“And the fourth angel poured out his vial upon the sun; and power was given unto him to scorch men with fire. And men were scorched with great heat, and blasphemed the name of God, which hath power over these plagues: and they repented not to give him glory.” —Revelation 16:8-9

The Great Chicago Fire

October 8-10, 1871

![]() ire has destroyed many cities in the past. The great fire of London, England in 1661 consumed more than 13,000 homes and 87 parish churches as temperatures reached 2,280 degrees fahrenheit. Many saw it as divine judgement on a dissolute monarch, Charles II. In the American Civil War, the cities of Atlanta, Columbia and Richmond were burned after falling to Union forces. Many saw those burnings as judgement by a dissolute general. In World War II, Allied fire-bombings immolated 1,600 acres of the city center of Dresden, Germany, burning to death more than 25,000 people. The bombing raids on Tokyo, created firestorms that burned up sixteen square miles of the city and killed an estimated 100,000 civilians. In 1871, Mrs. O’Leary’s cow kicked over a lantern and burned down the city of Chicago.

ire has destroyed many cities in the past. The great fire of London, England in 1661 consumed more than 13,000 homes and 87 parish churches as temperatures reached 2,280 degrees fahrenheit. Many saw it as divine judgement on a dissolute monarch, Charles II. In the American Civil War, the cities of Atlanta, Columbia and Richmond were burned after falling to Union forces. Many saw those burnings as judgement by a dissolute general. In World War II, Allied fire-bombings immolated 1,600 acres of the city center of Dresden, Germany, burning to death more than 25,000 people. The bombing raids on Tokyo, created firestorms that burned up sixteen square miles of the city and killed an estimated 100,000 civilians. In 1871, Mrs. O’Leary’s cow kicked over a lantern and burned down the city of Chicago.

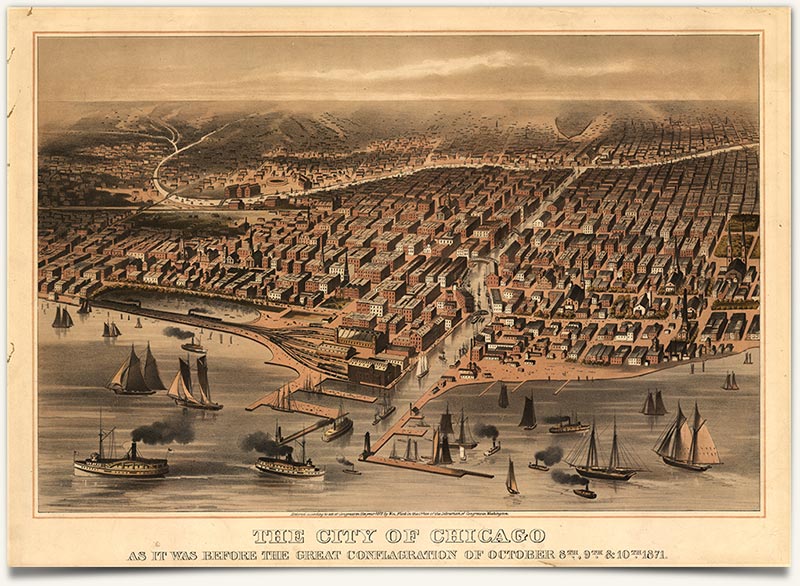

1871 Chicago view before the ‘Great Conflagration’

By 1871, the Windy City had become a major metropolitan Midwestern city, sporting a population of 340,000, along the shores of Lake Michigan. The city had not grown because of the business generated by the 26,000 Confederate prisoners of war that had starved, frozen, and died of disease six years earlier at Camp Douglas, the largest and most deadly Union prisoner of war camp in the Civil War, but from the success of railroads linking the city with the grain and livestock markets of the Midwest, till it became the most important rail hub in the United States. By 1870, more ships docked at this inland port than New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, San Francisco, Charleston, and Mobile combined. The city had grown so quickly that most of the buildings were constructed from wood, plentiful and cheap. The 561 miles of raised wooden sidewalks created horizontal pine chimneys which would draw thousands of cubic feet of oxygen and encircle the city in a stranglehold of fire if set ablaze. And set ablaze they were.

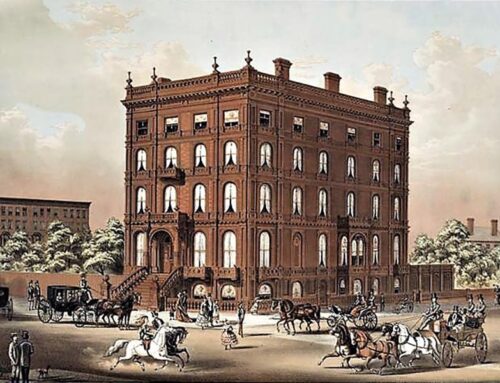

Mrs. O’Leary and her cow — the supposed cause of the fire

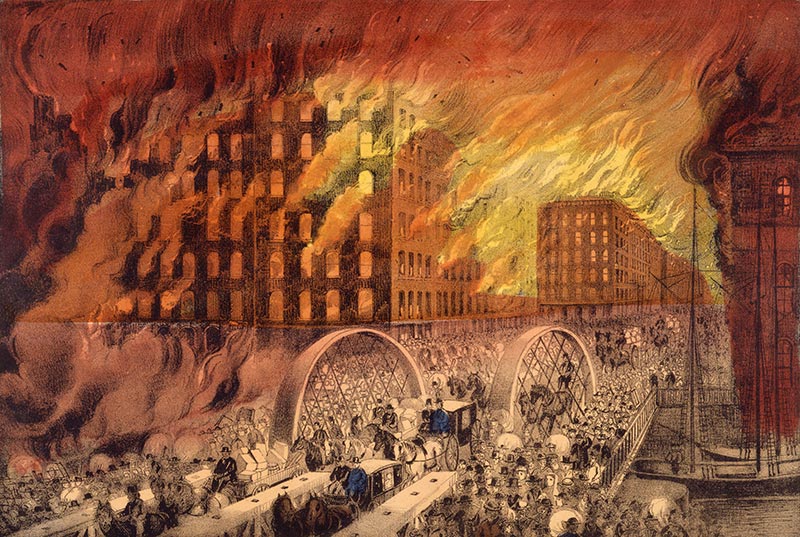

October 8, 1871, a fire broke out in the barn of the O’Leary family on the city’s west side. The understrength and dispersed fire companies of the city were quickly overwhelmed as the fire leaped from building to building and street to street; many roofs were tarred. Convection whirls sucked the fire one hundred feet in the air, giving an appearance of tornadoes of heat and ash. A lumber mill, furniture factory and box factory stood side by side and provided acceleration fuel to the uncontrollable blaze. In one hour, the fire crossed the Chicago River to the South Side when burning debris ignited a horse stable — the Parmelee Omnibus and Stage Company. A roofing material company and the gas works quickly caught fire. On the north side of the city, a train of railroad cars containing oil caught fire, touching off the Wright Brothers’ Stables.

This Currier & Ives lithograph depicts people fleeing across the Randolph Street Bridge. Thousands of people literally ran for their lives to escape the flames. One survivor wrote: “The whole earth, or all we saw of it, was a lurid yellowish red. Everywhere dust, smoke, flames, heat, thunder of falling walls, crackle of fire, hissing of water, panting of engines, shouts, braying of trumpets, roar of wind, confusion, and uproar.”

People fled to the beaches of Lake Michigan, some trying to remain underwater, others wading out as far as they dared. It took two days for the fire to burn itself out with the untiring help of the exhausted firemen. It had destroyed 3.3 square miles of the city, obliterated about 17,500 buildings and killed an estimated three hundred people, perhaps many more, since the conflagration was so hot that bodies were completely incinerated. The post-fire investigators set out to determine what caused the fire.

1871 panoramic of Chicago after the fire

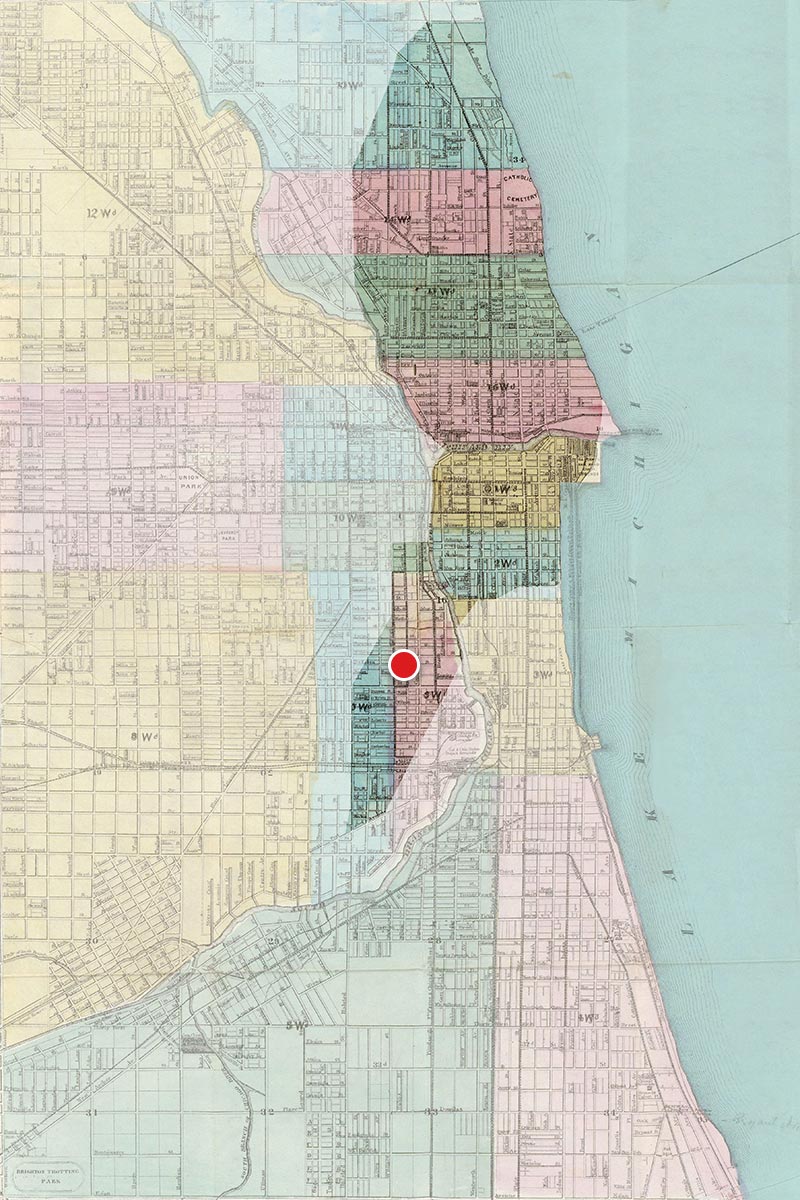

Early in the rumor mills of the city, a story made the rounds that Mrs. O’Leary’s cow kicked over the lantern, and that tale is still believed to this day by many people. After interviews with fifty witnesses, it could not be concluded that the cow did the deed. Alternative theories have abounded; Richard Bales in The Great Chicago Fire and the Myth of Mrs. O’Leary’s Cow claims to have definitively solved the greatest mystery of Chicago’s history. Whatever the truth, Mrs. O’Leary, Al Capone, and Michael Jordan still hold the lead positions of recognition for the City of Chicago. The O’Leary property today is, appropriately, a fire academy. Once the providential and uncontrollable holocaust was spent, the city rebuilt, with all sorts of lessons learned about building materials, fire departments, codes, and strategic planning, to become the third largest city in America.

Map of Chicago, highlighting the burned area and indicating the starting point of Mrs. O’Leary’s barn (red dot)