“As for you, you meant evil against me, but God meant it for good…” —Genesis 15:20

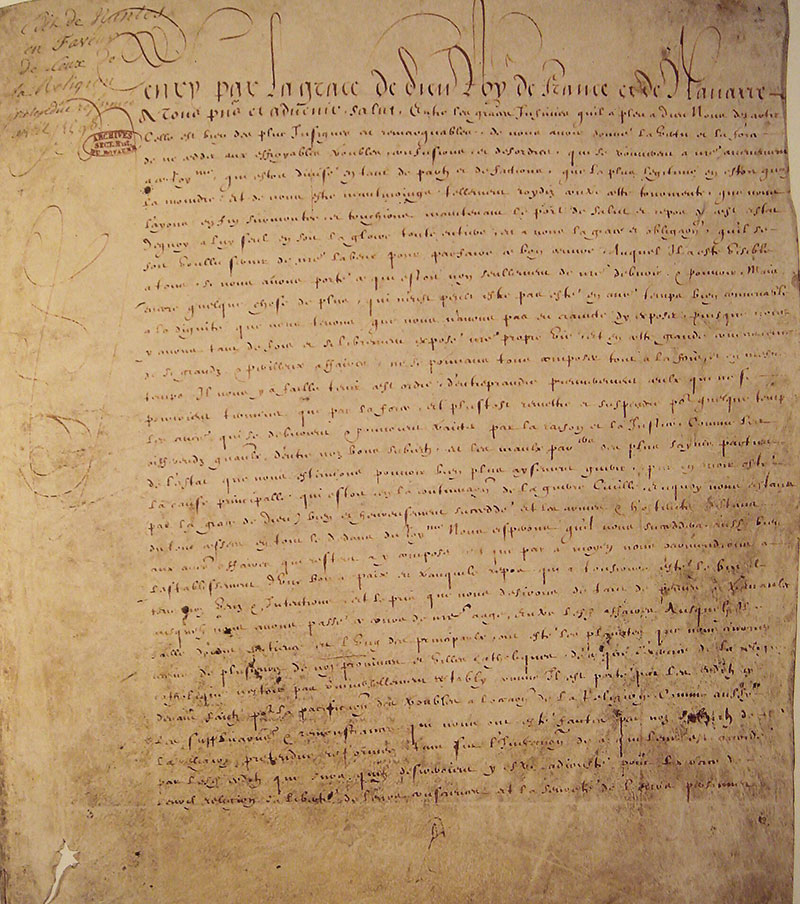

The Edict of Nantes Proclaimed, April 13, 1598

![]() everal of the greatest preachers, evangelists and theologians of the Protestant Reformation were born in France, often writing in French as well as Latin. They pastored churches in France or Switzerland, and trained the men who led the Reformation in their homeland. Jacques Lefevre d’Etaples, Jean Calvin, Pierre Viret, Gauillaume Farel, and others, proclaimed the Gospel in those early and middle years of the Reformation in France, and trained like-minded men to take the truth to every corner of their country and the world. Calling all people to repentance, and salvation by faith alone, and the restoration of New Testament Christianity based solely on the Word of God, these men were used of God to bring multiple thousands to saving faith and the establishment of “Reformed” Churches across France. The members of those congregations were called Huguenots.

everal of the greatest preachers, evangelists and theologians of the Protestant Reformation were born in France, often writing in French as well as Latin. They pastored churches in France or Switzerland, and trained the men who led the Reformation in their homeland. Jacques Lefevre d’Etaples, Jean Calvin, Pierre Viret, Gauillaume Farel, and others, proclaimed the Gospel in those early and middle years of the Reformation in France, and trained like-minded men to take the truth to every corner of their country and the world. Calling all people to repentance, and salvation by faith alone, and the restoration of New Testament Christianity based solely on the Word of God, these men were used of God to bring multiple thousands to saving faith and the establishment of “Reformed” Churches across France. The members of those congregations were called Huguenots.

The Edict of Nantes was signed in April 1598 by King Henry IV and granted the Calvinist Protestants of France—also known as Huguenots—substantial rights in the nation, which was in essence completely Catholic

The political regimes of France owed total ecclesiastical allegiance to the Roman Catholic Church, requiring loyalty to that communion from all who would hold office, especially the King. What had started as a reform movement in that Church had become a separatist revival of Biblical Christianity, rejecting much church tradition and the authority of unbiblical church hierarchies. The Roman bishops, including the Pope, declared the Huguenots heretics and schismatics, but the adherents to Protestant, especially “Calvinist” theology, established the Reformed French Church and suffered the consequences of defying Rome.

Admiral Gaspard de Coligny (1519-1572)

King Charles IX of France (1550-1574)

The Church in Geneva, Switzerland, under the wise direction of Calvin and Viret helped organize the French Reformed Church. As converts increased, so did the attacks by the Roman Catholic Church and their adherents close to the royal court. The massacre of Protestants at Vassy triggered a series of eight “French Wars of Religion” beginning in 1562 and lasting to 1629. Massacres of Protestants took place in a number of cities in France, until an effective military resistance was formed, and the Protestants fought back to defend their families and property. The paramount leader of the Huguenots was the Admiral of France, Gaspard de Coligny. A seemingly endless series of bloody wars followed the template of the French government hiring armies of mercenaries, who occasionally won but couldn’t be paid on time. A truce would be signed, the soldiers cut loose to fend for themselves, another treaty signed. In 1572 a cabal of Catholic conspirators assassinated Coligny and murdered hundreds of Protestants in Paris under a safe-conduct pass from King Charles IX, who died two years later. The wars resumed under King Henry III for the fifteen years of his reign, until his assassination by a Dominican Friar.

The St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre, which lasted several weeks in 1572, resulted in the deaths of anywhere from 5,000 to 30,000 Huguenots at the hands of the Catholics

The throne then came to Henry of Navarre, a Protestant, who converted to Roman Catholicism to become King Henry IV, the first of the line of Bourbon monarchs of France. In 1598, to unite the Kingdom and terminate the seemingly endless wars against the Huguenots, The Edict of Nantes was issued on April 13th, granting a measure of religious freedom to the French Protestants and concomitant political freedoms as well. The truce was an uneasy one, for the Catholic Church still determined to exterminate the Protestants, caused occasional fighting and retaking of Calvinist strongholds in the country. Henry escaped several attempted assassinations by Catholic factions until they finally murdered him in 1610. The new king, Louis XIII, renewed fighting against the Huguenots until only two towns were still held by the Protestants, La Rochelle and Montauban. They were eventually taken by siege, and the Edict partially restored in the aftermath.

King Henry IV of France (1553-1610)

Louis XIII of France (1601-1643)

The grandson of Henry IV, Louis XIV moved strongly against the Protestants and the Edict was revoked in 1685 making all Protestants in France outlaws unless they convert to Roman Catholicism. Hundreds of thousands Huguenots emigrated, mostly people of substance, skills, and education, to America, England, Holland, Germany, South Africa and other places. Wherever they went, those Reformed Protestants enriched the culture and prosperity of their new countries. In American, they especially settled in South Carolina and Virginia, and their children and grandchildren would play key roles in the American War for Independence and the early Republic. Although their relative percentage of the population remained small, the French Protestant heritage in the United States is a reminder that what the “Sun King” in his depraved and senseless revocation of the Edict of Nantes meant for evil, God intended for good in a new land of freedom and liberty.

King Louis XIV of France, the “Sun King” (1638-1715)

The French Huguenot Church in Charleston, SC—which can trace its origins back to a group of 45 Huguenots who arrived in Charleston in April 1680—is one of the stops on

Landmark Events’ Charleston & Savannah Tour next week!

With their old-world charm and blend of Old South, French and Victorian cultures, Charleston & Savannah are among the most transporting and inspiring cities for studying the providence of God and the souls that called this area home. Join us there next week, April 19-23! Learn More >

- For further study read: The Huguenots, or Reformed French Church by William Henry Foote, 1870; reprinted by Sprinkle Publications, 2002.

Image Credits: 1 Edict of Nantes (Wikipedia.org) 2 Admiral Gaspard de Coligny (Wikipedia.org) 3 King Charles IX of France (Wikipedia.org) 4 King Henry IV of France (Wikipedia.org) 5 King Louis XIII of France (Wikipedia.org) 6 St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre (Wikipedia.org) 7 King Louis XIV of France (Wikipedia.org) 8 French Huguenot Church (Wikipedia.org)