“Whoever strikes a man so that he dies shall be put to death.”

—Exodus 20:2

Chief Metacom Killed,

August 12, 1676

![]() n recent mythologizing of the American past, some historians have succumbed to various strains of leftist propaganda and ideological rhetoric regarding the Pilgrims and their relationship with the native tribes they encountered in New England. Particularly odious has been the attempt to attribute to the settlers of 1620 motives of theft of property, hatred and genocide. Such ridiculous invention flies in the face of reality and careful research in the records of those days, and the years that followed. While there had been some contention and warfare between the Puritans and allied tribes against the Pequots, more than fifty years passed from the initial treaty between the Pilgrims and the Wampanoags before a major war occurred that spelled the end of peaceful relations with most native tribes. That war engulfed all of New England, killing more people in relation to the population than any other war in American history. The chief instigator was Chief Metacom, popularly known by the Englishmen as “King Philip.”

n recent mythologizing of the American past, some historians have succumbed to various strains of leftist propaganda and ideological rhetoric regarding the Pilgrims and their relationship with the native tribes they encountered in New England. Particularly odious has been the attempt to attribute to the settlers of 1620 motives of theft of property, hatred and genocide. Such ridiculous invention flies in the face of reality and careful research in the records of those days, and the years that followed. While there had been some contention and warfare between the Puritans and allied tribes against the Pequots, more than fifty years passed from the initial treaty between the Pilgrims and the Wampanoags before a major war occurred that spelled the end of peaceful relations with most native tribes. That war engulfed all of New England, killing more people in relation to the population than any other war in American history. The chief instigator was Chief Metacom, popularly known by the Englishmen as “King Philip.”

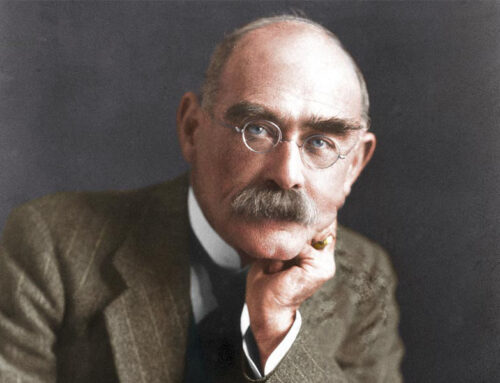

Chief Metacom, also known as King Philip (1638-1676), son of Massasoit and chief of the Wampanoag people after the deaths of his father and older brother

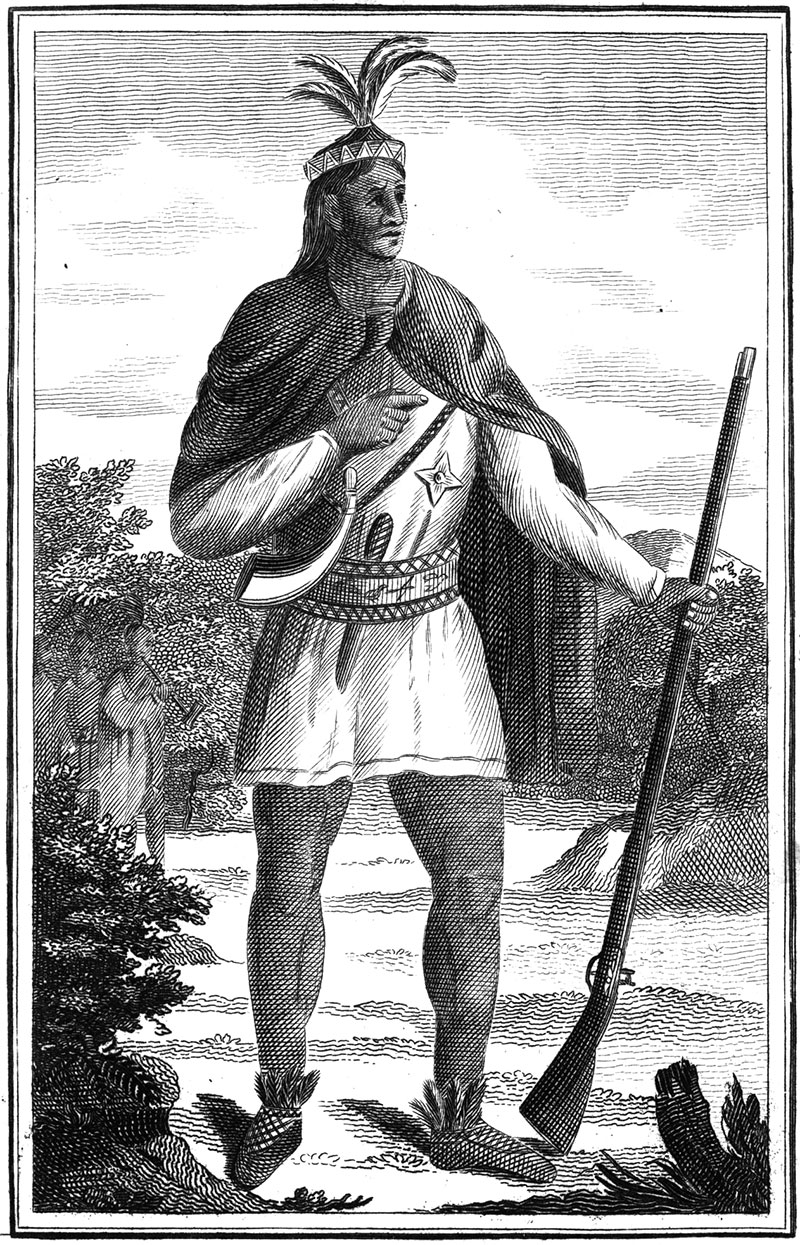

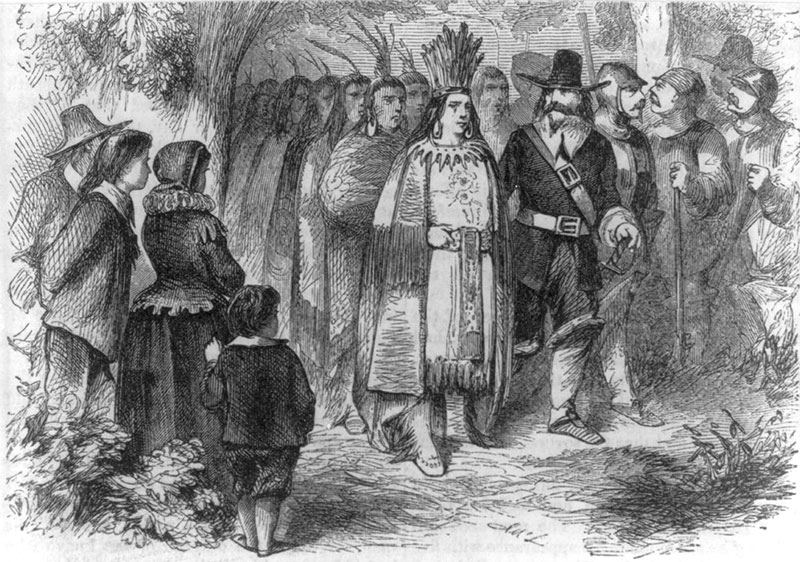

Chief Massasoit with some of his warriors and the Pilgrims, with whom his people enjoyed a long and peaceful relationship, until his son, King Philip, instigated war

Metacom (of Pokanoket) was the second son of the chief Sachem of the Wampanoag tribe, Massasoit, who brokered the treaty with the Plymouth colonists (Pilgrims) in 1621. Metacom and his brother both officially adopted English names, Alexander and Philip, after reaching adulthood, a not uncommon practice among the natives. Also during the fifty years of peace, numerous native tribesmen came to faith in Christ through the efforts of missionaries who learned the languages, taught the Bible, and established churches and “praying villages.” The Plymouth Colony expanded through land purchases from the natives.

The Old Indian Meeting House in Mashpee, MA was built in 1684 and used by early Wampanoag Christians

King Philip at a treaty table with settlers

| Celebrate the 400th Anniversary of Thanksgiving in Plymouth, Nov 15-20! Venues include the Mashpee Meeting House, Praying Indian Village sites, Plimoth Plantation, Cape Cod, Duxbury & much more! Learn More > |  |

Both cultures, for the most part, kept to the terms of the treaties, fulfilling the requirements of justice for criminal behavior by Englishmen or Wampanoag. Also during the treaty years, many more colonists arrived, increasing the number of Englishmen not members of the church, or loose and unattached on the frontier, or just looking for “the main chance” to prosper at the native’s expense, especially in land acquisition. Puritans, but not Separatists, founded the Massachusetts Bay Colony to the north of Plymouth, which exceeded the population and geography of Plymouth within a short period of time. By 1675, one hundred years before the War for American Independence, the English population of New England exceeded 65,000, in 110 towns, with added colonies of Connecticut and Rhode Island, while the major native tribes like the Massachusetts, Nipmucs, Narragansetts, and Wampanoags could probably count about 10,000. They all spoke Algonquian dialects.

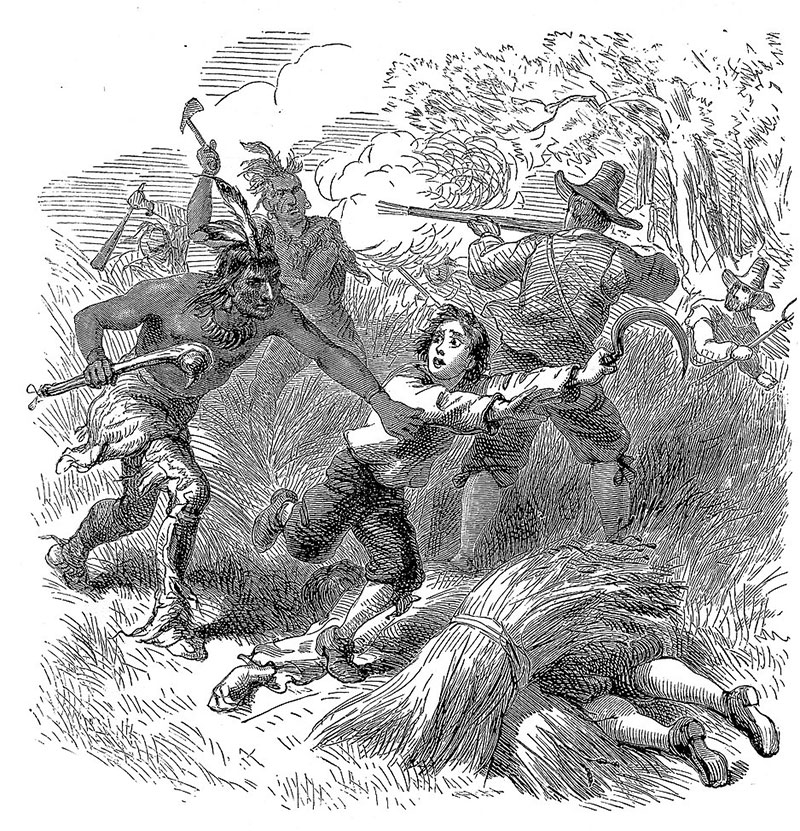

Indian assault on Ayres’ Inn as part of King Philip’s War, August 4, 1675

In 1662, Metacom, known as King Philip, acceded to the throne of the Wampanoag confederacy as chief Sachem. He distrusted the Englishmen and harbored animosity toward the “praying Indians” as having abandoned their own culture and accepted European ways. In January of 1675, an Indian Christian named Sassamon, who served as intermediary between the governor of Plymouth and the Wampanoag leaders, reported that Philip was plotting an attack on the colony. The English leaders warned the sachem that should such reports be true, the Wampanoags could face further loss of land and weapons. Someone murdered Sassamon and threw him in a pond. Three Wampanoags were accused, tried and hanged by the Plymouth court. Infuriated, King Philip’s warriors attacked and wiped out the militia of Swansea. A retaliatory raid was made on the Wampanoag settlement at Mount Hope, which was found abandoned, but was burned.

Assawompset Pond—King Philip’s War began with the discovery of John Sassamon’s body and the subsequent trial of his suspected murderers. His body was slipped under the ice on Assawompset Pond and found the following spring. The outcome of the trial sparked the beginning of hostilities.

An Indian attack on local settlers would spare no one: man, woman or child

The Nipmucs joined with the Wampanoags and the war on the Plymouth, Connecticut, and Massachusetts frontiers blazed with extreme violence against men, women and children. The settlements of Middleborough, Dartmouth, Brookfield, Lancaster, Deerfield, Hadley, Springfield (CT), and Northfield were attacked, with great loss of life. Although not officially at war with the Narragansetts, the tribe had aided and abetted King Philip’s forces. A thousand New England troops made a preemptive strike against their main fort in Rhode Island, killing about 600 Narragansetts. The Pequots and Mohegans were allied with the English and took part in what became known as “The Great Swamp Fight.”

The Battle of Bloody Brook took place when a band of men, transporting the harvest, were attacked by a body of Nipmuc, resulting in the loss of at least 57 settlers

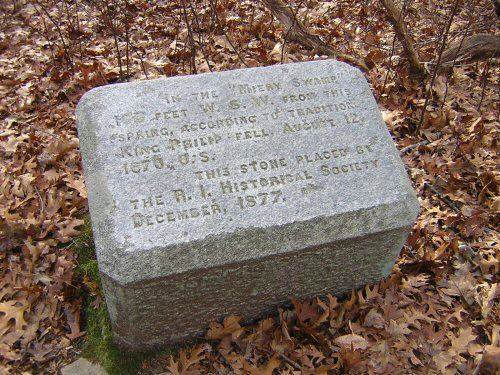

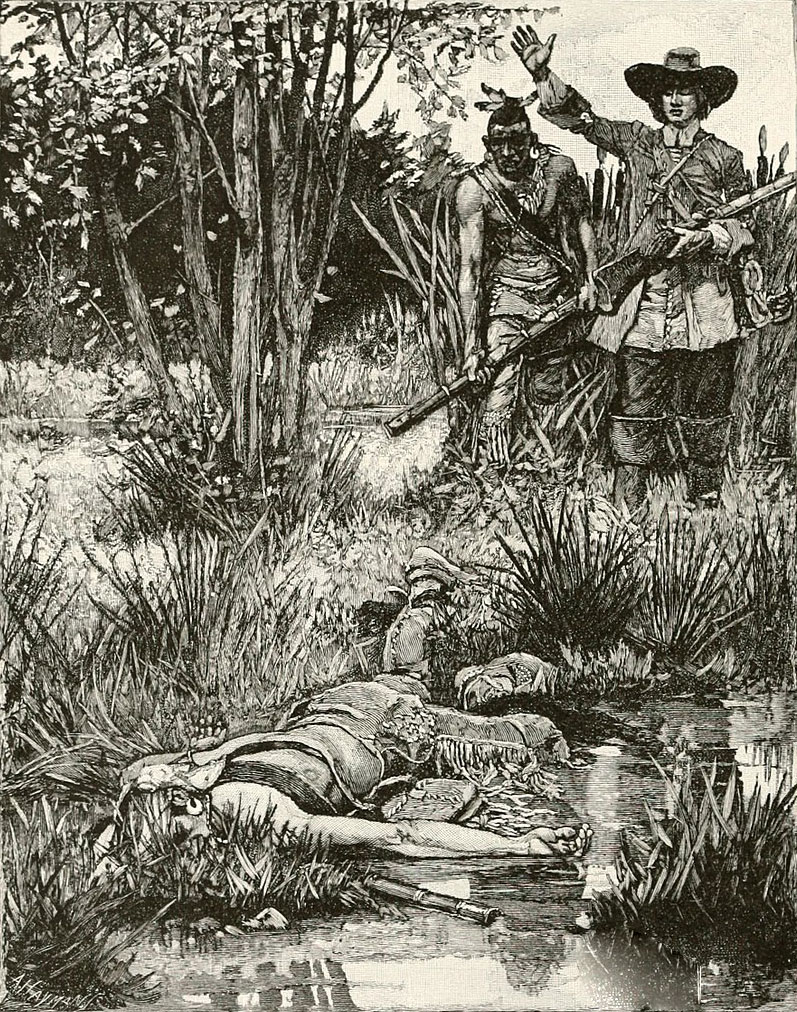

The war lapped over into New York, when Philip took some of his warriors there, probably to refit and prepare for the spring campaign. He was attacked by the Mohawks who ambushed and routed the New England Native army. Although it was a severe blow to Philip, the raids and massacres continued against more than twenty English towns and villages in 1675-76. On March 12, they attacked Plymouth Plantation but were repelled. The war expanded throughout all the New England colonies until August 12, 1676, when a Christian Indian shot King Philip through the heart. The war had cost thousands of lives on both sides and made an indelible mark on the history of New England. During the war, natives of the praying towns were sent to Deer Island in Boston Harbor, suspected of disloyalty. Many died of disease and hunger throughout the war. Many native survivors of the war settled in northern New York. Wampanoag prisoners were enslaved, some shipped to the Caribbean islands, including Philip’s family. Historical markers related to the war dot the landscape today across New England, and many place names proudly display the name of Metacom and hearken back to his tragic attempt to drive out the English.

A stone marks the spot where King Philip fell

King Philip was shot and killed on August 12, 1676 by John Alderman, a Christian Indian, who was accompanied by Captain Benjamin Church (historic predecessor of the United States Army Rangers), and Captain Josiah Standish (son of Captain Myles Standish)

Image Credits: 1 King Philip (Wikipedia.org) 2 Massasoit (Wikipedia.org) 3 Old Indian Meeting House (Wikipedia.org) 4 Treaty (Wikipedia.org) 5 Ayres’ Inn Attack (Wikipedia.org) 6 Assawompset Pond (Wikipedia.org) 7 Attack on Settlers (Wikipedia.org) 8 Battle of Bloody Brook (Wikipedia.org) 9 Stone Marker (Wikipedia.org) 10 Death of King Philip (Wikipedia.org)