“Whatsoever you do, do all to the Glory of God.”

—1 Corinthians 10:31b

Cyrus McCormick Patents Reaper, June 21, 1834

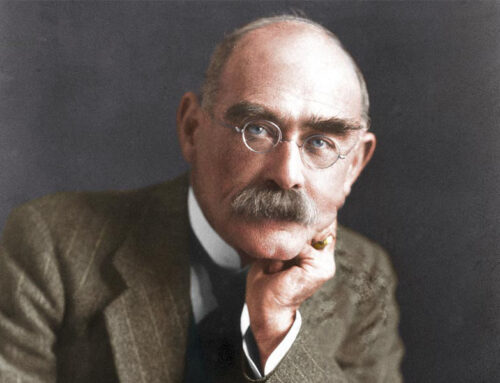

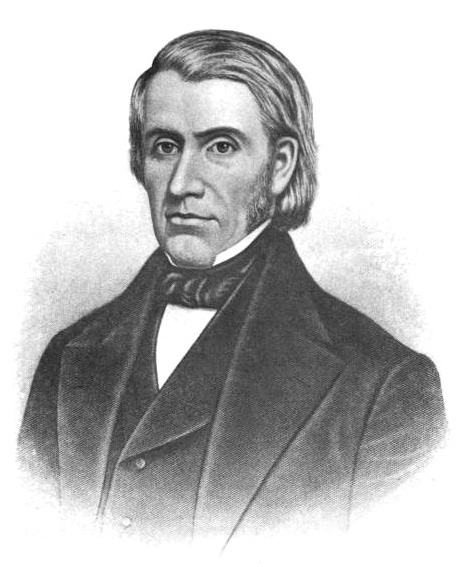

![]() echnological advances sometimes effect changes that improve the lives of millions. The invention of moveable type, mass-produced interchangeable parts, the cotton gin, the mechanical reaper, jet propulsion, wireless telegraph and telephones, internal combustion engines, and many other achievements have transformed the world. Most of those inventions were the end-product of the work of many people trying to solve a problem, meet particular needs, or just reduce manual labor. Not surprisingly, Christians have been in the forefront of breakthrough designs and practical applications of creation principles. One of those men received a patent on June 21, 1843, revolutionizing farming and transforming food production for the world. That man was Cyrus McCormick (1809-1884).

echnological advances sometimes effect changes that improve the lives of millions. The invention of moveable type, mass-produced interchangeable parts, the cotton gin, the mechanical reaper, jet propulsion, wireless telegraph and telephones, internal combustion engines, and many other achievements have transformed the world. Most of those inventions were the end-product of the work of many people trying to solve a problem, meet particular needs, or just reduce manual labor. Not surprisingly, Christians have been in the forefront of breakthrough designs and practical applications of creation principles. One of those men received a patent on June 21, 1843, revolutionizing farming and transforming food production for the world. That man was Cyrus McCormick (1809-1884).

Cyrus Hall McCormick (1809-1884)

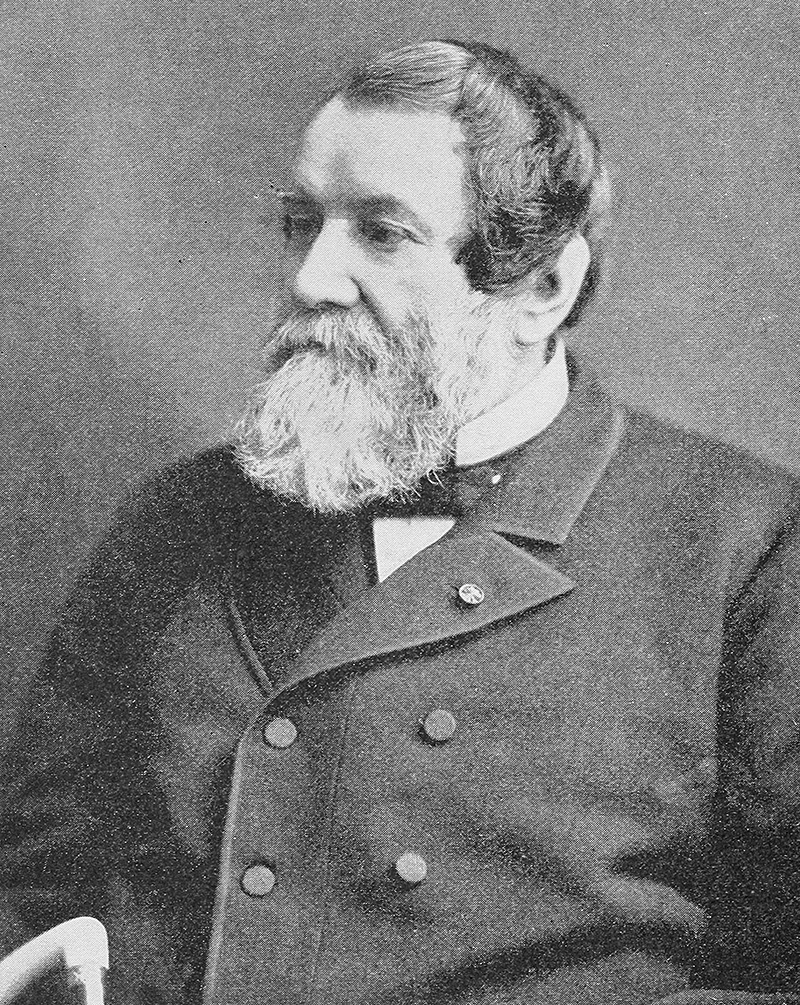

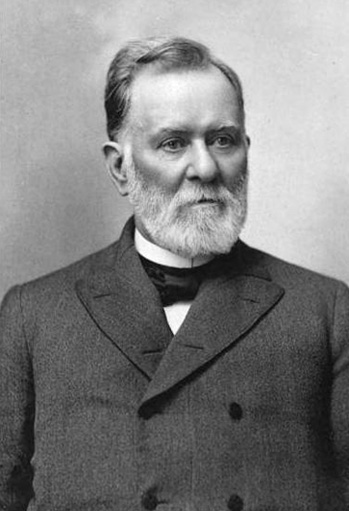

His great-grandfather came to America from Ulster, part of the great Irish Presbyterian diaspora which populated the frontiers of Pennsylvania. His grandfather brought the McCormicks south to settle in Rockbridge County, Virginia, and fought in the War for Independence at the Battle of Guilford Courthouse. Cyrus’s father expanded the family’s fortunes through land acquisition (1,800 acres), entrepreneurial business and building (two gristmills, two sawmills, a distillery, and a blacksmith shop). Born in 1809, Cyrus inherited his father’s talents and began experimenting in mechanics at an early age. His father, Robert, actually invented and patented several machines—a thresher and a hydraulic “hemp-breaker”—but his twenty-eight-year effort to build a grain harvester proved unsuccessful.

Robert Hall McCormick (1780-1846), inventor, and father of Cyrus McCormick

The McCormick family farm, Walnut Grove, in Steele’s Tavern, VA. The farm was built by Cyrus’s father, Robert, and it was in this blacksmith shop on the left where Cyrus built his first harvesters. The family grist mill is on the right.

Those experiments did not go to waste, however, for Cyrus—with the assistance of Jo Anderson, one of the McCormick servants—designed and fabricated a reaper pulled by horses. Building upon his father’s idea, Cyrus described his creative adaptation thus:

“I conceived the idea of cutting. . . with a vibrating blade operated by a crank and the grain supported at the edge while cutting by means of fixed pieces of iron projections before it. . . A very successful experiment was made with it in a field cutting oats. . . the machine was balanced upon two wheels, [with] the horses in front and to one side. . . causing the machine to accommodate itself to the irregularities of the ground.”*

The year was 1841, and the patent took three years to reach fruition on June 21, 1834. His father told a neighbor, “I am proud that I have a son who could accomplish what I failed to do.” Would that every father could have the occasion to say those words.

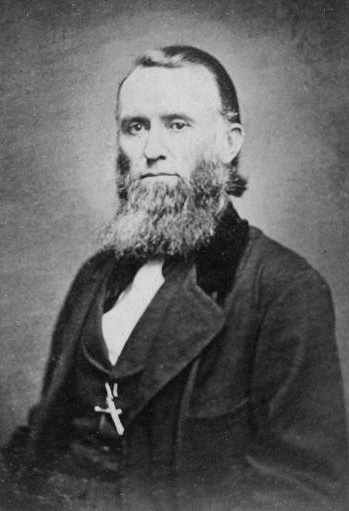

Leander James McCormick (1819-1900), Cyrus’s younger brother and business partner

William Sanderson McCormick (1815-1865), Cyrus’s younger brother and business partner

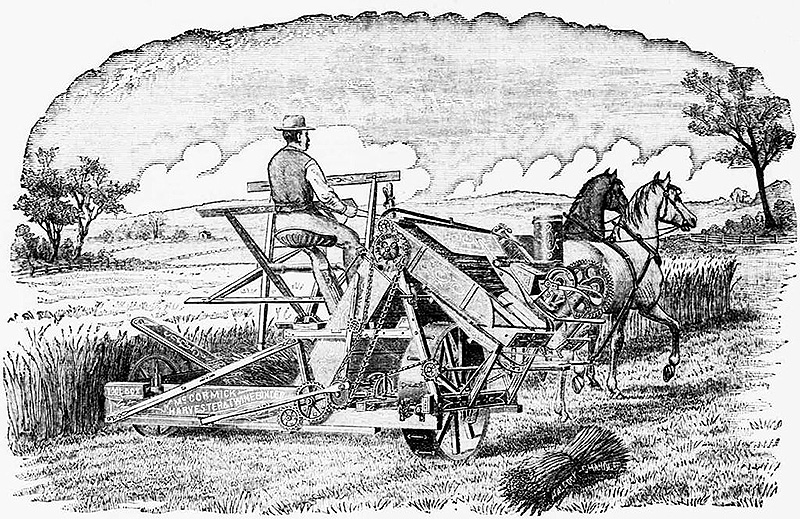

Every future competitor copied the salient features of the prototype McCormick Reaper, setting off a lifetime of lawsuits, controversies with the patent office, and fixing the occasional mechanical difficulties. Providentially, twenty-two-year-old Cyrus McCormick proved to be a man of “inventive genius, undaunted courage, untiring energy and of unswerving courage.” He scheduled field trials in farms around Lexington, the county seat. The reaper needed tweaking but eventually received newspaper coverage and endorsement by prominent Virginia supporters. The demand for reapers, however, took five years to stimulate after the patent had been secured. Improved castings, further field trials and exhibitions in rural counties around Rockbridge enabled Cyrus to begin manufacturing and selling his machine. From 1842 to 1850 he built 778 machines, only a very few shipping by wagon to the grain states of the midwest, “where land was flat and labor scarce.”

An 1884 version of the McCormick Reaper which also bound the harvest

Cyrus formed a partnership with the mayor of Chicago who invested $25,000 in the company, enabling the company to move the manufacturing to that city. Cyrus convinced two of his brothers to move there and assist him. Competitors “lawyered up” and formed a cabal of resistance before the patent office to block McCormick’s patent renewal in 1852. They succeeded, but the ending of his patent only spurred the energetic McCormick to greater efforts of marketing and manufacturing his machines. Cyrus swept the competition from the field (so to speak), through superior quality parts and machines, enabling buying on credit, and a policy to never sue a farmer for his failure to pay. He took his machine to Europe, where it created a sensation, and its use increased grain productivity exponentially. As the American frontier expanded, the McCormick Reaper travelled with the pioneers, making the midwest the bread basket of the entire nation. Edwin Stanton, Lincoln’s Secretary of War, claimed that the Virginian’s invention “carried civilization westward more than fifty miles per year . . . and took the place of regiments of young men in the Western harvest fields, releasing them to do battle for the Union,” as well as feeding them at the battle-front.

The Crystal Palace at the Great Exhibition in London, 1851, where McCormick exhibited his McCormick Reaper with great success

McCormick retained a loyalty to his home state, pleading for reconciliation of the sections before and during the Civil War, a very unpopular position to hold in Chicago at that time. He spent much of the Civil War years in Europe, believing and perhaps hoping, that the Confederacy would succeed. He unsuccessfully ran for Congress on a “Peace Democrat” platform in 1864.

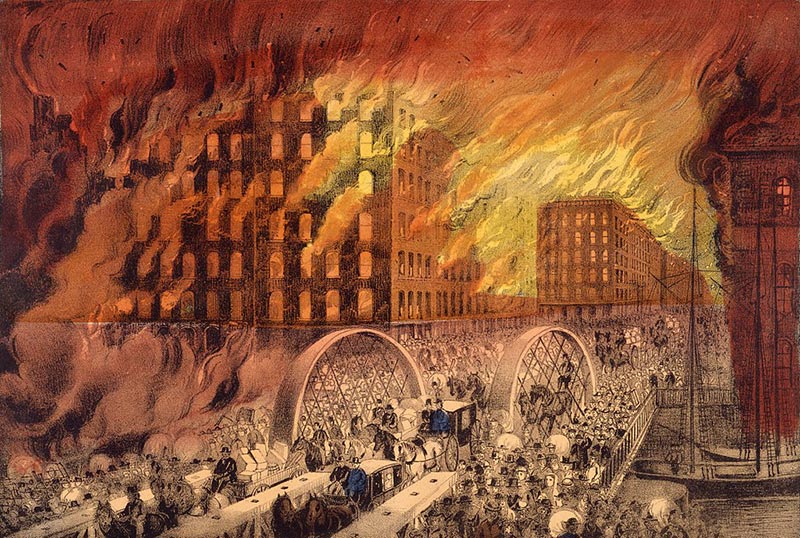

In 1871, the Great Chicago Fire burned the McCormick factory, however, at the urging of Cyrus’ wife, Nettie, it was rebuilt and back in production by 1873.

An outspoken Christian businessman and a lifelong Presbyterian, McCormick endowed four theological chairs at what became McCormick Theological Seminary in Chicago. He donated $10,000 to help Dwight L. Moody start the YMCA, and his own son Cyrus, Jr. became the first President of Moody Bible Institute. Cyrus and his wife Nettie Day donated large sums to Tusculum College, a Presbyterian school in Tennessee, and helped start churches and Sunday Schools all across the South after the War. In the last 20 years of his life, Cyrus served on the Board of Trustees of Washington and Lee College in his native Lexington, Virginia.

After Cyrus’s death, Nettie donated more than $160 million (in today’s money) to hospitals, disaster relief, churches and other private institutions. A beautiful statue of Cyrus stands near the President’s house on the campus of Washington and Lee College, and his farm near Steele’s Tavern, Virginia contains a free museum and is run as an experimental farm by Virginia Tech University. One historian summed up McCormick’s achievement: “in this remote community was invented the instrument which wrought the greatest change in agriculture that has ever taken place, and which has affected profoundly the economic life of the world.” As if that isn’t enough, Cyrus McCormick used his profits to affect the spiritual life of the world.

Nancy Maria “Nettie” Fowler McCormick (1835-1923), wife of Cyrus

*As quoted in The McCormick Reaper by Dr. John Latané, John’s Hopkins University

Image Credits: 1 Cyrus McCormick (Wikipedia.org) 2 Robert McCormick (Wikipedia.org) 3 McCormick Farm (Wikipedia.org) 4 Leander McCormick (Wikipedia.org) 5 William McCormick (Wikipedia.org) 6 Reaper (Wikipedia.org) 7 Crystal Palace (Wikipedia.org) 8 Great Chicago Fire (Wikipedia.org) 9 Nettie McCormick (WisconsinHistory.org)