“If it be possible, as much as lieth in you, live peaceably with all men.” —Romans 12:18

Uncle Tom’s Cabin, June 5, 1851

![]() ertain books have changed the course of American history. Thomas Paine’s Common Sense in 1776 inflamed the passions of patriots considering independence from Britain, and tipped others who had been undecided, into the patriot cause. Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of the Species transformed the scientific community and then the general population to accept evolution as the theory that best explained the origins of man and animals. The novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe molded the opinions of a million people in the Northern states regarding the nature and course of the slave system of the American South. The book created stereotypes and inflamed hatreds that played a key role in the greatest cataclysm of American history — the Civil War.

ertain books have changed the course of American history. Thomas Paine’s Common Sense in 1776 inflamed the passions of patriots considering independence from Britain, and tipped others who had been undecided, into the patriot cause. Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of the Species transformed the scientific community and then the general population to accept evolution as the theory that best explained the origins of man and animals. The novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe molded the opinions of a million people in the Northern states regarding the nature and course of the slave system of the American South. The book created stereotypes and inflamed hatreds that played a key role in the greatest cataclysm of American history — the Civil War.

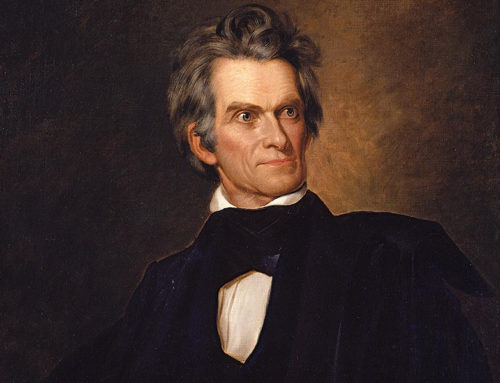

Harriet Beecher Stowe (1811-1896),

American abolitionist and author who is best known for her novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin

Harriet Beecher was the seventh of thirteen children of the famous evangelist Lyman Beecher, and sister to the radical abolitionist, women’s suffragist, Darwinist, and scandal-ridden preacher Henry Ward Beecher. At the age of twenty-one, Harriet moved from Connecticut, where she had been born, to Cincinnati, Ohio to join her father, who had become president of Lane Seminary. She married Massachusetts-born seminary professor Calvin Stowe, a brilliant scholar of Semitic languages and promoter of public schools on the Prussian model. Together they would produce seven children and books on a variety of subjects.

As ardent abolitionists, the Stowes used their home as a stop on the “underground railroad”, the secret path to freedom in Canada for slaves fleeing Kentucky. Although young Harriet never visited a Southern state, she spoke with runaway slaves and black victims of race riots in Cincinnati fomented by Irish immigrants, and later by northern-born whites. The nation veered perilously close to secession in 1850 when Congress debated whether to allow slavery in the new territories gained from the war with Mexico. The Compromise of that year by the Congress temporarily mollified men closest to “the center” of both major parties. One of the provisions of “The Compromise of 1850” included a more vigorous national Fugitive Slave Law, which infuriated the abolitionists who insisted on immediate emancipation of slaves.

Harriet Beecher Stowe House in Cincinnati, Ohio, among the homes included on the list of Underground Railroad sites

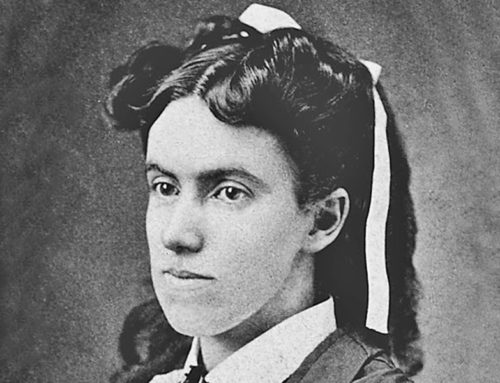

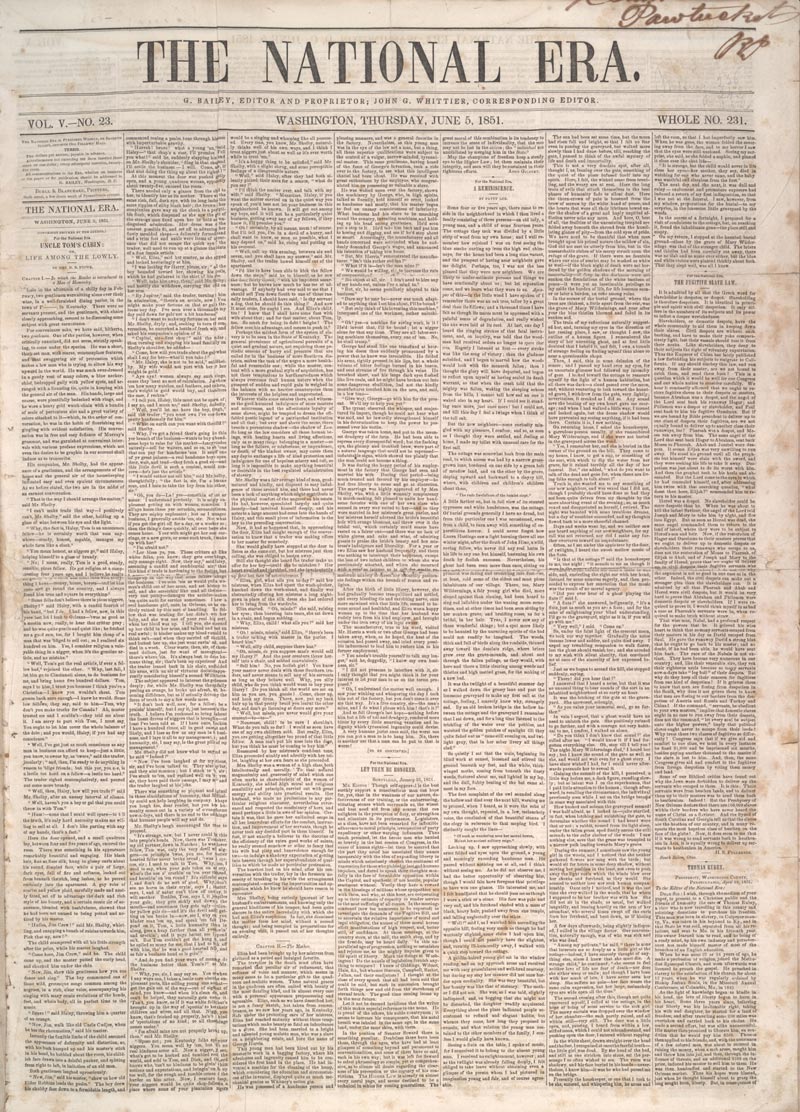

Uncle Tom’s Cabin first appeared as a 40-week serial in The National Era, an abolitionist periodical, starting with this June 5, 1851 publication

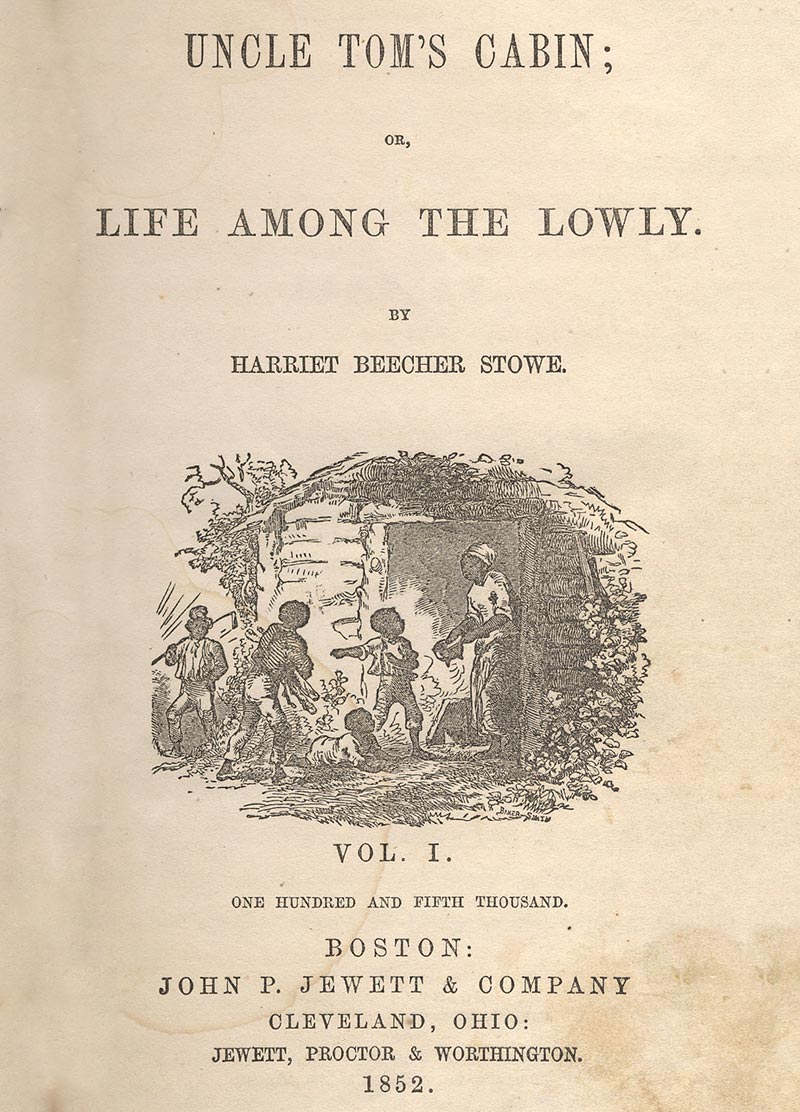

Title page for Volume I of the first

Harriet claimed to have had a special vision of a dying slave, inspiring her to put pen to paper and begin what would become the book Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Calvin Stowe by then was a professor at Bowdoin College in Maine, and from there his wife began the newspaper serial that would become the book. In 1852, the forty-year-old authoress was convinced to publish the story in book form. Although she was skeptical at first, they published an initial print run of five thousand, and before the year was out, more than three hundred thousand had been sold. It became the best-selling book (behind the Bible) in the 19th Century; there were more than 1.5 million copies sold in Great Britain alone, and it had been translated into several other languages.

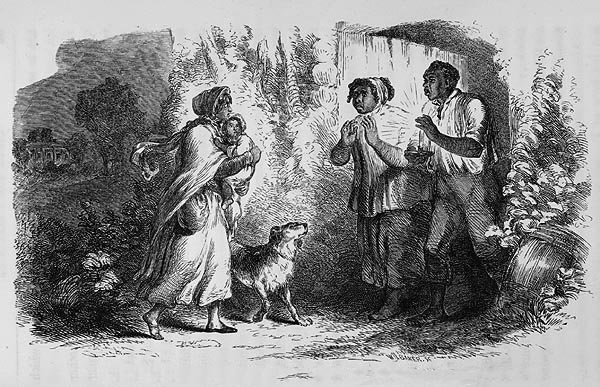

Illustration by Hammatt Billings for the first edition of Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852). Eliza tells Uncle Tom that he has been sold and she is running away to save her child.

The story itself was inspired by a variety of sources, from published slave narratives, to interviews with runaways, and Mrs. Stowe’s active imagination, reconstructing what the abolitionist literature assured America were the cruelties and depravity of all slavery in the Southern states. Some of the inspiring materials she claimed were actually published after her book came out.

The power of the novel was in the telling, with pathos, love, Christian fortitude, cruelty, suspense, hatred and humanity. The characters became iconic American figures — Uncle Tom, little Eva, Simon Lagree the overseer, etc. The story brought tears of compassion and outrage to the readers of the North. In the South, the book was banned as subversive of social order. Reviewers there also considered it exaggerated, tendentious and overly emotional, striking at the root of the paternalistic moral and familial order that they believed was more characteristic of plantation life below the Mason-Dixon Line.

Harriet Beecher Stowe, c. 1870s-1880s

In the 1870s and 1880s, Stowe and her family wintered at their home in Mandarin, Florida, now a neighborhood of modern consolidated Jacksonville

Of all the events of the decade previous to secession and war, this book stands out as an unique contribution to the widening of the breach between the sections, and, claiming to be an expression of Christian concern, between the churches who had already parted ways over the divisive issue of slavery.