“But Jesus knew their thoughts and said to them, ‘every kingdom divided against itself is brought to desolation, and every city or house divided against itself will not stand.’” —Matthew 12:25

Texas Secedes from the Union,

February 1, 1861

![]() ince 1865, secession of states from the United States has been a forbidden subject, discussed only by “Neo-Confederates” and “revanchist cranks”. In recent times, the discussion of breaking from the Union is no longer unthinkable, but part and parcel of a renewed interest in separating from Federal authority. Secession-talk has attracted all sorts of people, from the aging hippies of Vermont to the young independent-minded Texans. Secession discussions and movements are, in fact, an international phenomenon today. In 1861, eleven American states did more than talk and speculate.

ince 1865, secession of states from the United States has been a forbidden subject, discussed only by “Neo-Confederates” and “revanchist cranks”. In recent times, the discussion of breaking from the Union is no longer unthinkable, but part and parcel of a renewed interest in separating from Federal authority. Secession-talk has attracted all sorts of people, from the aging hippies of Vermont to the young independent-minded Texans. Secession discussions and movements are, in fact, an international phenomenon today. In 1861, eleven American states did more than talk and speculate.

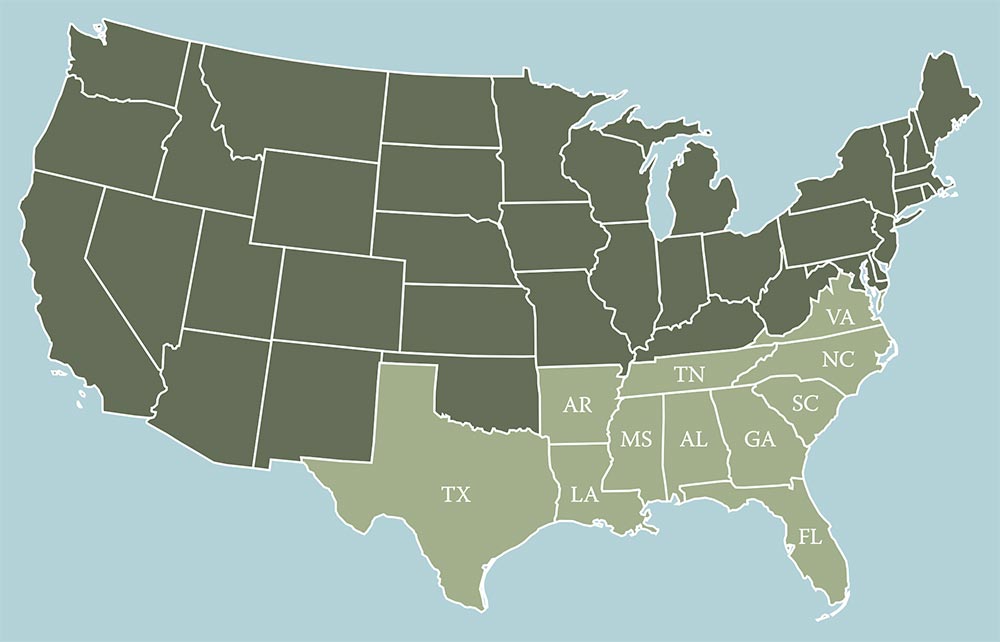

Texas was one of eleven states that seceded from the Union in 1861, including:

South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Virginia, Arkansas, Tennessee and North Carolina

The founding fathers of 1776 spent their time breaking the bonds of empire that had been forged in the colonies since 1607. All thirteen had developed independently of one another and now found themselves dependent on their combined military forces and a Congress determined to maintain both the principles and realities of unity and self-rule. The ultimate result was a republic defined and bounded by a Constitution, and federated state governments. Few of the founders anticipated, and none desired, secession from that union. Nonetheless, disagreements and differences in political philosophy persisted, becoming more obvious in crises which appeared soon after ratification of the Constitution.

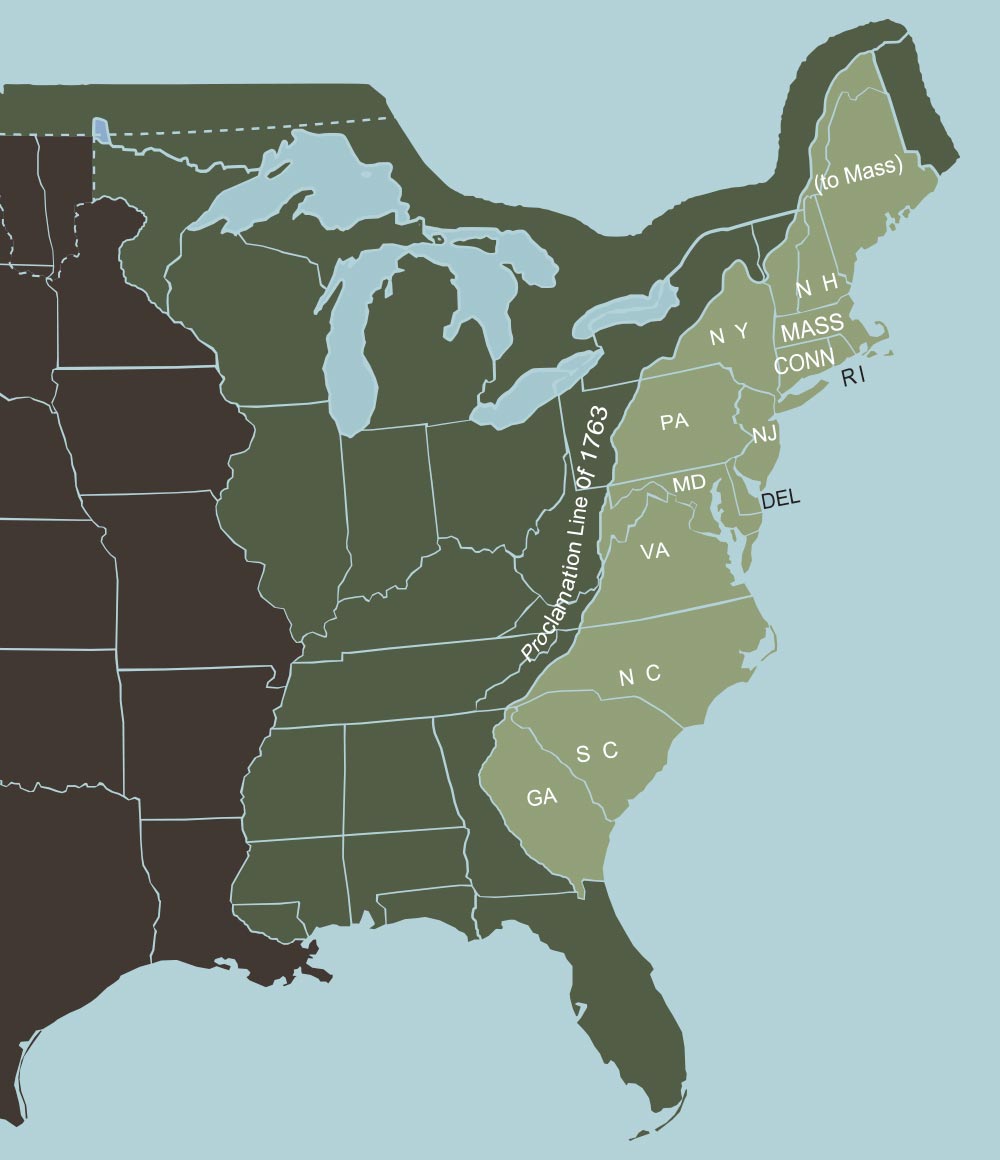

The thirteen original colonies that seceded from Great Britain in 1776 and formed the United States

Talk of secession and serious contemplation of pursuing such a course erupted during the War of 1812 when New Englanders opposed the war, continued to trade with the British enemy, and even met in Convention in Hartford to strategize over resistance to continuing the war. Back-room debate over secession made an appearance. South Carolinians in 1828 during the nullification crisis, suggested they might be better off outside the Union. Again in 1850 political leaders in several states suggested that secession might solve their problem with deadlock in Congress. The breaking point, however, came in late 1860 and early 1861, with the election of a purely sectional, minority President, Abraham Lincoln.

Seal of the Confederate States of America, prominently featuring George Washington

Why seven deep-south states seceded from the Union has been the subject of acrid debate ever since. At the heart of the matter lies the question—could it ever be Constitutional for a state to secede from the United States? The founders did not explicitly put a clause in the document that gives leave to a state to secede. In response to the question, the breakaway states argued that the Central Government had only the rights and powers enumerated in the Constitution. The Tenth Amendment states Powers not delegated to the federal government are reserved to the states and the people. Denying the right of secession is not an enumerated power, therefore, states have the power to secede. Joining the Union was voluntary, which the secessionists believed implied the ability to voluntarily leave it as well. From December 20, 1860 (South Carolina) to February 1, 1861, (Texas), seven southern states seceded from the Union and formed the Confederate States of America.

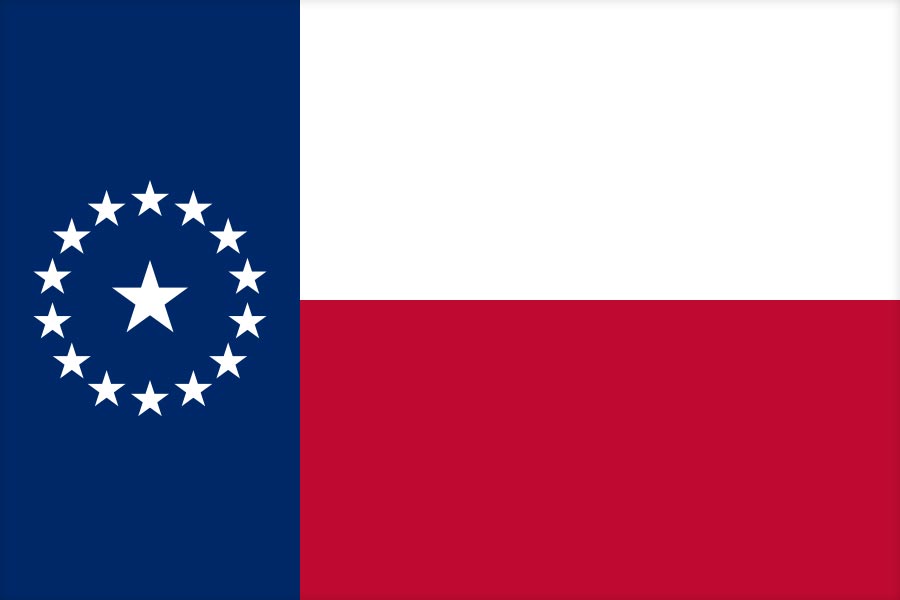

This fifteen-star secession variation of the flag of the Republic of Texas (the design of which was inferred from descriptions as no iterations of this variant exist) was briefly in use in early 1861 between the secession of Texas from the Union and its admittance into the Confederacy

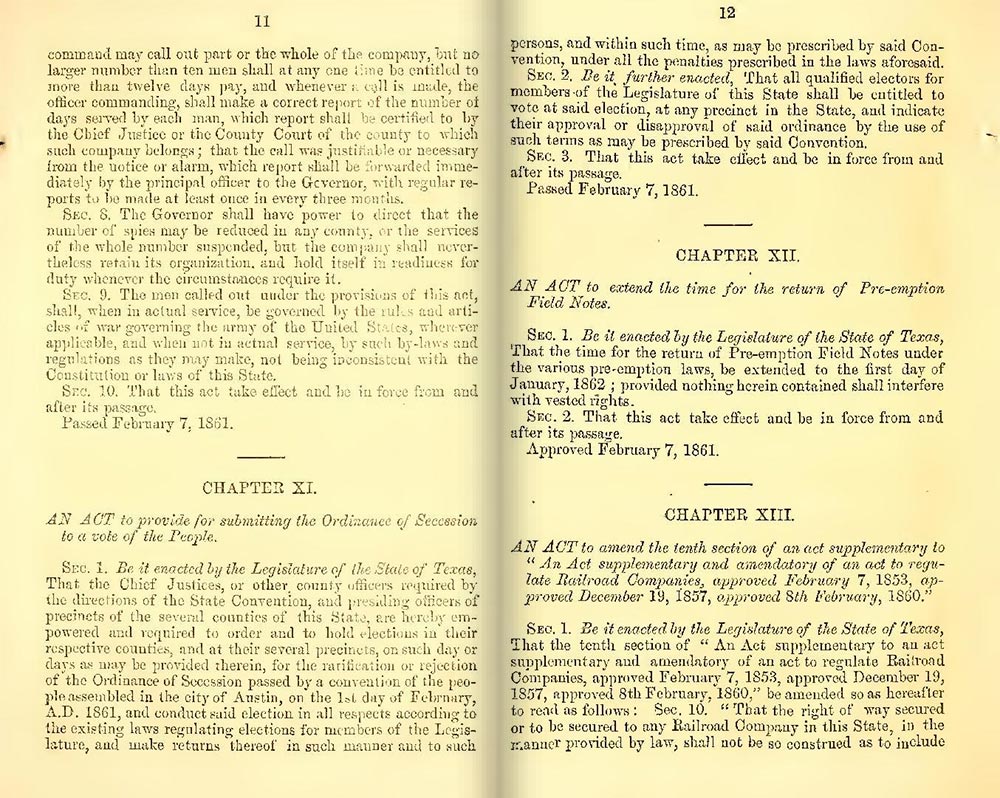

Excerpt from the Laws of the Eighth Legislature of Texas (November 7, 1859 to April 9, 1861), proposing a vote on secession

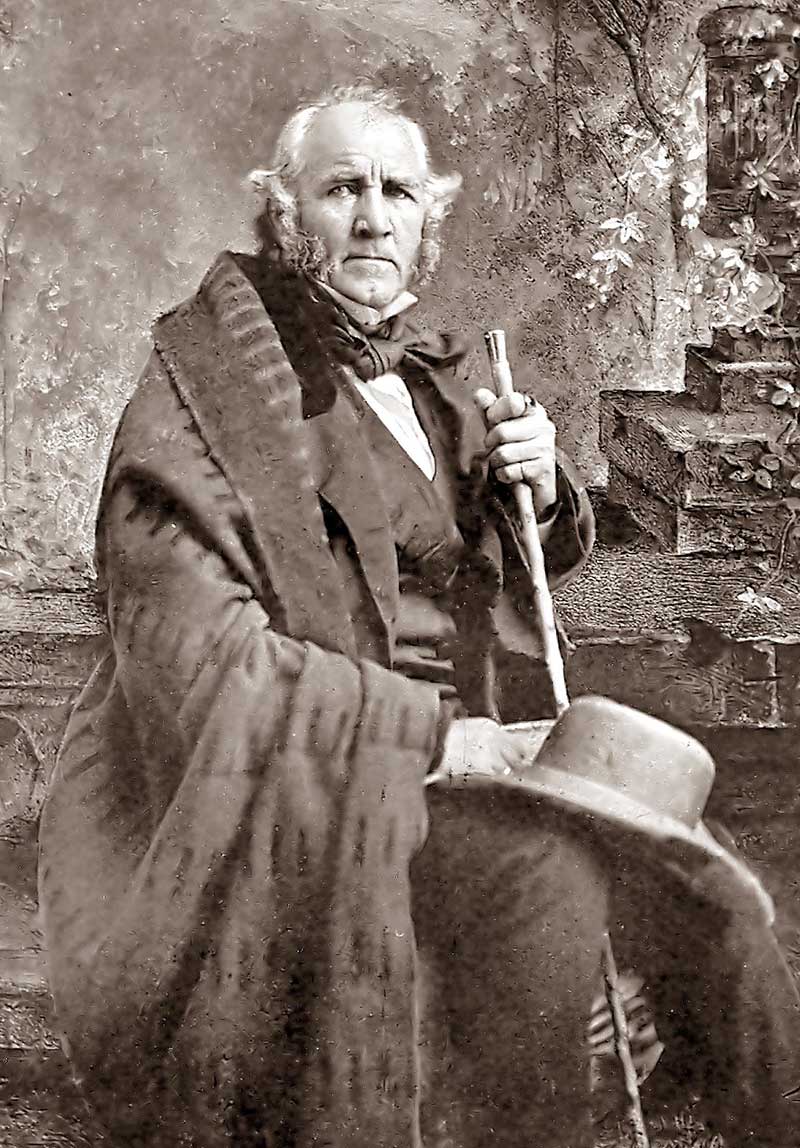

As the other Deep South states left the Union, the Governor of Texas, Sam Houston, took a firm stand against secession, counseling patience and compromise and declaring that the state had no right to break its loyalty to the Union. He refused to call the legislature into session. Texas secessionists, however, many of them legislators, called a convention to address the question, in opposition to Governor Houston. Each county elected two commissioners to attend the convention which met January 28, 1861. They drafted and passed an Ordinance of Secession, 166 to 8, “repealing and annulling” the annexation laws of 1845 which had brought them into the Union.

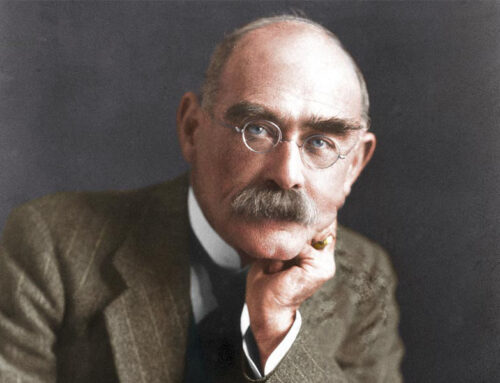

Sam Houston c. 1860 (1793-1863), Governor of Texas at the time of secession, but who opposed leaving the Union. Upon secession, he was deposed and replaced by his Lt. Governor, Edward Clark.

Although Secession was officially announced on February 1, the people of Texas were given the opportunity to accept or reject the Ordinance, a vote in which they approved the actions of the Convention by a large majority. The Convention then reconvened and passed an ordinance joining the Confederate States of America, meeting at their capital city of Montgomery, Alabama. Governor Houston declared the Convention unconstitutional and refused to take an oath to the Confederacy “in the name of my own conscience and manhood,” and was replaced by the Lieutenant Governor. Houston refused to command troops on either side, but finally announced on May 10, he would stand with his beloved Texas and the Confederacy in its war effort. His son Sam Jr., fought for the Confederacy and was wounded at Shiloh. Houston retired to Galveston, corresponded with the new governor during the war, and died at the age of 70 in July of 1863. After the state had seceded, Houston uttered to a Texan crowd in April, these prophetic words:

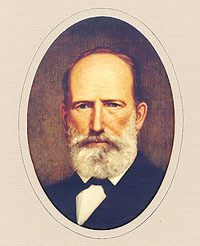

Edward Clark (1815-1880), Lt. Governor of Texas at the time of secession, then promoted to Governor when Sam Houston failed to support secession

“Let me tell you what is coming. After the countless sacrifice of millions of treasure and hundreds of thousands of lives, you may win Southern independence if God be not against you, but I doubt it. I tell you that, while I believe with you in the doctrine of states’ rights, the North is determined to preserve this Union. They are not a fiery impulsive people, as you are, for they live in colder climates. But when they begin to move in a given direction, they move with the steady momentum and perseverance of a mighty avalanche; and what I fear is, they will overwhelm the South.”

First Capitol of the Confederacy, Montgomery, AL, on the occasion of Jefferson Davis’s inauguration as the first and only President of the Confederate States of America, February 18, 1861

- A Constitutional History of Secession, by John Remington Graham

- TexasSecede.com FAQ Page

Image Credits: 1 Map of Confederate States of America (Wikipedia.org) 2 Map of 13 American Colonies (Wikipedia.org) 3 Seal of Confederate States of America (Wikipedia.org) 4 Texas Secession Flag (Wikipedia.org) 5 Eighth Texas Legislature (Wikipedia.org) 6 Sam Houston (Wikipedia.org) 7 Edward Clark (Wikipedia.org) 8 Capitol of the Confederacy (Wikipedia.org)