Streight’s Raid Begins, April 21, 1863

“The lot is cast into the lap, but the whole disposing thereof is of the Lord.” —Proverbs 16:33

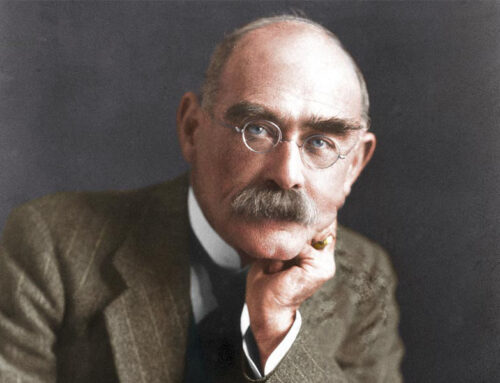

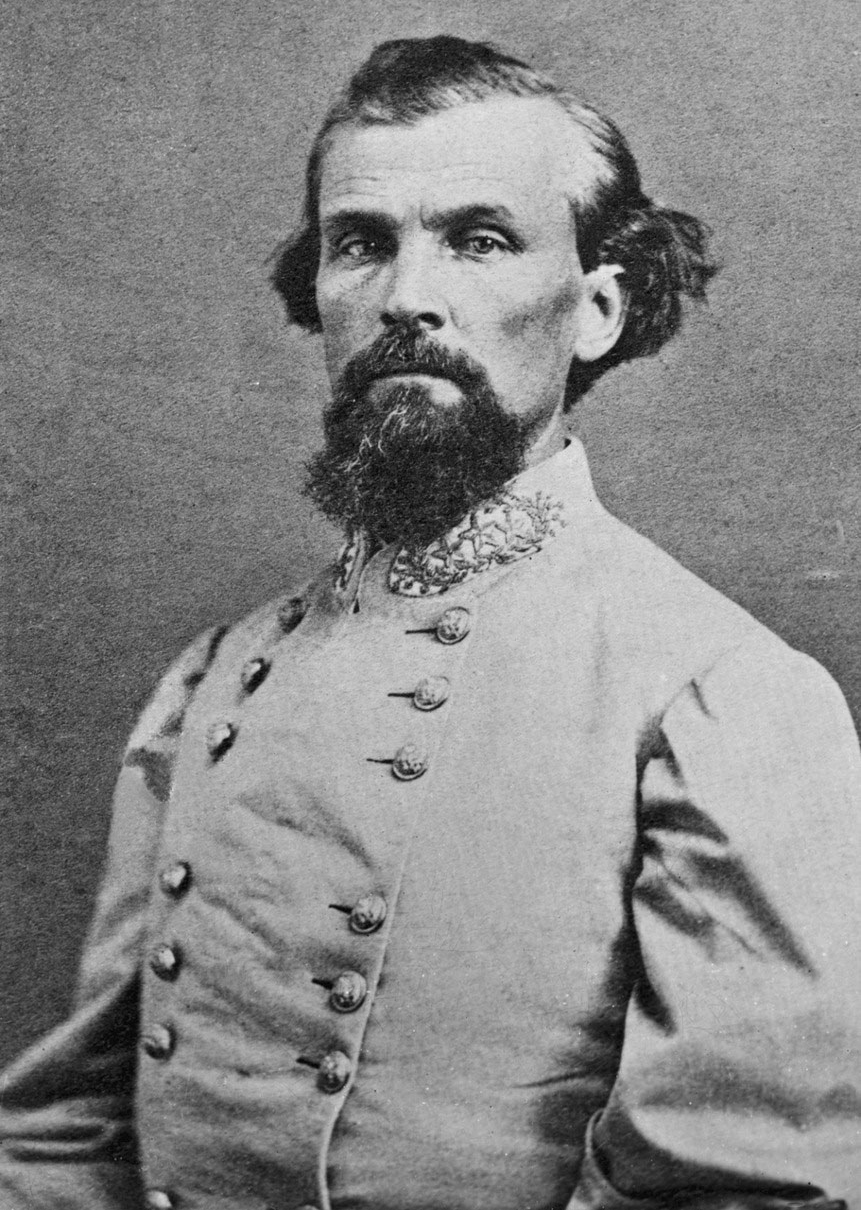

e knew the risks. Union Colonel Abel Streight, “a capable and resourceful officer,” believed he could take 1,700 troopers and raid across north Alabama, destroy the Western and Atlantic Railroad, and finally capture Rome, Georgia. He would be separated from any possible reinforcements and possibly chased by “the greatest cavalry officer ever produced in America,” an “authentic genius” (historian Shelby Foote), “the only cavalry leader I feared” (Grant), and “the man who must be killed if it breaks the treasury and costs ten thousand lives” (Sherman). He became known to the Union high command as “the Devil”—Nathan Bedford Forrest. Abel Streight would go down in the history books as the victim of a clever ruse, and loser of his entire command. Indeed, he would prove unable to out-wit or out-run “the Devil.”

e knew the risks. Union Colonel Abel Streight, “a capable and resourceful officer,” believed he could take 1,700 troopers and raid across north Alabama, destroy the Western and Atlantic Railroad, and finally capture Rome, Georgia. He would be separated from any possible reinforcements and possibly chased by “the greatest cavalry officer ever produced in America,” an “authentic genius” (historian Shelby Foote), “the only cavalry leader I feared” (Grant), and “the man who must be killed if it breaks the treasury and costs ten thousand lives” (Sherman). He became known to the Union high command as “the Devil”—Nathan Bedford Forrest. Abel Streight would go down in the history books as the victim of a clever ruse, and loser of his entire command. Indeed, he would prove unable to out-wit or out-run “the Devil.”

Brig. General Abel Delos Streight, USA (1828–1892)

Lt. General Nathan Bedford Forrest, CSA (1821–1877)

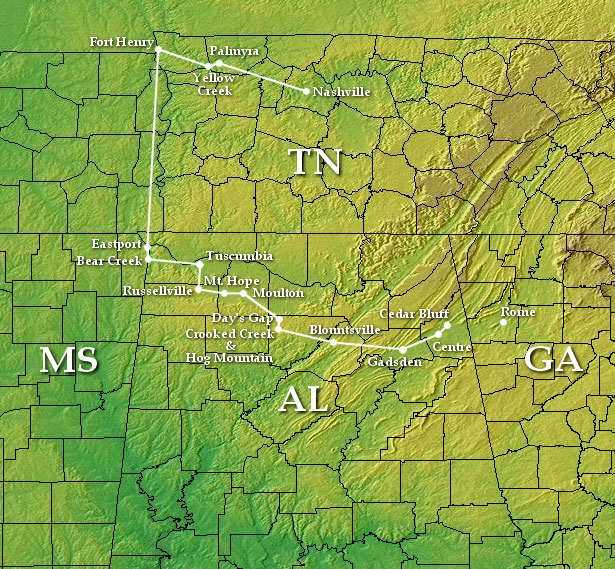

Colonel Streight came up with a bold plan to counteract the embarrassing depredations that Forrest was inflicting on the Union army in Tennessee. He would assemble a command of hand-picked men and conduct what amounted to a one-thousand-mile raid beginning in Nashville, that would cripple the Southern army’s supply lines and wreck their transportation system prior to the next great Union offensive. While Union General Grenville Dodge kept Forrest busy near Corinth, Mississippi, and Grant and Sherman were in the midst of the Vicksburg Campaign, Streight, with seventeen hundred troopers from Tennessee, Alabama, Illinois, Ohio, and Indiana, mounted recalcitrant mules (hence the taunting Confederate label of the “jackass cavalry”) and slipped away from Eastport, Mississippi on April 21, 1863, into their historic raid across northern Alabama.

Major General Grenville Dodge (1831-1916)

General Forrest realized quickly that Streight’s column had moved in an independent direction eastward, and sent scouts to intercept. He mounted his five hundred or so troopers and began a hot pursuit on the flanks of the Federal column. In Cullman County, Alabama near Sand Mountain, the Southern troopers caught up to the Union rearguard and made their first attack. Streight sped up his timetable after the repulse of the Southerners’ assault, foregoing sleep to get further ahead. Forrest leapfrogged his men, allowing some to rest, while detachments “kept up the skeer [scare]” on the tail of the Union expedition.

Map showing the route of Colonel Abel Streight as he made his way towards Rome, Georgia

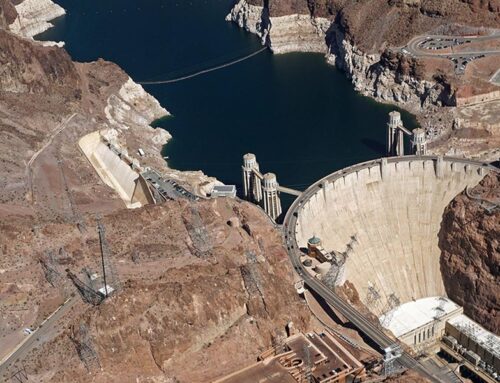

Skirmishes at rural Alabama crossroads and hamlets like Crooked Creek, Hog Mountain, Blountsville, Black Creek, and Blount’s Plantation kept the exhausted Union troopers on the move and turning to fight whenever Forrest’s troopers tried to ambush them or force other confrontations along the way. A messenger was sent by the Southern commander to rouse the people of Rome, Georgia in defense of their town, if the Yankees got that far. The whole town turned out to fortify and prevent the Union vanguard from crossing the Coosa River, which is created by the junction of the Etowah and Oostanaula Rivers at Rome.

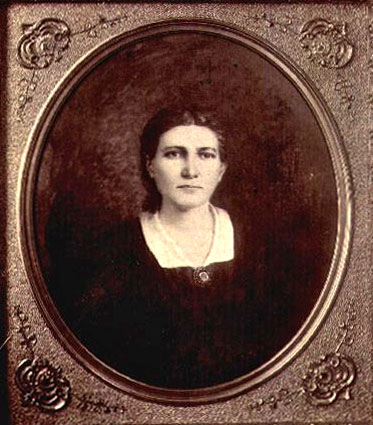

On May 2, Streight burned the wooden bridge across the Black Warrior River, believing he had finally thwarted the pursuit. When Forrest stopped at a home near the crossing and asked if there was a ford that could be used to cross, sixteen-year-old Emma Sansom volunteered to show the General a place she had seen cattle crossing, not too far from the main road. He pulled her up onto the rear of his mount and she pointed the way down stream to the hidden crossing. They came under heavy fire from the Yankees on the other side of the river and several bullets passed through her skirt. She said “they have only wounded my crinoline” and waved her bonnet in defiance. He returned her to her home and left this official note to be treasured all the days of her life:

Emma Sansom (1847–1900), the brave sixteen-year-old Alabama farmgirl who led Forrest and his troops to a nearby ford, enabling their circumvention of the bridge burned by Streight, and the eventual thwarting, surrender and capture of Streight and his troops

Hed Quarters in Sadle

May 2, 1863

My highest regardes to Miss Ema Sanson for hir gallant conduct while my forse was Skirmishing with the Federals across Black Creek near Gadisden, Allabama.

—N.B. Forrest

Brig Genl Comding N. Ala

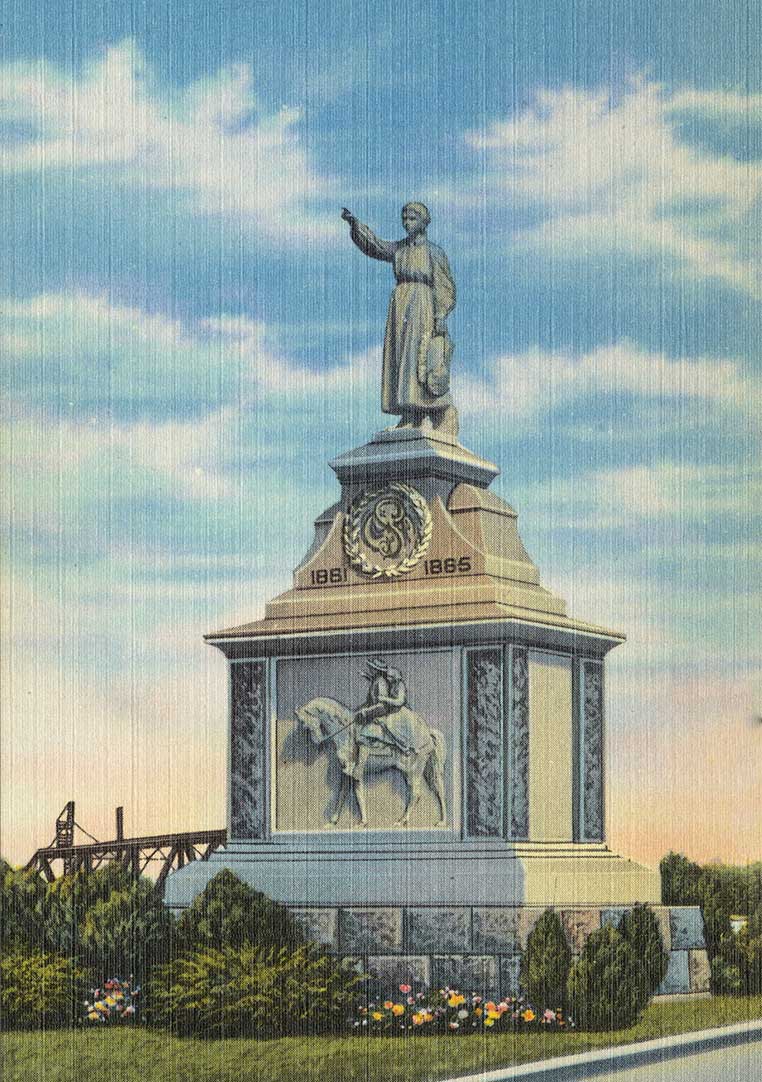

After the war, the state of Alabama presented her with a gold medal commemorating her exploit and awarded her a section of public land “as a testimony of the high appreciation of her services by the people of Alabama.”

The Emma Sansom Monument in Gadsden, AL, depicting Emma pointing out the route, as well as double-mounted behind Forrest

The next day, Forrest rested some of his men and sent the rest to “devil them all night.” Streight lost his race to Rome, for the defenses were manned and the possibility of taking the town made impracticable. On May 3, Colonel Streight stopped twenty miles short of his objective to rest. His men were falling off their mules asleep. Under a flag of truce, Forrest met with his Union counterpart to demand the surrender of his entire command, claiming that the Southern forces outnumbered and surrounded the exhausted raiders. While they stood talking, Forrest’s artillery, only two guns, moved back and forth over his shoulder appearing to be multiple batteries. Streight counted fifteen guns, and Forrest told him that was all that were “able to keep up”! His troopers also moved back and forth as if they were five times their real strength. Colonel Streight gave up and surrendered about sixteen hundred men to Forrest’s four hundred ragged veterans. When Streight realized the trick, he demanded their rifles be returned so they could fight it out. Forrest allegedly offered that “all’s fair in love and war.”

Libby Prison, Richmond, VA, where Streight and his men were sent after their surrender to Forrest on May 3, 1863. After ten months, Streight and 107 other soldiers would escape from Libby Prison by tunnelling from their barracks. Streight was eventually able to cross through enemy territory and, on his return, give a debriefing report to his Union commanders. He was restored to active duty, and later participated in the battles of Franklin and Nashville.

The man who began the war as a private and ended it as a Lieutenant General had bested a formidable and persevering opponent once again. Streight later escaped from prison in the Great Escape from Libby Prison in Richmond and returned to the field against Forrest in the final campaign that ended the war in Alabama, with the Devil’s surrender. As the old Puritan minister John Flavel wrote, “Providence is a mystery, but it always fulfills God’s Will.”

- A Battle From the Start: The Life of Nathan Bedford Forrest by Brian Wills

- Nathan Bedford Forrest: In Search of An Enigma by Eddy W. Davison and Daniel Foxx