“Day and night they go around her upon her walls, and iniquity and mischief are in her midst.” —Psalm 55:10

The Battle of Derna and the ‘Shores of Tripoli’, April 27, 1805

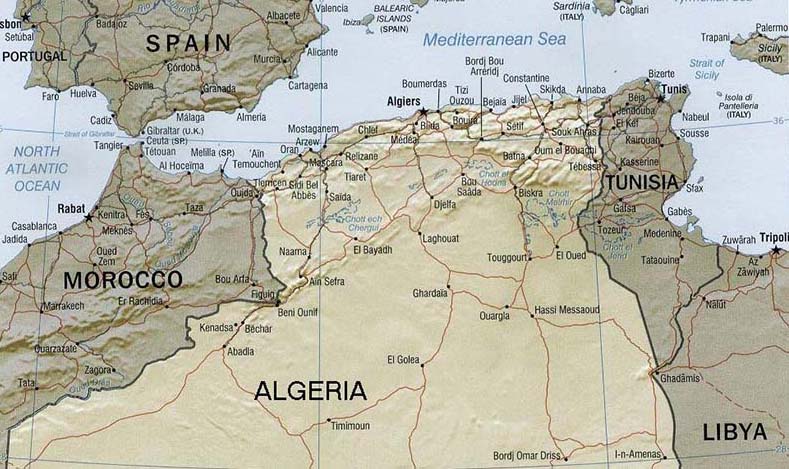

t the beginning of the 19th Century, the most dangerous maritime area in the world lay between Gibraltar and the shores of North Africa, at the narrow entrance to the Mediterranean Sea. The Muslim states of Morocco, Algeria, Tunis and Tripoli formally promoted some of the most successful and brutal incidents of piracy in that era. The Tripolitan pirates became a by-word for the regular destruction of European, Mediterranean, and American shipping in the region. Within a year of independence, American merchants were seized by corsairs of the “Barbary Coast” with demands for ransom of the crews. For the next thirty-three years and every presidency from Washington to Madison, American shipping fell prey to piracy, not just from the Muslim robbers of North Africa but from the three real powers in that part of the world—Britain, France, and Spain. As one historian has rightly written:

t the beginning of the 19th Century, the most dangerous maritime area in the world lay between Gibraltar and the shores of North Africa, at the narrow entrance to the Mediterranean Sea. The Muslim states of Morocco, Algeria, Tunis and Tripoli formally promoted some of the most successful and brutal incidents of piracy in that era. The Tripolitan pirates became a by-word for the regular destruction of European, Mediterranean, and American shipping in the region. Within a year of independence, American merchants were seized by corsairs of the “Barbary Coast” with demands for ransom of the crews. For the next thirty-three years and every presidency from Washington to Madison, American shipping fell prey to piracy, not just from the Muslim robbers of North Africa but from the three real powers in that part of the world—Britain, France, and Spain. As one historian has rightly written:

“The Moroccan and Algerine captures in the 1780s exposed the United States as a weak confederation of minor, jealous states that had neither the will nor the power nor the treasury to protect its merchant ships.”[1]

Within twenty-five years, retaliation by the United States reached its tipping point with the capture by Marines of the Pirate city of Derna.

Barbary Coast of North Africa

With his election to the presidency in 1800, Thomas Jefferson hoped to end the Federalist policy of paying off the bashaws of North Africa in order to trade in the Mediterranean. Now that the country possessed a fleet of frigates with sailors experienced and battle-hardened from the “Quasi-War” with France, Jefferson’s Secretary of State James Madison notified the American diplomats in North Africa that the U.S. would no longer pay tributes for trade privileges. Tripoli declared war on the United States.

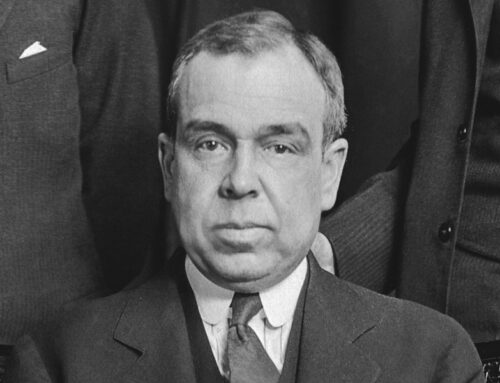

Stephen Decatur, Jr. (1779-1820)

The Americans sent a naval squadron to the waters off Tripoli and declared a blockade. In the brinkmanship that ensued between American ships and the pirates, both sides experienced victories and defeats. The USS Philadelphia was run aground and captured. Stephen Decatur conducted a raid into the harbor and burned the ship under the noses of the city defenses. A sortie by American gunboats captured or sank four enemy gunboats. The bashaw was impressed but not overawed, and the stalemate over the capital city continued, as did the pirates scooting in and out of north African ports.

Burning of the USS Philadelphia in the harbor of Tripoli on February 16, 1804

President Jefferson, in 1804, authorized three individuals to work in concert to bring the war to closure. William Eaton, former American consul in Tunis and an ex-Army captain, was given authority to link up with the forces of Hamet Karamanli, the brother of the bashaw of Tripoli, Yusuf, and organize a land attack on the City of Derna. The United States would back Hamet as the legitimate ruler of Tripoli in return for American captives, cash, and free trade. At the same time, Tobias Lear was given full authority to negotiate a Treaty of Peace with Yusuf, the Bashaw of Tripoli, and Commodore Samuel Barron in charge of the American naval forces was to continue the blockade of ports and hold overall command.

William Eaton (1764-1811)

Isaac Hull (1773-1843)

Eaton met up with Hamet in Alexandria, Egypt. It was agreed that Eaton would be in overall command of not just his force of eight Marines and two Navy midshipmen, but also the five hundred or so Arab freebooters collected by Hamet. The bizarre little army marched five hundred miles across the Libyan desert to the walls of Derna. The Arabs revolted several times, the expedition ran out of food, but the undisciplined mob nonetheless took positions for storming the city. On April 27, 1805, Captain Hull got three of his navy ships close enough to bombard the walls of the city, while the eight Marines and Captain Eaton attacked that side of the fortifications, when the defenders retreated. Lieutenant Presley O’Bannon “hauled down the enemy’s flag and planted the American ensign on the walls of the battery.” One Marine was killed and two wounded, with Hamet’s forces on the opposite side of the city losing ten men. The walled city of Derna was now the possession of the United States and a would-be new bashaw.

Presley Neville O’Bannon (1776-1850)

Battle for Derna

Unknown to the indefatigable and persevering Eaton, one of the greatest American military exploits of all times by just a tiny handful of U.S. Marines, had been overruled by a deal that Tobias Lear had struck in Tripoli with Yusuf Karamanli, to release American prisoners (for a hefty price), remain in power, and end depredations against American merchant shipping. Derna was returned to the pirates, Hamet did not get the throne, but his family was returned to him by his brother. Eaton received a nice pat on the back for his heroic efforts, Jefferson happily accepted the treaty made by Lear, and the war ended for the time being. An uneasy peace prevailed till 1815, when the United States fought the “Algerine War,” putting a final end to the military scraps with Barbary pirates. In short order, France and Spain conquered North Africa and the former piratical states remained in thrall until the 1950s.

Stephen Decatur boarding a Tripolitan gunboat during a naval engagement

William Eaton’s fantastic efforts were at least remembered in the Marine Corps Hymn:

“From the Halls of Montezuma to the shores of Tripoli…”

The irrational and compromising American foreign policy and its accompanying diplomatic blunders and military disasters did not fade away with the payments of bribes and under-the-table deals, made with the pirates of the Barbary shores in the early 19th Century.