“But I say to you, love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you.” —Matthew 5:44

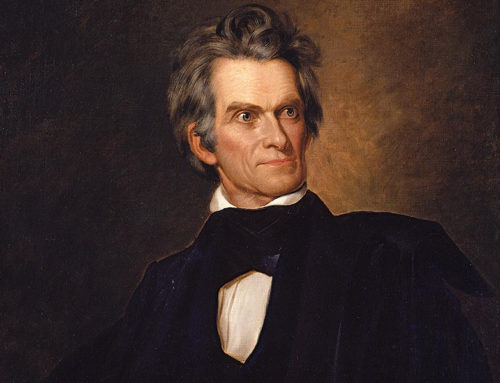

John Adams Inaugurated, March 4, 1797

A New Jersey delegate to the Second Continental Congress said it best:

“The man to whom the country is most indebted for the great measure of independence is Mr. John Adams . . . I call him the Atlas of American independence. He it was who sustained the debate, and by force of his reasoning demonstrated not only the justice, but the expediency of the measure.”

Adams, the man who hung his father’s hat, which he inherited, on the same peg in church, would leave a legacy to succeeding generations which lives on today as the United States of America. From assisting James Otis with his opposition to the Writs of Assistance, to helping negotiate the peace treaty with England in 1783, Adams represented the “mind” of the Revolution. That alone would make him one of the greatest men of our history. He also served as Vice President under George Washington. On March 4, 1797 John Adams was inaugurated as President of the United States.

John Adams (1735-1826), was an attorney, diplomat, and Founding Father of the United States, who served as the first Vice President (1789-1797) and as the second President (1797-1801)

After graduation from Harvard, Adams taught school, read law, and married Abigail Smith, a loving bond which lasted fifty-four years and produced five children. Adams never flinched from controversy, especially when principle was involved. He defended the British soldiers after the “Boston Massacre” and won his case in a hostile environment. Eschewing the promotion and privileges offered him by the Royal authorities, the Boston lawyer published essays against the stamp tax levied by Parliament, thus identifying himself with the burgeoning resistance to Imperial tyranny. No one knew more about constitutional law than Adams and he deployed his arguments on behalf of Massachusetts. He was elected to both the First and Second Continental Congresses meeting in Philadelphia, where he served on thirty different committees. Although he was “a man built for friendships,” his unvarnished opinions clashed with his more conservative brethren. Behind the scenes, he wrote his wife about the various members of the Congress, a delightful and honest evaluation that entertains and informs scholars today.

Depiction of the Boston Massacre engraved by Paul Revere (1735-1818)

His closest friend in the Congress, Thomas Jefferson, wrote that Adams’s speech for independence, countering John Dickinson’s appeal for caution and time, was so powerful “it moved us from our seats . . . he was a Colossus on the floor.” He drafted the Massachusetts Constitution in 1779 and was sent by Congress to Europe on a diplomatic mission to appeal to the French and Dutch for financial aid and recognition of the new United States. He played a key role in the negotiation of the Treaty ending the War for Independence.

Adams lived a life of moderation, frugality, fortitude and industry — character traits that derived from the Puritan New England family culture bequeathed by his ancestors. Dissimulation had no place in his world — as one historian aptly put it, “unable to meet falsehoods halfway and unwilling to stop short of the truth, Adams was in constant battle with the accepted, the conventional, the fashionable, and the popular.” Personal integrity and seeking justice went hand in hand.

Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826), diplomat, architect, and Founding Father of the United States, who served as the second Vice President (1797-1801) and as the third President (1801-1809)

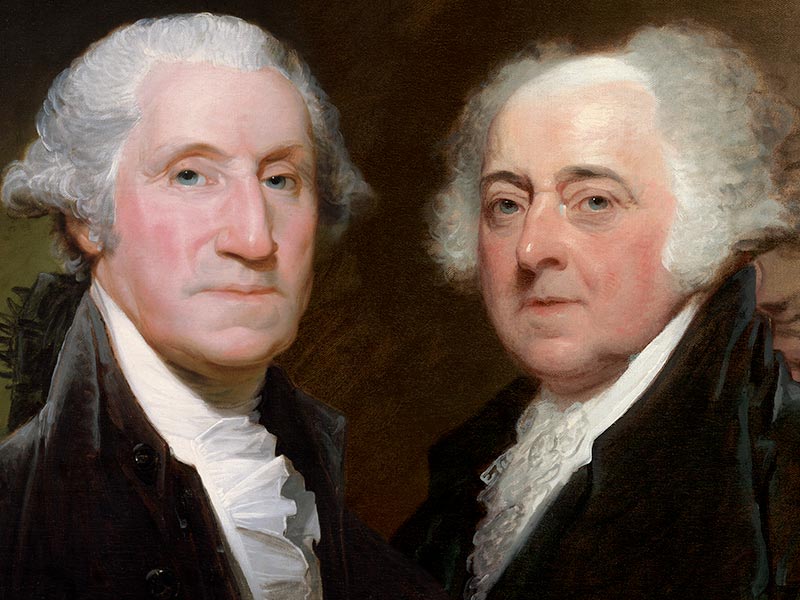

George Washington (1732-1799) and John Adams (1735-1826)

Twice elected Vice-President, he worked alongside George Washington, giving counsel and support. His admiration for Great Britain, disdain of the French Revolution, and attraction to a strong executive under the Constitution brought him into conflict with his friend Jefferson, a relationship that broke after the latter’s election to the Presidency in 1800. As President, Adams avoided all alliances with Europe save commercial relations. He met with strong opposition when he supported the Alien and Sedition Acts of Congress; unsurprisingly, his presidency proved combative and controversial.

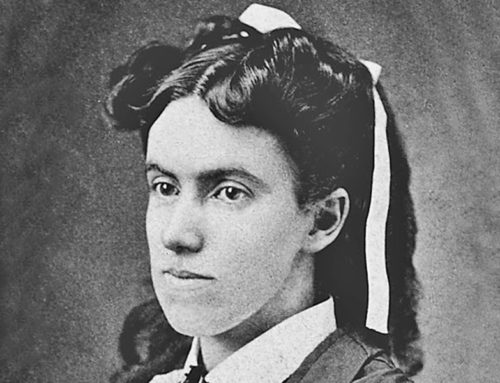

We know more about Adams’s family life than that of most Presidents. His correspondence with his wife and the success of his descendants in literary and public life provide insights absent in most men of his stature. One of his sons died in grievous alcoholism, estranged from his father. His son John Quincy became President in his own right and is renowned today for his enormous intellect (and library), experience in government which began with his father in his young teen years, and opposition to slavery, in concert with his father’s beliefs. While Adams knew and admired the Bible, and compelled his children to memorize it as much as possible he, nonetheless, denied the Trinity and ridiculed those who did believe.

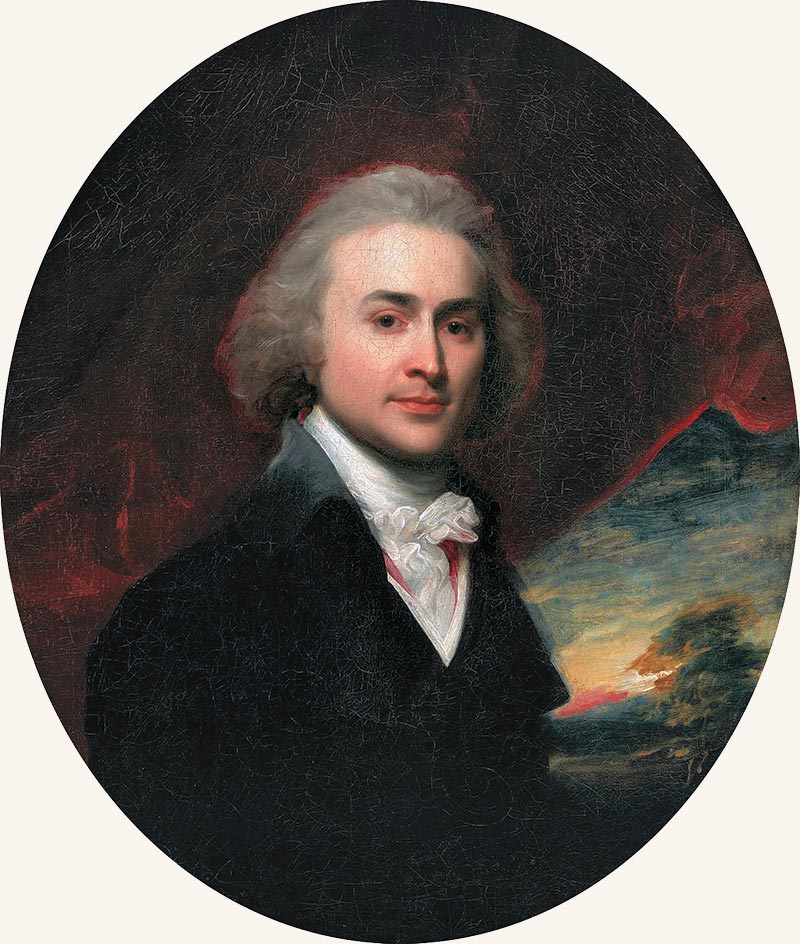

John Quincy Adams (1767-1848), second oldest of John and Abigail Adams’s six children, and sixth President of the United States (1825-1829)

John Adams and Thomas Jefferson are among those depicted at the signing of the Declaration of Independence, August 2, 1776

After their presidencies, Adams and Jefferson resumed their relationship with regular correspondence, available for reading today as an enlightening and enjoyable look into the friendship that made the Republic. They both died on the Fourth of July, 1826 on the fiftieth anniversary of the Declaration of Independence — a fitting end that only Providence could have orchestrated.

The final portrait of John Adams, made at the request of his son John Quincy, in 1823 three years before his father’s death

Image Credits: 1 John Adams (Wikipedia.org) 2 Boston Massacre (Wikipedia.org) 3 Thomas Jefferson (Wikipedia.org) 4 George Washington with John Adams (Wikipedia.org) 5 John Adams with George Washington (Wikipedia.org) 6 John Quincy Adams (Wikipedia.org) 7 Signing of the Declaration (Wikipedia.org) 8 John Adams, 1823 (Wikipedia.org)