“My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness.” —2 Corinthians 12:9

The Pilgrims Meet Samoset, March 16, 1621

![]() he pleasantly named ship, the Mayflower, had been rocking at anchor in the harbor since November of 1620. The three-masted, three-decked, and well-armed merchant ship brought one hundred three passengers and its crew of about thirty to Provincetown harbor after a perilous two-month journey across the Atlantic. Fatal, contagious diseases carried off fifty-three of the passengers and about half the crew in the four months they had braved out the “New England” winter. Most of the dead had been buried in the frozen ground at night, since the new settlers knew almost nothing about the natives of the land and did not want them to know their sad attrition rate. The English Pilgrims set up a makeshift camp along the shore and on a hill above a valley cut by a brisk stream. They called their hopeful settlement Plymouth.

he pleasantly named ship, the Mayflower, had been rocking at anchor in the harbor since November of 1620. The three-masted, three-decked, and well-armed merchant ship brought one hundred three passengers and its crew of about thirty to Provincetown harbor after a perilous two-month journey across the Atlantic. Fatal, contagious diseases carried off fifty-three of the passengers and about half the crew in the four months they had braved out the “New England” winter. Most of the dead had been buried in the frozen ground at night, since the new settlers knew almost nothing about the natives of the land and did not want them to know their sad attrition rate. The English Pilgrims set up a makeshift camp along the shore and on a hill above a valley cut by a brisk stream. They called their hopeful settlement Plymouth.

Mayflower in Plymouth Harbor

The Englishmen gathered on February 17 to hold their first official meeting about defending themselves in case of attack. Short, red-headed Miles Standish had been appointed captain and immediately took up his musket when two natives were spotted on the other hill above the creek. They fled when he approached, though he could hear many others in the near distance. Previous accounts of European contacts with the native inhabitants of coastal North America, in some cases, had included kidnapping and killing.

A recreation of Plimoth Plantation

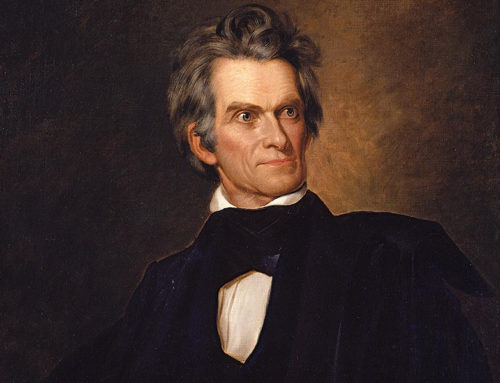

Captain Myles Standish (c. 1584-1656)

The master of the Mayflower ordered the iron cannons from the ship be mounted on the high hill from which the burgeoning colony would be constructed down to the harbor’s edge. On March 16 the men met again to discuss military matters when a stalwart native man emerged from the forest. He did not flee, but walked fearlessly toward the gathered colonists. He strode directly up Cole’s Hill toward the gathering and was stopped just short of the women and children. The colonists were likely fingering their muskets and swords, wondering what came next. The native raised his arm and said, “Welcome, Englishmen” to the utter astonishment of the Pilgrims.

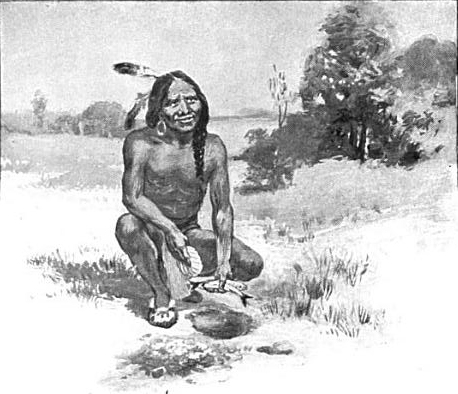

Samoset enters the village and exclaims in broken English, “Welcome, Englishmen!”

The black-haired native interlocutor towering over them was Samoset, a subordinate chief of the Abenaki tribe. He was apparently on a diplomatic mission to Chief Massasoit of the Wampanoags, who lived just south of Plymouth. Samoset had learned just enough English to converse, from English fishermen and sailors of trading vessels who developed commercial interests with his tribe. He informed the Englishmen, in his rudimentary English, that they were settling an area known as Patuxet and that their near tribal neighbors were the Wampanoag and Nauset tribes. The Pilgrims gave him a knife, ring, and bracelet for his friendly advice and information. They also fed him with biscuit, butter, cheese, pudding, roasted duck, and beer, “all of which he liked well.”

The meeting of Governor Carver and Chief Massasoit

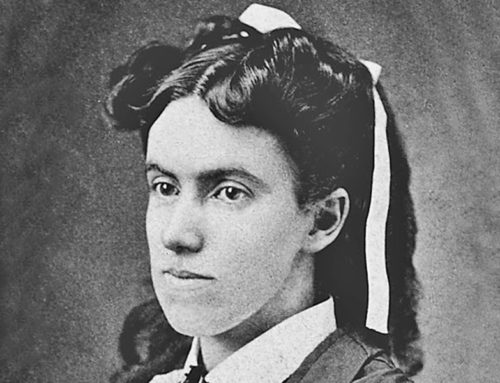

Tisquantum “Squanto” (c. 1585-1622)

The following day, Samoset returned with five more natives carrying furs and returning tools they had earlier stolen from the Englishmen. He informed them that the people the Pilgrims had stolen corn from on their entry into the area were called Nausets, and that they were not kindly disposed to them. A previous expedition into the area by Englishmen had kidnapped twenty or so tribal members. Samoset spent the night with Stephen Hopkins and his family. He promised to return with some of Massasoit’s men and another native who was more fluent in English, a man named Squanto.

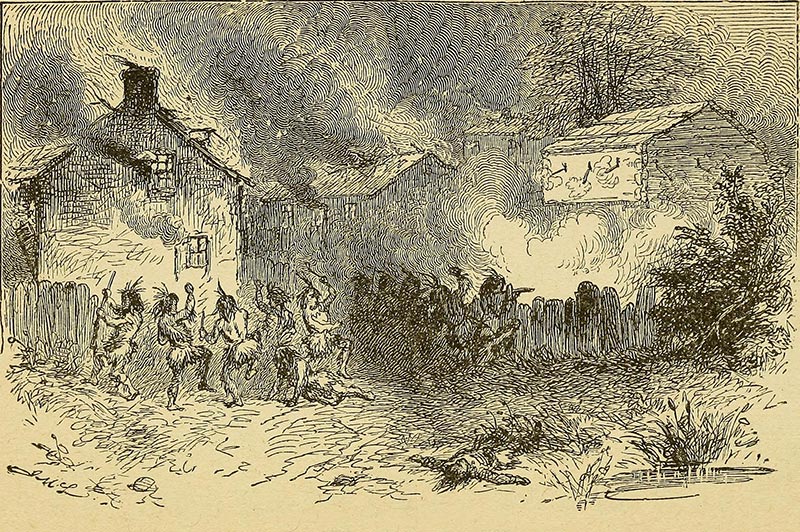

Samoset handed off the diplomatic challenge to Squanto, a man more proficient in English, and a representative for Massasoit, who came the following afternoon to be introduced and exchange gifts. The Englishmen and the Wampanoag Chief agreed to a treaty of mutual defense and trade, which lasted about fifty years. Samoset continued to live as a diplomat the rest of his life, making trade agreements and brokering land deals with settlers. Historians believe he died around 1653, having been the providential first contact with the Pilgrims of Plymouth — a meeting that kept the peace for many years, till Massasoit’s son Metacomet (known as King Philip) declared war on the European interlopers and initiated a bloody conflict. Samoset was providentially placed in the right moment in history to fulfill a task of diplomacy and peace that would have wonderful implications for future generations.

Natives attack the town of Sudbury in 1676 during King Philip’s War