“The king’s heart is a stream of water in the hand of the Lord; he turns it wherever he will.” —Proverbs 21:1

Charles I of Spain Becomes

Holy Roman Emperor, 1519

![]() he King of Spain, Charles I (1500-1558), became Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor, at the age of nineteen. Turning over to a teenager the most important and powerful position in Christendom, outside the papacy, could have been better timed, perhaps. His accession to the throne of the Holy Roman Empire in 1519 providentially associated with the controversies and debates with the towering intellect of the heroic and stubborn protesting monk of Saxony, Martin Luther, and all the other men of the Protestant Reformation. Charles would spend the next thirty-five years attempting to re-assert the Habsburg family’s authority over the German princes, and maintaining a united western Church. What could go wrong?

he King of Spain, Charles I (1500-1558), became Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor, at the age of nineteen. Turning over to a teenager the most important and powerful position in Christendom, outside the papacy, could have been better timed, perhaps. His accession to the throne of the Holy Roman Empire in 1519 providentially associated with the controversies and debates with the towering intellect of the heroic and stubborn protesting monk of Saxony, Martin Luther, and all the other men of the Protestant Reformation. Charles would spend the next thirty-five years attempting to re-assert the Habsburg family’s authority over the German princes, and maintaining a united western Church. What could go wrong?

Pope Clement VII and Emperor Charles V during the entry of the Pope and the Emperor into Bologna in 1530, when the latter was crowned as Holy Roman Emperor by the former

Charles V’s maternal grandparents had received a dispensation from the Pope to marry, since they were second cousins, a consanguinity prohibited by the Catholic Church. The match of the 17-year-olds Ferdinand and Isabella, however, united the kingdoms of Castile and Aragon, the Spanish monarchs who sponsored the Christopher Columbus voyages. Their marriage produced Charles’s mother, known as Joanna the Mad. Charles’s father was a Habsburg Prince known as Phillip the Handsome, oldest son of the Holy Roman Emperor, making Charles in a few short years, presumptive heir of Austria, as well as of Burgundy and the Low Countries, and most important of all, Spain. A sword and helmet were the appropriate royal gifts to the infant Charles, who should, perhaps, have grown up to be crazy good-looking and the all-powerful monarch of Europe. As providence would have it, he inherited the Habsburg jaw, a distinctive deformity, and stubborn German Protestants, willing to die for their faith.

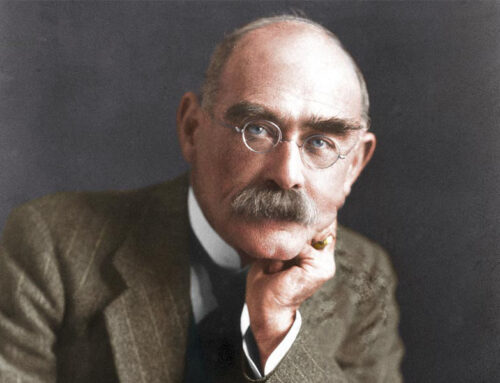

Philip I of Castile (1478-1506), father of Charles V

Joanna I of Castile and Aragon (1479-1555), mother of Charles V

Born in Flanders, Charles inherited the Netherlands at the age of six. In 1519, as Charles V, he was appointed as The Holy Roman Emperor, King of the Germans in modern parlance, but crowned by the Pope ten years later. The highly educated monarch spoke his native Dutch and French, as well as Latin, Castilian Spanish, Basque and German. The Emperor spent much of his time travelling among his dominions, which he ruled over through regents, including his brother Ferdinand. His early years of energetic leadership proved promising—he gave the Knights of St. John the Island of Malta to defend Christendom’s southern flank in the Mediterranean, a strategy that eventually produced military successes in North Africa and a great victory over the Ottomans in 1565. Although he distrusted the Pope, Charles determined to defend the Roman Catholic faith against the rising tide of Protestant rebellion.

Charles I of Spain and V of the Holy Roman Empire (1500-1558)

When Martin Luther’s writings were brought to the Emperor’s attention, he called for the Diet of Worms to try the “heretic.” Concluding that Luther was definitely outside accepted Roman Catholic doctrine, he declared him an outlaw, but honored the safe-conduct pass from Worms. Charles declared in the edict:

“You know that I am a descendant of the Most Christian Emperors of the great German people, of the Catholic Kings of Spain, of the Archdukes of Austria, and of the Dukes of Burgundy. All of these, their whole life long, were faithful sons of the Roman Church… After their deaths they left, by natural law and heritage, these holy catholic rites, for us to live and die by, following their example. And so until now I have lived as a true follower of these our ancestors. I am therefore resolved to maintain everything which these my forebears have established to the present.”

Reformer Martin Luther testifying at the Diet of Worms, 1521

Charles was, however, only as powerful as his army and his alliances permitted, so his dependence on the German princes, including the Lutherans, constrained his actions against the reformers. Luther’s Prince of Saxony protected him and Charles sought ways to reach rapprochement, postponing the doctrinal controversies, as long as the Lutheran league of Princes (Schmalkaldic League) continued support of war against the Muslims and the French. For Catholic France, imperial designs also trumped religious contention. Hoping the Pope would settle the reformation problems for the Holy Roman Emperor only postponed war for a few years, thus allowing Protestantism to expand across Europe. From 1547 till his retirement in 1556, Charles V fought his own Protestant princes, France, the Ottoman Turks, and combinations of those enemies, exhausting himself and his empire, and causing untold misery to the German people in general.

An allegorical depiction of Charles V enthroned, surrounded by those whom he had conquered: (L-R) Suleiman I of the Ottoman Empire, Pope Clemens VII, Francis I of France, the Duke of Cleves, the Duke of Saxony and Philip I, Landgrave of Hesse

Between 1554 and 1556, Charles, suffering greatly from gout and epilepsy, gave up several of his lands and titles, and divided others, thus dismembering the Habsburg Empire. In his final abdication speech before entering a monastery, he recounted his attempt to hold the largest geographical boundaries in the history of Christendom by recounting his travels: ten to the Low Countries, nine to Germany, seven to Spain, seven to Italy, four to France, two to England, and two to North Africa. His last public words as he stood, depressed and exhausted, leaning on another, were, “my life has been one long journey.” His territory stretched from Mexico to Munich and from Sicily to the Zuider Zee.

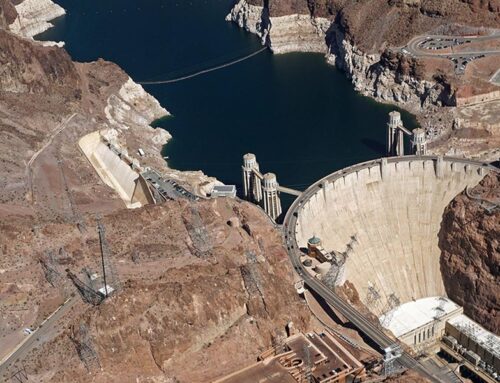

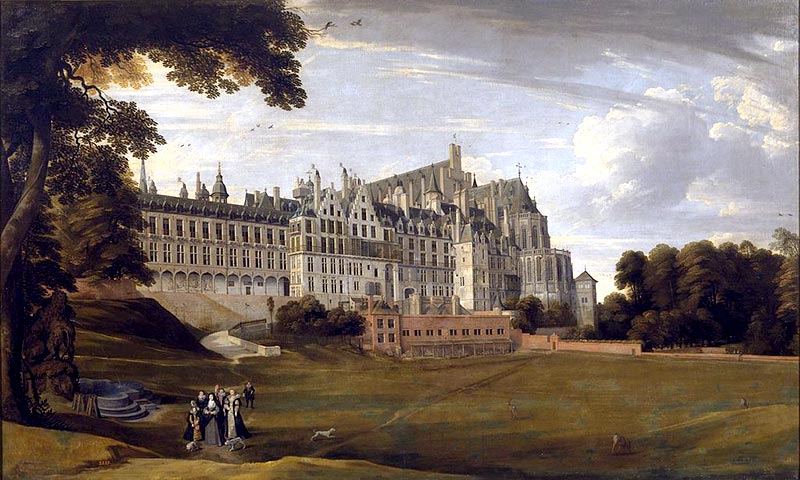

The Palace of Coudenberg, Brussels, Belgium, from where Charles issued his various abdications

At 26, Charles had married Isabella of Portugal—a match that began as a political move, but which quickly became a deep and abiding love match. After she died thirteen years later, the Emperor dressed in black the rest of his life, in mourning, and never remarried. Their son Phillip was destined to become King Phillip II of Spain, a man of historical importance in his own right. He would carry on the war against the Reformation churches that his father failed to quell in his day, make a gallant attempt at conquering England with the Great Armada, and, in God’s Good Providence, fail.

Holy Roman Emperor Charles V and his wife, Empress Isabella of Portugal