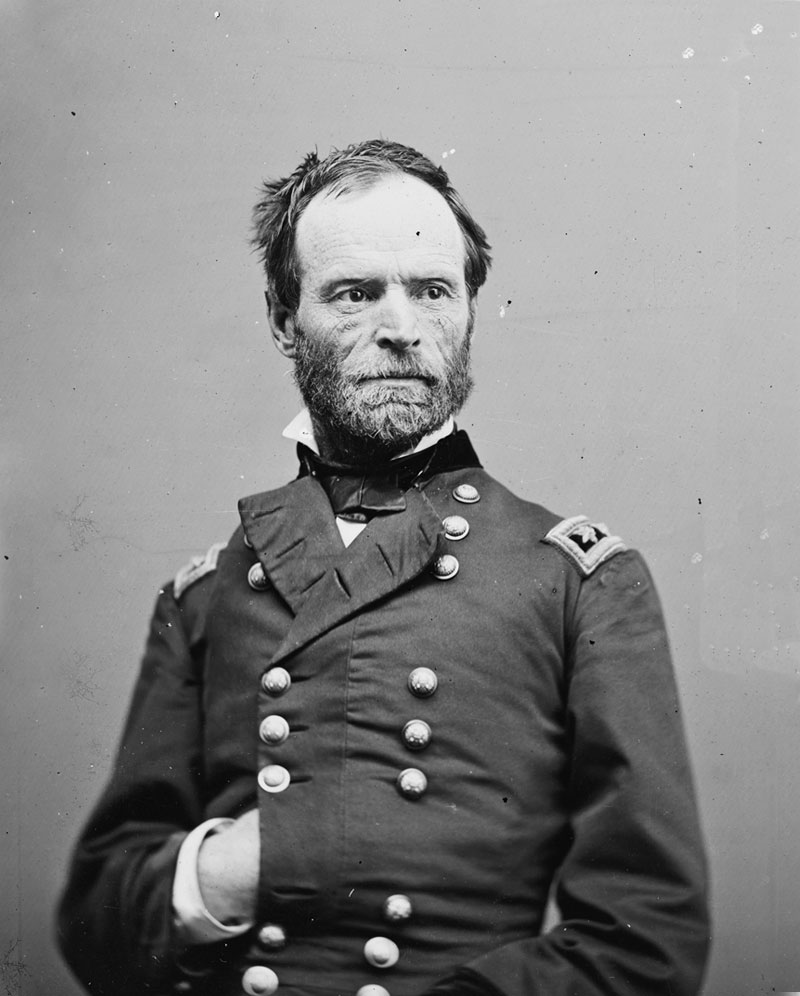

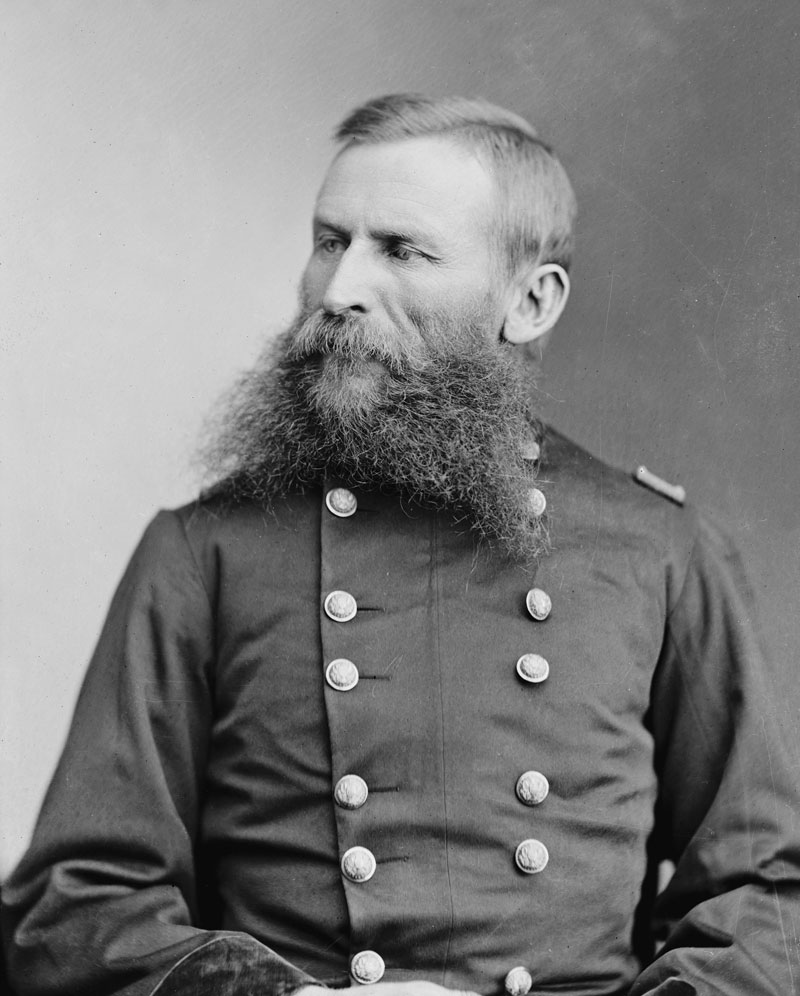

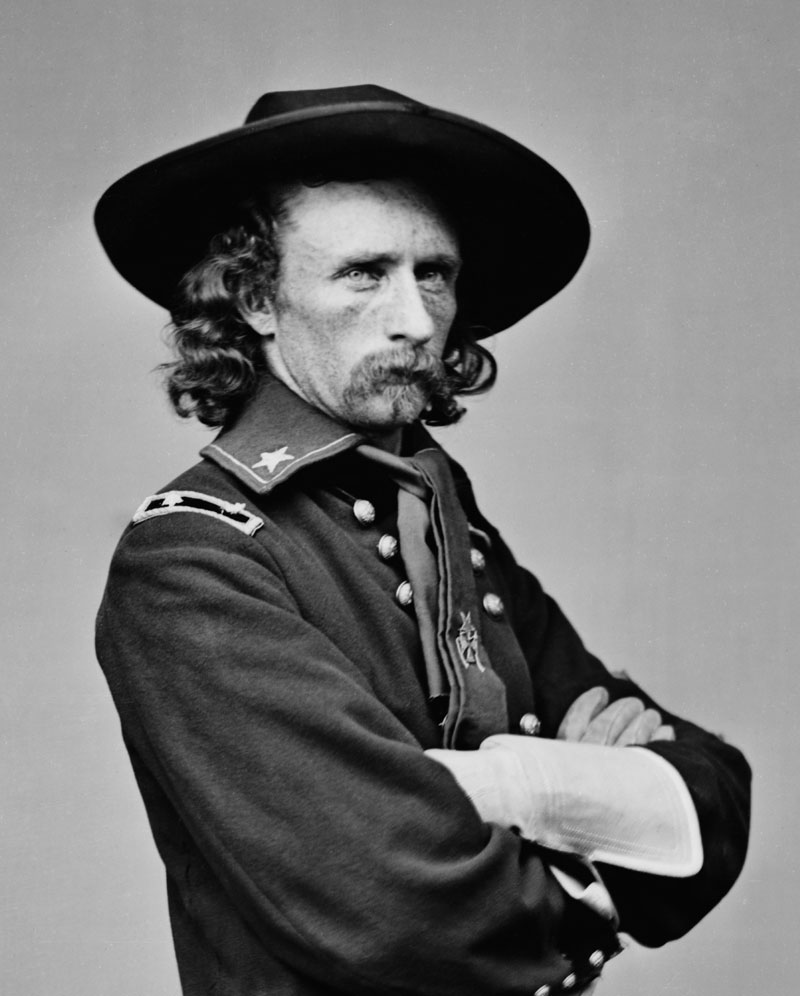

ollowing the American War Between the States, the United States government reorganized the army after demobilizing a million men. In 1866 due to demands for bluecoats to occupy the conquered but discontented and sometimes rebellious South, and continued conflicts with natives in the West who still resisted the stealing of their lands by pioneers, miners, farmers, and the U.S. government, a little over 50,000 soldiers were kept in the army or recruited for post-war service. Cavalry regiments of twelve companies each, infantry regiments and artillery batteries, were sent to garrison the forts across the western territories and pacify the highly mobile tribes who defied resettlement on “reservations.” The generals who were sent westward to enforce President Ulysses S. Grant’s policies often already acquired savage reputations for suppressing civilian populations, as well as extensive combat experience—William T. Sherman, Phillip Sheridan, George Crook, and the flamboyant insubordinate bon vivant, George Armstrong Custer. The list also eventually included the one-armed Christian General Oliver Otis Howard, known for his humanitarian instincts.

William Tecumseh Sherman (1820-189

Philip Henry Sheridan (1831-1888)

George R. Crook (1828-18

George R. Crook (1828-18

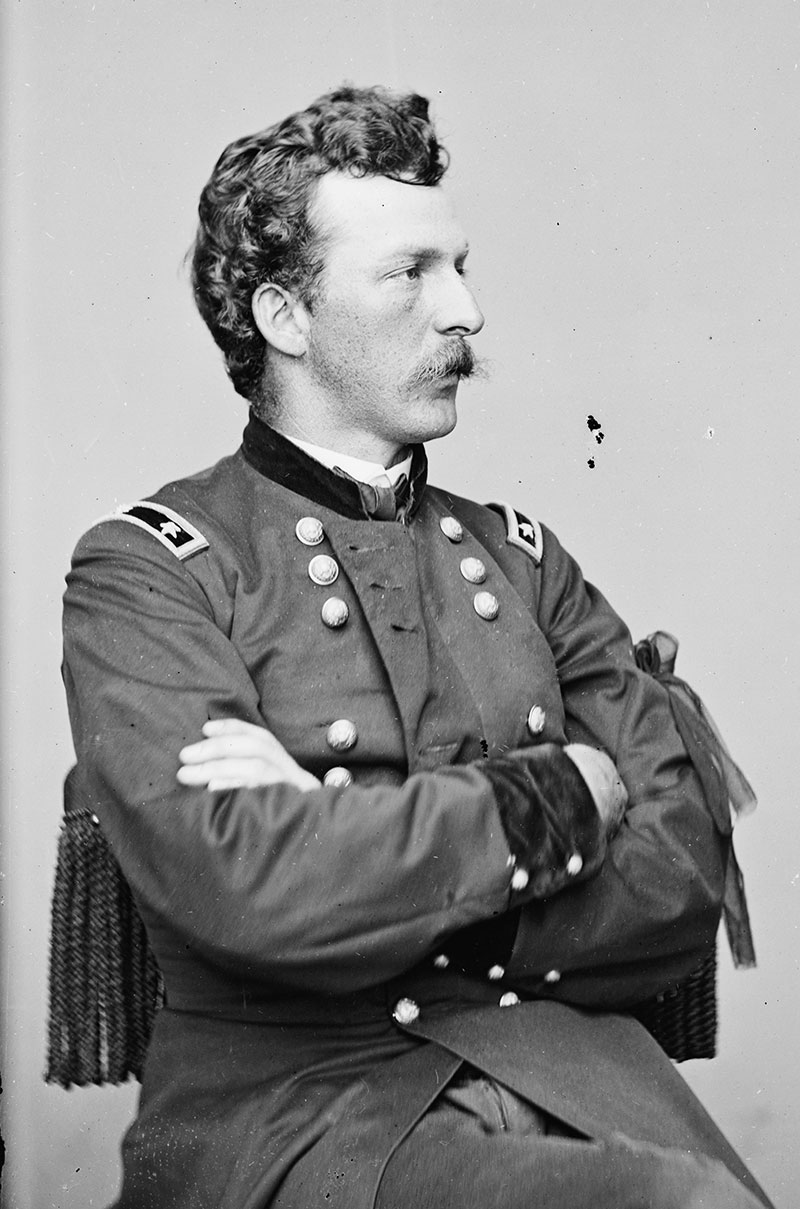

George Armstrong Custer (1839-18

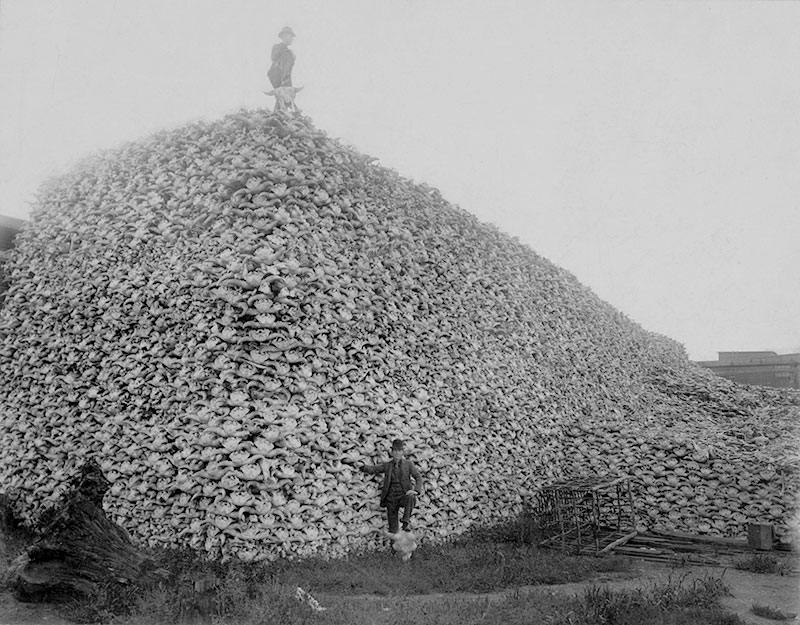

Stories of war with the Sioux, Cheyenne, Modocs, and others filled the Eastern newspapers, and voters pressed for final resolution of the “Indian problem.” Treaties were struck and just as quickly broken by one side or the other. Pioneers murdered natives and vice versa in a seeming never-ending cycle of misunderstanding, revenge and retribution. The wild animals of the prairies, such as the buffalo, were slaughtered with reckless abandon by white hunters, forcing the tribes to remain on the move or submit to being herded themselves onto barren reservations. Given the disparities in numbers and firepower, the defeat of the natives was a forgone conclusion. Nonetheless, some of the independence-minded chiefs and their families did not go quietly. One of the most discomfiting and successful of the group was Chief Joseph and his Nez Perce band.

Two men stand with a mountain of Bison skulls to be processed and used for glue, fertilizer, dye/tint/ink and other industrial products

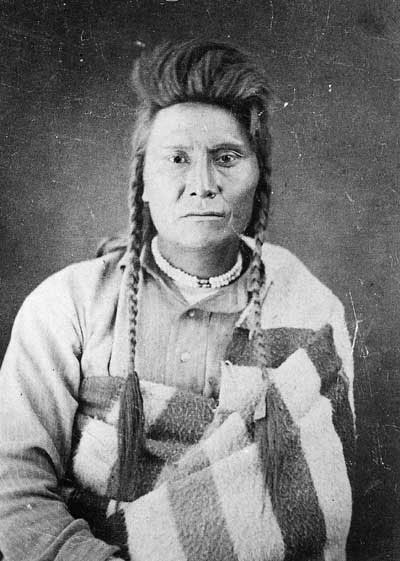

Chief Joseph (1840-1904)

Chief Joseph was a leader of the Wallowa band in Oregon territory. He was the son of Chief Joseph and popularly known as “Young Joseph” apart from his given name of In-Mut-Too-Yah-Lat-Kekht (literally Thunder Rolling in the Mountains). The Rev. Henry H. Spalding, a Presbyterian missionary who came west with the Whitman missionaries, settled among the Nez Perce. In 1836, four years before the birth of Young Joseph, Old Joseph made a profession of faith and was baptized, but later had a falling out with Spalding and renounced his faith. In 1855 the Nez Perce chief and his son attended a treaty council together at Walla Walla where several of the chiefs agreed to the reservation because it included the Wallowa homeland and most of the other Nez Perce lands in Oregon, Washington and Idaho where the band roamed. Settlers and miners poured into the new Treaty lands, compelling the United States government to call for another treaty in 1863 in which the tribes were confined to a small area on the fringes of their former lands. The treaty was signed by only one chief, named Lawyer!

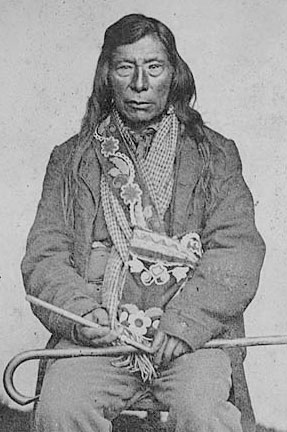

Hallalhotsoot or “Lawyer” (c. 1797

Chiefs Joseph, Looking Glass, and White Bird with a band of warriors in the spring of 1877

Chief Joseph led the “non-treaty” Nez Perce and returned to Wallowa country where he died and Young Joseph became chief in 1871. Young Joseph was described as a tall handsome man, powerfully built and with a serious look. General Howard met with Joseph and the other chiefs and told them they had to move to the reservation within thirty days or the army would “move them by force.” Joseph took his tribe to Camas Prairie in Idaho to meet one last time with his fellow chiefs. While there, some young Nez Perce warriors rode off to avenge another murder by the miners. Joseph and three other chiefs decided to take their Nez Perce bands and move to Montana where the buffalo still roamed.

The Battle of the Big Hole was fought in Montana Territory, August 9–10, 1877, between the United States Army and the Nez Perce tribe

The Battle of the Big Hole was fought in Montana Territory, August 9–10, 1877, between the United States Army and the Nez Perce tribe

Joseph became the camp chief in charge of about 800 women and children as they braved the cliffs, mud and rugged Bitterroot Mountains. They agreed not to molest any whites, even stopping for several days at Stevensville to trade and rest. Soldiers under command of Colonel John Gibbon caught up to the fleeing natives where the peace was shattered at the Battle of Big Hole. In the surprise attack the soldiers fired into the tepees killing eighty Nez Perce, including fifty women and children. Chief Joseph said after the wars that the Nez Perce never killed women and children, for “they would be ashamed to do so.” Gibbon lost thirty-four men. The chase resumed, and Joseph led them on a trail that lasted a thousand miles.

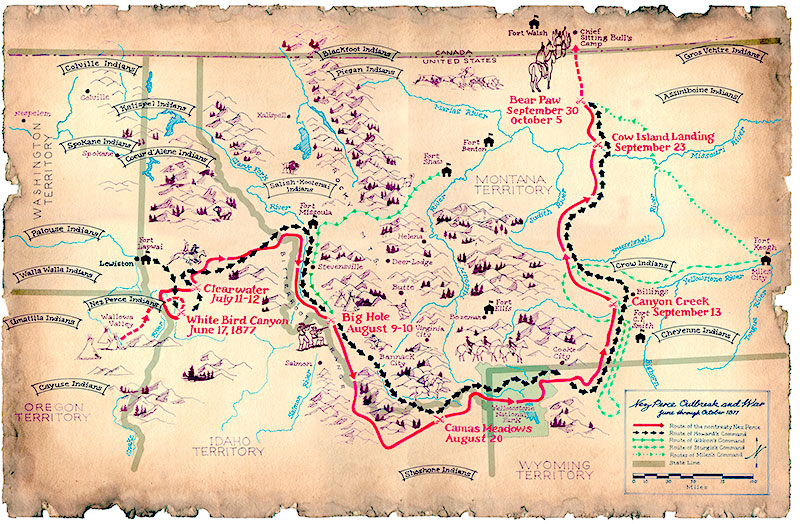

Map of the 1877 flight of the Nez Perce under Chief Joseph

Map of the 1877 flight of the Nez Perce under Chief Joseph

The Indians entered the Yellowstone National Park where they ran into several parties of tourists, and two of them were killed by angry young warriors. Joseph eluded his captors by crossing the Absaroka Range in places deemed impassable by their pursuers. It was now September of 1877 and the Nez Perce had gotten within a few miles of the Canadian border, when General Miles caught up to them. Two hundred made it into Canada, the rest, exhausted and starving and dragging their wounded on travois, stopped, and Joseph met Miles and Howard on October 5. He handed over his rifle. His words to the generals were written down by a translator, now considered one of the great speeches of American history:

An emaciated and grieving Chief Joseph, three weeks after the surrender

“It is cold, and we have no blankets; the little children are freezing to death. My people, some of them, have run away to the hills, and have no blankets, no food. No one knows where they are—perhaps freezing to death. I want to have time to look for my children, to see how many I can find. Maybe I shall find them among the dead. Hear me, my chiefs! I am tired; my heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands, I will fight no more forever.”

He surrendered his tribe after General Miles promised they would be returned to their reservation. The ailing and wounded band were then escorted to North Dakota, then to a camp in Kansas and finally, in 1878 to exile in Indian Territory in Oklahoma, far far from Oregon and Idaho. Joseph, the last of the Nez Perce chiefs, was lionized and admired across the United States, even meeting President Rutherford B. Hayes and members of Congress. In 1885 Joseph and 118 other exiles were packed in a train and shipped to the Colville Reservation in central Washington, where he died, in his tepee, in 1904.

Nelson Appleton Miles (1839-1925)

Image Credits: 1 Gen. Sherman (Wikipedia.org) 2 Gen. Sheridan (Wikipedia.org) 3 Gen. Crook (Wikipedia.org) 4 Gen. Custer (Wikipedia.org) 5 Bison Skulls (Wikipedia.org) 6 Chief Joseph (Wikipedia.org) 7 Chief Lawyer (Wikipedia.org) 8 Chiefs and Warriors (Wikipedia.org) 9 Big Hole Battlefield (Wikipedia.org) 10 Map: 1877 Flight of the Nez Perce (Wikipedia.org) 11 Chief Joseph Surrendered (Wikipedia.org) 12 Gen. Miles (Wikipedia.org)