“They that go down to the sea in ships, that do business in great waters.” —Psalm 107:23

The Final Sinking of the CSS Hunley,

February 17, 1864

bumper sticker I observed in Charleston, South Carolina a number of years ago read: “There are only two kinds of ships: submarines and targets.” How appropriate to see that sign in Charleston, for it was there that the H.L. Hunley became the first submarine in world history to sink an enemy vessel in combat. The Hunley crew carried with them the esprit that came to characterize undersea warriors of all ocean-going nations thereafter. In the Second World War, American and German submarines totaled more than 4,000 ships sunk and more than twenty million tons of shipping. As in many cases of technological breakthroughs, several men pooled their ideas and resources, and through the exigencies of Providence, produced the working product. In this particular experiment, Horace Lawson Hunley stewarded the building of a new weapon to challenge Yankee naval supremacy through to its end.

bumper sticker I observed in Charleston, South Carolina a number of years ago read: “There are only two kinds of ships: submarines and targets.” How appropriate to see that sign in Charleston, for it was there that the H.L. Hunley became the first submarine in world history to sink an enemy vessel in combat. The Hunley crew carried with them the esprit that came to characterize undersea warriors of all ocean-going nations thereafter. In the Second World War, American and German submarines totaled more than 4,000 ships sunk and more than twenty million tons of shipping. As in many cases of technological breakthroughs, several men pooled their ideas and resources, and through the exigencies of Providence, produced the working product. In this particular experiment, Horace Lawson Hunley stewarded the building of a new weapon to challenge Yankee naval supremacy through to its end.

An 1863 illustration of the CSS Hunley in Charleston Harbor, with H.L. Hunley depicted as the sentinel, and also showing Sullivan’s Island and a dispatch boat in the background

An 1863 illustration of the CSS Hunley in Charleston Harbor, with H.L. Hunley depicted as the sentinel, and also showing Sullivan’s Island and a dispatch boat in the background

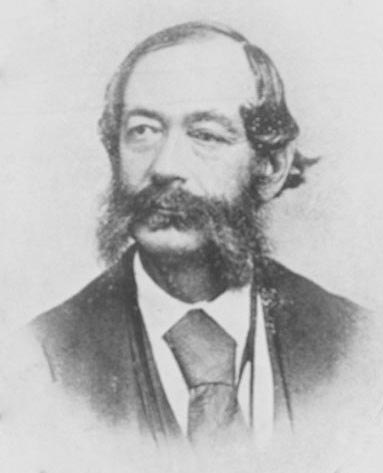

Hunley was a thirty-seven-year-old attorney and plantation owner, toiling as the assistant customs collector in the Custom House on Canal Street in New Orleans when Louisiana seceded from the Union. In the following months and years, the Union blockaders of the 3,500-mile coastline of the Confederacy increased daily in numbers and efficiency. The South’s largest city by far with well over 100,000 people (including 10,000 free blacks and 13,000 slaves), New Orleans sensed their vulnerability from the Union Gulf Squadrons about a hundred miles away and a few hours’ trip up the Mississippi River.

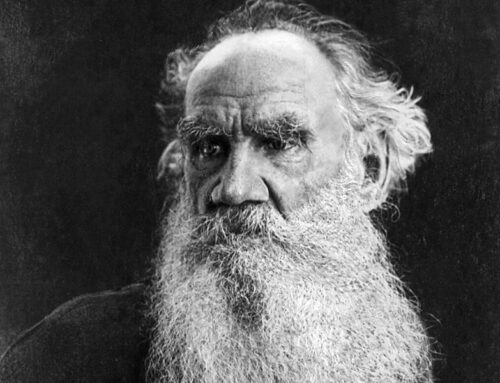

Horace Lawson Hunley (1823-1863)

Charleston Harbor as it would have appeared in 1863

After taking a small blockade runner from New Orleans to Cuba and back, Hunley’s free-enterprise entrepreneurship led to a partnership with two other men who owned a machine shop and had a government contract to make bullets. However, McClintock and Watson shared a passion for profit and privateering. They agreed to design and build a submarine to prey on Yankee shipping. Hunley brought “vision, business acumen, and potential investors” to the project. McClintock brought “engineering experience and the sheer joy of tinkering.” They had to keep the machine a closely held secret. In late April of 1862, their prototype submarine, dubbed Pioneer, was scuttled by the three partners to avoid capture when Union Admiral David Farragut, along with an Army contingent, seized New Orleans. Hunley moved the submarine building operation to Mobile, Alabama, the only major Confederate port still open in the Gulf.

A full-scale replica of the Pioneer, the prototype submarine built by Hunley, McClintock and Watson before their design of the CSS Hunley

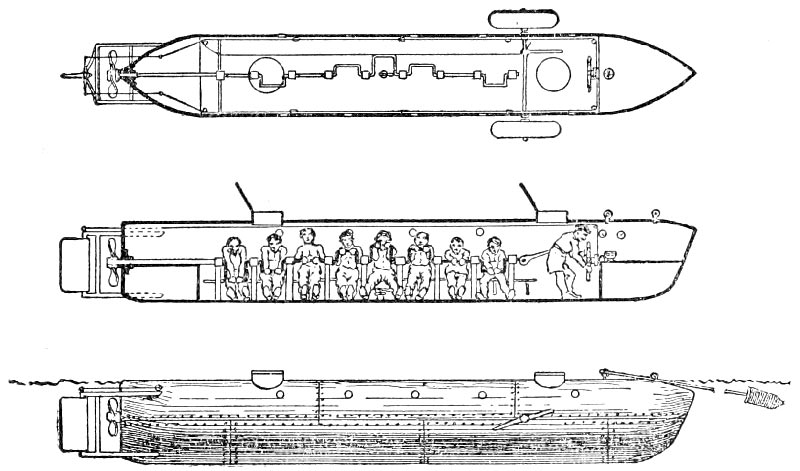

Overcoming inter-service rivalries, government opposition, and starting a manufacturing concern from scratch in a competitive and sometimes hostile environment, the partners—with the full approval of the new commander in the city, Dabney Maury, Virginia-born nephew of the famous “pathfinder of the seas,” Matthew F. Maury—secured a factory, equipment, and clever and competent new engineering team members. A second boat was therein constructed, but failed in its sea trials in Mobile Bay. The third submarine built by the consortium and eventually named the H. L. Hunley was forty feet long and four feet high at midship. It required seven crewmen sitting on a plank and pumping a zig-zag crank that turned a differential, screw propeller. The captain sat at one end steering and directing the boat’s rudder.

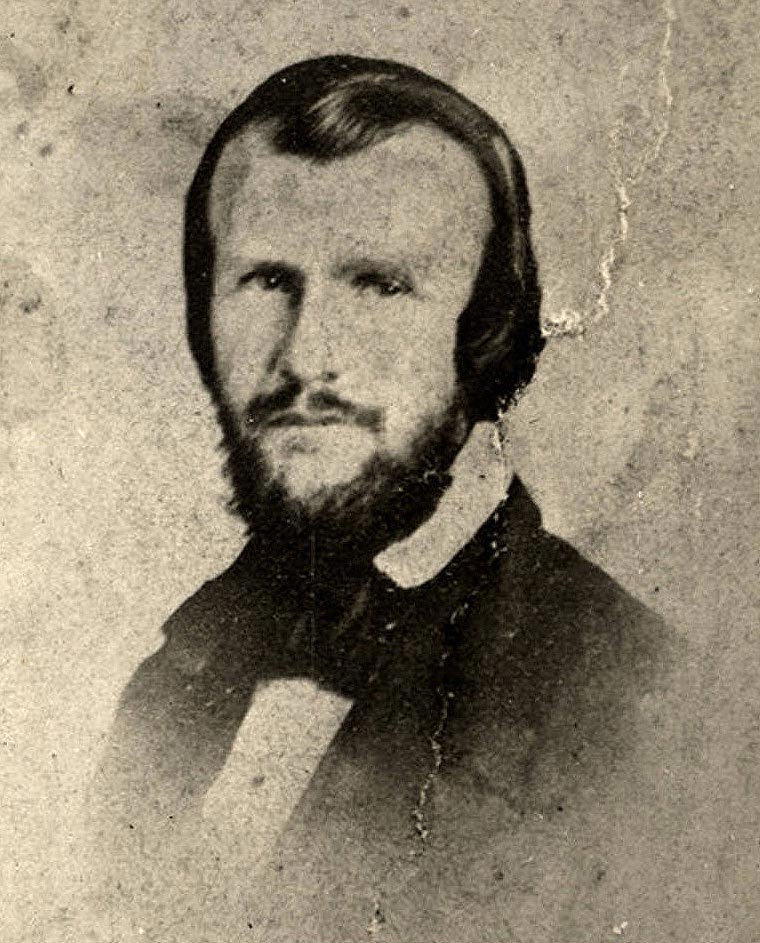

Dabney Herndon Maury (1822-1900)

A set of illustrations of the interior layout and operation of the Hunley

The crew conducted public trials in Mobile Bay in late July, 1863, proving the iron cigar-shaped “infernal machine” could move at four knots, dive, blow up a target anchored in the bay with a towed torpedo, resurface, and sail home. Confederate Admiral Franklin Buchanan (a conservative skeptic of the project), General Maury, and various other officers and observers were duly impressed with what now was considered an engineering marvel, unlike its predecessors, both Union and Confederate, none of which could be brought to completion or ever became a useful offensive weapon. Flag officer Buchanan wrote the squadron commander, John Randolph Tucker in Charleston, SC and the army commander there, Major General P.G.T. Beauregard, about the successful submarine trials, and subsequently received orders to ship it by rail to that city.

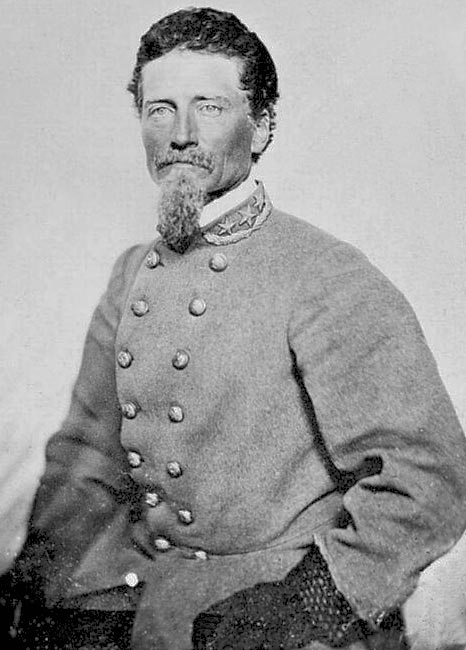

Franklin Buchanan (1800-1874)

John Randolph Tucker (1812-1883)

Charleston—the largest city still under Southern control, with 41,000 inhabitants—was under siege by a Union blockade mounting 231 pieces of artillery, many of the guns of heavy caliber, on both land and sea. To damage or break the blockade would breathe life and hope into a deteriorating military situation. The sea trials in Charleston Harbor took place at night, since a daytime attack would be spotted too soon. The original design engineer James McClintock captained the Hunley in its initial forays into the harbor. The Hunley failed to engage the enemy fleet after weeks of sailing, and returned empty-handed. General Beauregard gave orders for the army to seize the Hunley and man it with a Confederate naval crew; the operation of the free-enterprise submarine ended and the government took over.

Pierre Gustave Toutant-Beauregard

(1818-1893)

On August 29, an accident at the dock caused the Hunley to plunge to the bottom of the bay, drowning five of the new volunteer navy crewmen, with three escaping through the two hatches. Horace Hunley persuaded Beauregard to allow him to bring a new crew from Mobile to Charleston; men who had helped build the submarine and were very familiar with its operation. Led by twenty-year-old army veteran George Dixon as the new captain, five men from Mobile joined him to crew the vessel. On October 15, with Dixon absent but with Hunley himself at the helm, the ship sank in forty-two feet of water during a practice maneuver, killing all eight men aboard.

Historian Bill Potter addresses a tour group at the full-scale replica of the Hunley displayed outside The Charleston Museum

Lieutenant Dixon begged General Beauregard to give the boat one more chance to attack the Union blockading vessels. Skeptical but determined to use any means at his disposal, the General reluctantly approved another attempt. After cleaning and refitting the boat with a spar torpedo instead of a towed one, and with volunteers from the CSS Indian Chief added to Dixon’s crew, training began in November and December to prepare them for battle.

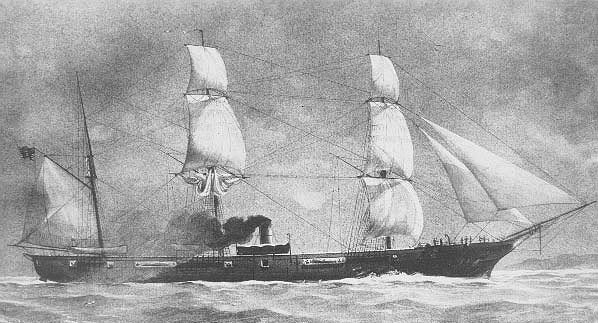

The USS Housatonic, sunk by the CSS Hunley on February 17, 1864 in Charleston Harbor—history’ first successful sinking of an enemy ship in combat by a submarine

At 8:45pm on February 17, 1864, the USS Housatonic—a 207 foot long, 1,240 ton sloop of war of the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron, bristling with seven heavy cannon—was on station outside Charleston Harbor. She had captured two blockade runners and helped reduce the city of Charleston to a pile of rubble, over its year and a half tour of duty in Charleston Harbor. Confederate traitors had made their way to the Union fleet commanders with the information about the H L Hunley, and the possible threat of a “torpedo boat that could swim underwater” tended to keep the watchmen diligent in their duties in the night. The night watch spotted the Hunley a hundred yards out and sounded the alarm. Small arms fire failed to stop the iron fish as it rammed the torpedo near the powder magazine and blew a huge whole in the side. The Housatonic sank quickly, but 155 of the 160-man crew escaped death. A submarine had sunk the first surface vessel in combat in history. There would be many more to come in history.

The Hunley, suspended from a crane during recovery from Charleston Harbor in 2000

The Hunley disappeared beneath the ocean waves, not to be rediscovered until 1970 or 1995, depending on who you believe. It was raised from its watery grave in 2000, and the crew buried in Magnolia Cemetery in 2004. Landmark Events visits the Hunley Museum in North Charleston for a private tour and lecture on the submarine. We also visit the gravesites of the valiant crews whose history-making exploits have captured the imaginations of multiple thousands of people ever since.

The graves of the last crew of the Hunley, Magnolia Cemetery, Charleston, SC—one of the stops on Landmark Events’ Charleston & Savannah Tour, April 19-23

Join us in April on our Charleston & Savannah Tour for a private tour of the research facility working to unlock the mysteries of the Hunley since its recovery. We’ll also visit the graves of her final crew at Magnolia Cemetery. Enjoy these unique experiences & much more! Learn More >

- For the full story of the CSS Hunley, I recommend The H. L. Hunley, The Secret Hope of the Confederacy by Tom Chaffin.

- For the amazing story of the discovery and restoration of the submarine since the year 2000, read The Hunley: Submarines, Sacrifice, & Success in the Civil War, by Mark K. Ragan (contains multiple pictures and documents), as well as Raising the Hunley: The Remarkable History and Recovery of the Lost Confederate Submarine, by Brian Hicks and Schuyler Kropf.

Image Credits: 1 Illustration of the Hunley (Wikipedia.org) 2 Horace Hunley (Wikipedia.org) 3 Charleston Harbor (Wikipedia.org) 4 Pioneer (Wikipedia.org) 5 Interior Sketches (Wikipedia.org) 6 Dabney Maury (Wikipedia.org) 7 Franklin Buchanan (Wikipedia.org) 8 John Randolph Tucker (Wikipedia.org) 9 P.G.T. Beauregard (Wikipedia.org) 10 USS Housatonic (Wikipedia.org) 11 Hunley Recovery (Wikipedia.org) 12 Graves (Wikipedia.org)