“How good and pleasant it is when brothers live together in unity!” —Psalm 133:1

General Robert E. Lee’s

Surrender at Appomattox, April 9, 1865

pril is Confederate History Month in six Southern states. Four states commemorate a “Confederate Memorial Day.” And what a month it was for the four years of independence, 1861-1865. A Union fleet tried to reinforce and supply Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor, initiating the shelling of the Fort by CSA forces on the April 6, 1861; one of the bloodiest and most horrifying battles in American history occurred at Shiloh in Tennessee in April 1862; and General Robert E. Lee surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia on April 9, 1865, signaling the end of the war to all the other armies still in the field.

pril is Confederate History Month in six Southern states. Four states commemorate a “Confederate Memorial Day.” And what a month it was for the four years of independence, 1861-1865. A Union fleet tried to reinforce and supply Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor, initiating the shelling of the Fort by CSA forces on the April 6, 1861; one of the bloodiest and most horrifying battles in American history occurred at Shiloh in Tennessee in April 1862; and General Robert E. Lee surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia on April 9, 1865, signaling the end of the war to all the other armies still in the field.

General U.S. Grant (seated, left) accepts the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia from General Robert E. Lee (seated, right) in the parlor of Wilmer McLean at Appomattox Court House, VA, April 9, 1865

That last tragic event was the culmination of the “Overland Campaign” and the subsequent siege of the strategic City of Petersburg, Virginia, conducted by Union General Ulysses S. Grant over the final year of America’s War Between the States. President Abraham Lincoln had promoted General Grant to command of all the Union armies, for he had proven the one fighting general who understood the President’s strategic plan—destroy the Confederate armies and break the will of the populace to continue their Constitutional bid to separate from the Union. Grant’s willingness to expend any amount of blood to achieve the goal of military victory, and to allow any measures against the civilian population of the South to break their will to resist the Federal government, ultimately proved successful and lauded by the “court historians” ever since.

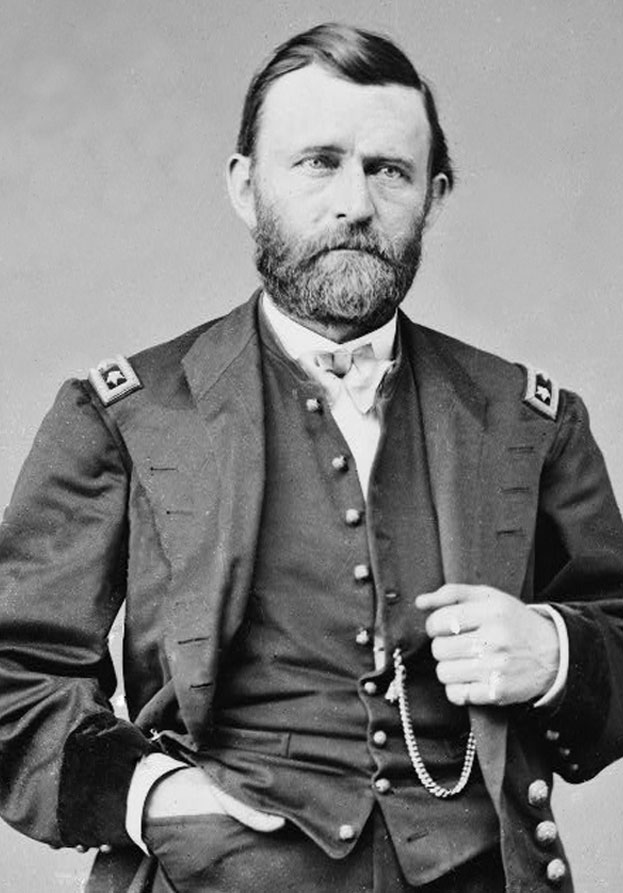

General U.S. Grant (1822-1885),

Union Commander

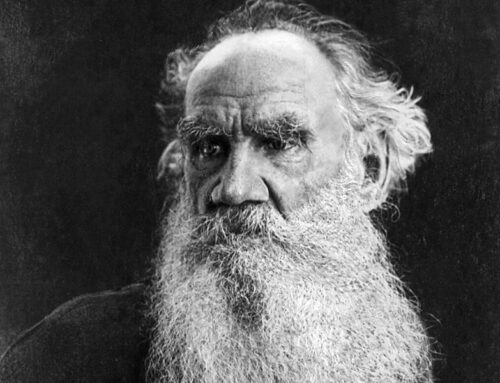

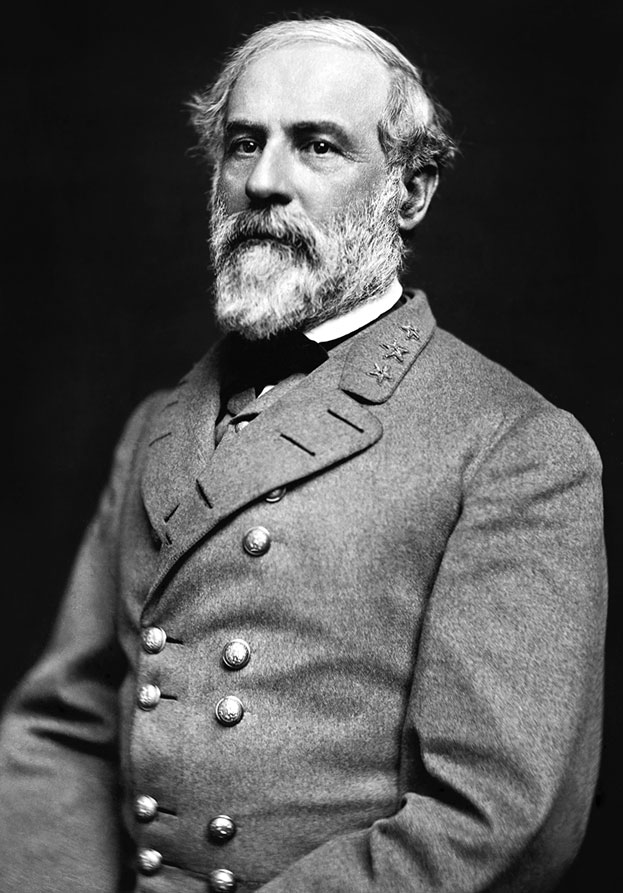

General Robert E. Lee (1807-1870),

Confederate Commander

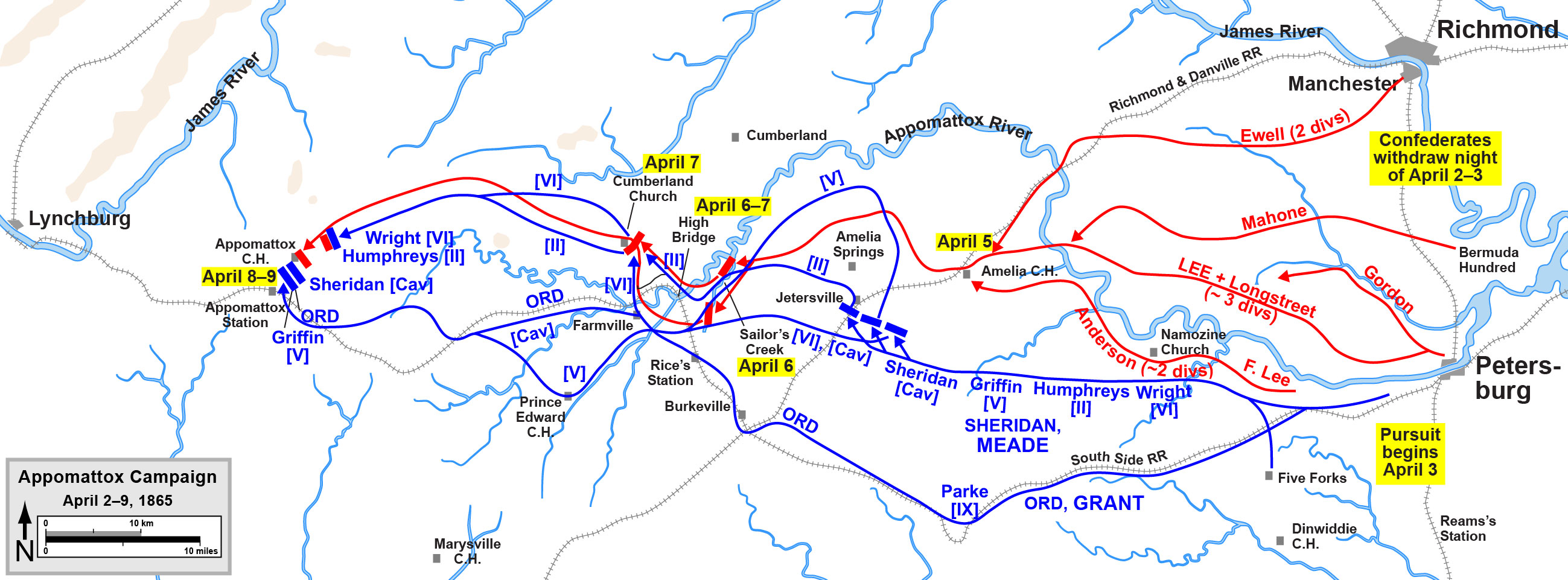

Grant realized the priority of grinding down the Confederate Army in Virginia, led by Robert E. Lee, the South’s most successful General. With “overwhelming numbers and resources” the Yankee commander finally breached the Confederate defenses of Petersburg on April 2, 1865, after a brutal nine-month siege. As the hungry Confederate survivors streamed from their forty miles of trenches westward to meet up with food supplies, President Jefferson Davis and the government of the Confederacy fled the capital city of Richmond, to try and carry on the war from points further south. In close pursuit of Lee’s army, the Union forces scooped up thousands of demoralized and footsore men who would not or could not go any further.

The respective troop movements in the final days before Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Court House (left side of map), April 2-9, 1865. Union troops are indicated by blue, while Confederate troops are indicated by red.

Union cavalry interposed between Lee’s army and the rations that had been sent for rendezvous with the starving army at a key railroad junction. Forced on to backroads moving westward toward Lynchburg, Confederates trudged on for twenty-four hours straight with the Union army following a trail of abandoned and burned wagons and the flotsam and jetsam of equipment and broken down soldiers. On April 6, Union cavalry, moving fast, blocked CSA General Ewell’s Corps at Sailor’s Creek until the infantry arrived. Several thousand men fell on both sides in a ferocious battle, and 7,000 Confederate troops were surrounded and captured, along with the wagon train.

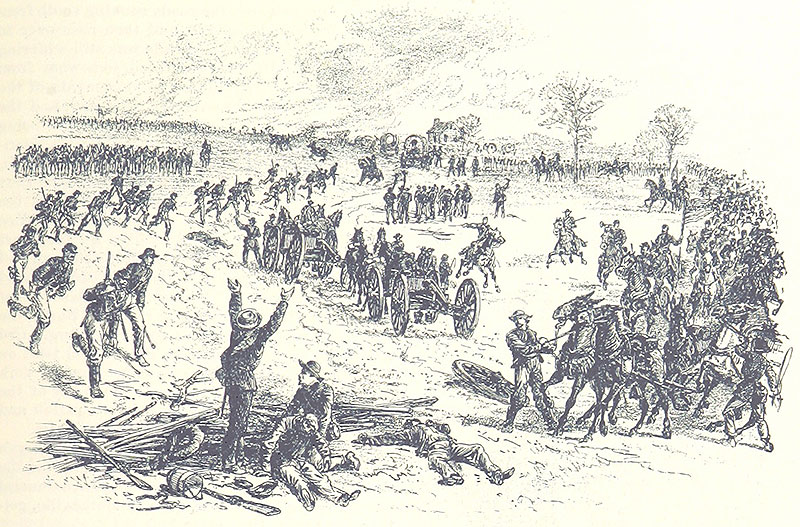

During the Appomattox Campaign, Union cavalry captures Confederate guns and burns a wagon train near Paineville, Virginia, April 5, 1865

By April 8, the remnants of Lee’s army arrived in the environs of the little crossroads village of Appomattox Court House. He could probably have placed only about 10,000 rifles into a battle line with another 2,000 or so officers and perhaps another 10,000 artillerymen without guns, sailors, soldiers who had no weapons, wagoners, surgeons, chaplains and other basically unarmed stragglers and other non-combatants. More than 30,000 superbly-armed infantry under General Meade filed into place behind and on the flanks, with another 30,000 under Sheridan, many of them cavalry, arrived in Lee’s front, and moved to complete the total envelopment, before the gray army could break through to Lynchburg, twenty miles away.

Appomattox Court House National Historical Park, showing the historic Court House on the left, and a reconstruction of the McLean House on the right

Corps commander General John B. Gordon sent a faithful remnant of tough Confederate infantry and cavalry to open a path for the rest of the army. Initial success against Union cavalry quickly stalled when Union infantry showed up to seal the breach, and the Army of Northern Virginia was trapped. General Lee sent a courier into Union lines to arrange a conference with General Grant to surrender the Southern forces. Confederate Staff Officer Colonel Walter Marshall rode ahead to locate a suitable meeting place, and secured the comfortable home of Wilmer McLean near Appomattox Court House. The opposing generals met in the parlor, General Lee bringing only Colonel Marshall, and General Grant with Generals Ord and Sheridan, and Union staff officers of unknown number. After some small talk of the old army, the two men worked out what Lee considered very generous terms, and exited the home. The Yankee officers offered McLean money for some of the furniture, then stole the rest, including a child’s rag doll on the floor.

Wilmer McLean (1814-1882) was a Virginia grocer and businessman who moved his family away from Manassas, VA in 1861 to get away from the war, only to have the war follow him to his new home in quiet Appomattox Court House, VA where he served as the reluctant host of Lee’s surrender to Grant in 1865

A panoramic image of the reconstructed parlor at McLean House, exactly as it appeared in April, 1865. Lee was seated at the marble-topped table shown at the left, while Grant was seated at the wood desk shown on the right. All furnishings are exact replicas copied from extant pieces in various historic collections.

The most destructive and consequential war in American history had, for all practical purposes, come to an end with the surrender of the most important Confederate army. General Lee went on to become the President of Washington College in Lexington, Virginia, renamed Washington and Lee after his death in 1870. General Grant went on to serve two terms as United States President, his second one ending in scandal. Appomattox today advertises their town motto “Where our Nation Reunited.” The generation that slaughtered each other disagreed over the meaning of the Constitution. Over what can the “nation” unite, now that that document is a “dead letter of white supremacy” and history is a meaningless waste of time, to be destroyed and sent down the memory hole into the fires of Orwell’s Ministry of Truth? Is there a way to heal this divided country? There is, and it’s as old as time. The Gospel of Christ Jesus—it is the only means of salvation for the sinner, and the nation

The McLean House as photographed in April of 1865, about the time that it hosted the historical surrender of Lee to Grant

- A Place Called Appomattox by William Marvel (UNC Press, 2000)

- Lee’s Farewell Address to the Army of Northern Virginia

Image Credits: 1 Lee’s Surrender to Grant (Wikipedia.org) 2 U.S. Grant (Wikipedia.org) 3 R.E. Lee (Wikipedia.org) 4 Map (Wikipedia.org) 5 Capture (Wikipedia.org) 6 Appomattox Court House (Wikipedia.org) 7 Wilmer McLean (Wikipedia.org) 8 McLean Parlor (Wikipedia.org) 9 McLean House (Wikipedia.org)

Image Credits: 1 Putin at age 8 (Wikipedia.org) 2 Leningrad, 1941 (Wikipedia.org) 3 KGB (Wikipedia.org) 4 Wall of Grief (Wikipedia.org) 5 Federal Security Service (Wikipedia.org) 6 Yeltsin resignation (Wikipedia.org) 7 Putin inauguration (Wikipedia.org) 8 Christmas service (Wikipedia.org) 9 Official portrait (Wikipedia.org)