“Truly, truly I say to you, an hour is coming, indeed it’s here now, when the dead will hear my voice—the voice of the Son of God. And those who listen will live.”

—John 5:25, Inscribed on the grave of T. E. Lawrence

“Lawrence of Arabia” Born in Wales,

August 16, 1888

![]() .E. Lawrence, a second son, was born in Tremadog, Canarvonshire, Wales, in a house named Gorphwysfa (now Snowdon Lodge), August 16, 1888. His parents never married, his father (Sir Thomas Chapman) having run off with the governess of his daughters, had five children with the governess, herself illegitimate, and adopted the surname Lawrence to call themselves. Such beginnings do not seem like a recipe for dangerous adventures, best-selling authorship, archaeological brilliance, national hero status and world renown. Thomas E. Lawrence refused to be confined by his environmental circumstances and social handicaps.

.E. Lawrence, a second son, was born in Tremadog, Canarvonshire, Wales, in a house named Gorphwysfa (now Snowdon Lodge), August 16, 1888. His parents never married, his father (Sir Thomas Chapman) having run off with the governess of his daughters, had five children with the governess, herself illegitimate, and adopted the surname Lawrence to call themselves. Such beginnings do not seem like a recipe for dangerous adventures, best-selling authorship, archaeological brilliance, national hero status and world renown. Thomas E. Lawrence refused to be confined by his environmental circumstances and social handicaps.

Gorphwysfa in Tremadog, Canarvonshire, Wales, birthplace of T.E. Lawrence

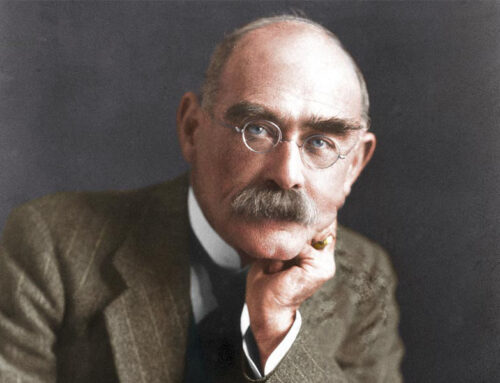

Thomas Edward Lawrence (1888-1935) was a British archaeologist, army officer, diplomat, and writer, better known as “Lawrence of Arabia”

Thomas—nicknamed Ned, he preferred just his initials T.E.—spent his teenage years in Oxford, where his father finally settled his second family, after living in Wales, Scotland, Brittany, and Jersey. His father inherited the baronetcy of Chapman in Ireland, never having divorced or married beneath his station. Ned spent his youth exploring castles and old churches, collecting artifacts, and reading history books. He “read history” at Jesus College at Oxford, and in 1908, bicycled 2,200 miles through France, becoming so fluent in that language that people thought he was a Frenchman. He clambered over and studied castles wherever he went. The following year he walked more than a thousand miles through Ottoman Syria studying Crusader castles, a fascination with military architecture which never left him.

The second quadrangle of Jesus College, Oxford, where Lawrence studied history

David George (D.G.) Hogarth (1862-1927) of the British Museum took a special interest in Lawrence. Pictured here are (L-R) Lawrence, Hogarth, and Guy Payan Dawnay at the Arab Bureau of Britain’s Foreign Office, Cairo, May 1918

So impressed with Lawrence was D.G. Hogarth of the British Museum, that he awarded the budding archaeologist with a stipend to study Middle Eastern archaeological digs and travel far and wide with the greatest scholars of that discipline. He learned to speak Arabic and was given access to unexplored regions, strategic towns, and important military outposts that the British government would find useful in the coming World War.

T.E. Lawrence (L) and Leonard Woolley (R) in Carchemish (on the frontier between Turkey and Syria), with an Early Hittite artifact found during their archaeological research

Both cultures, for the most part, kept to the terms of the treaties, fulfilling the requirements of justice for criminal behavior by Englishmen or Wampanoag. Also during the treaty years, many more colonists arrived, increasing the number of Englishmen not members of the church, or loose and unattached on the frontier, or just looking for “the main chance” to prosper at the native’s expense, especially in land acquisition. Puritans, but not Separatists, founded the Massachusetts Bay Colony to the north of Plymouth, which exceeded the population and geography of Plymouth within a short period of time. By 1675, one hundred years before the War for American Independence, the English population of New England exceeded 65,000, in 110 towns, with added colonies of Connecticut and Rhode Island, while the major native tribes like the Massachusetts, Nipmucs, Narragansetts, and Wampanoags could probably count about 10,000. They all spoke Algonquian dialects.

Indian assault on Ayres’ Inn as part of King Philip’s War, August 4, 1675

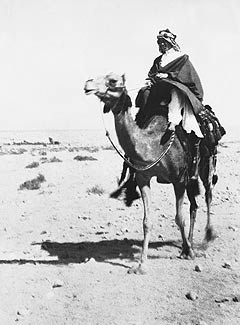

After hostilities began, the British “Arab Bureau of Middle East Intelligence” recruited T.E. and made him a Lieutenant to draw maps, help with strategic planning, interrogate Turkish prisoners, and eventually to serve as a liaison between Arab tribal chiefs and the British high command in Cairo. He provided money and guns to the followers of Prince Faisal and joined his Arab revolt against the Turks. Lawrence helped plan and lead hit-and-run attacks and raids behind enemy lines, keeping the Damascus to Medina Railway inoperable. To the admiring Bedouins he became “Amir Dynamite.” His guerilla forces captured Aqaba, a major point along the Gulf of Aqaba, just off the Red Sea. British officials promoted Lawrence to Lt. Colonel. He continued to lead Arab forces in conjunction with the offensive by General Allenby to capture Jerusalem, and his amazing exploits were written up and promoted by an American war correspondent named Lowell Thomas. Soon the whole world was talking about “Lawrence of Arabia.”

Lawrence riding a camel at Aqaba, 1917

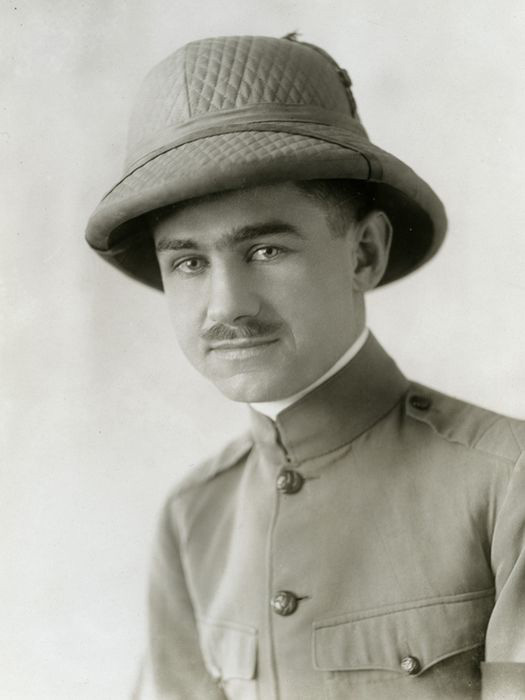

Lowell Jackson Thomas (1892-1981), an accredited war correspondent—as photographed during his time in Arabia—was influential in publicizing the life and exploits of Lawrence

T.E. Lawrence received numerous wounds, none fatal, leading the Bedouin to believe he could not be killed. He adopted native dress and customs, assured that when Damascus was taken, the combined Arab forces would be able to build their own state apart from the Ottoman Turks. Unknown to Lawrence, the French and British diplomats had already carved up the Middle East, with a wholly different role than the divided and quarreling Arab tribes had been promised. Imperial politics always took precedent over temporary military alliances, especially among desert tribal people with little experience in international diplomacy. He showed up at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919 in Arab robes, but was given no notice nor credence as France and Britain carved up the Middle East, with little reference to tribal differences or geographical boundaries. Colonel Lawrence, in 1920, became an advisor and friend of Winston Churchill for a year and made numerous trips to the Middle East, hoping Churchill’s vision would be the one that prevailed.

The delegation of Prince Faisal of Syria to the 1919 Paris Peace Conference: (L-R) Rustum Haidar, Nuri as-Said, Prince Faisal (front), Captain Pisani (rear), T. E. Lawrence, Faisal’s slave (name unknown), Captain Hassan Khadri

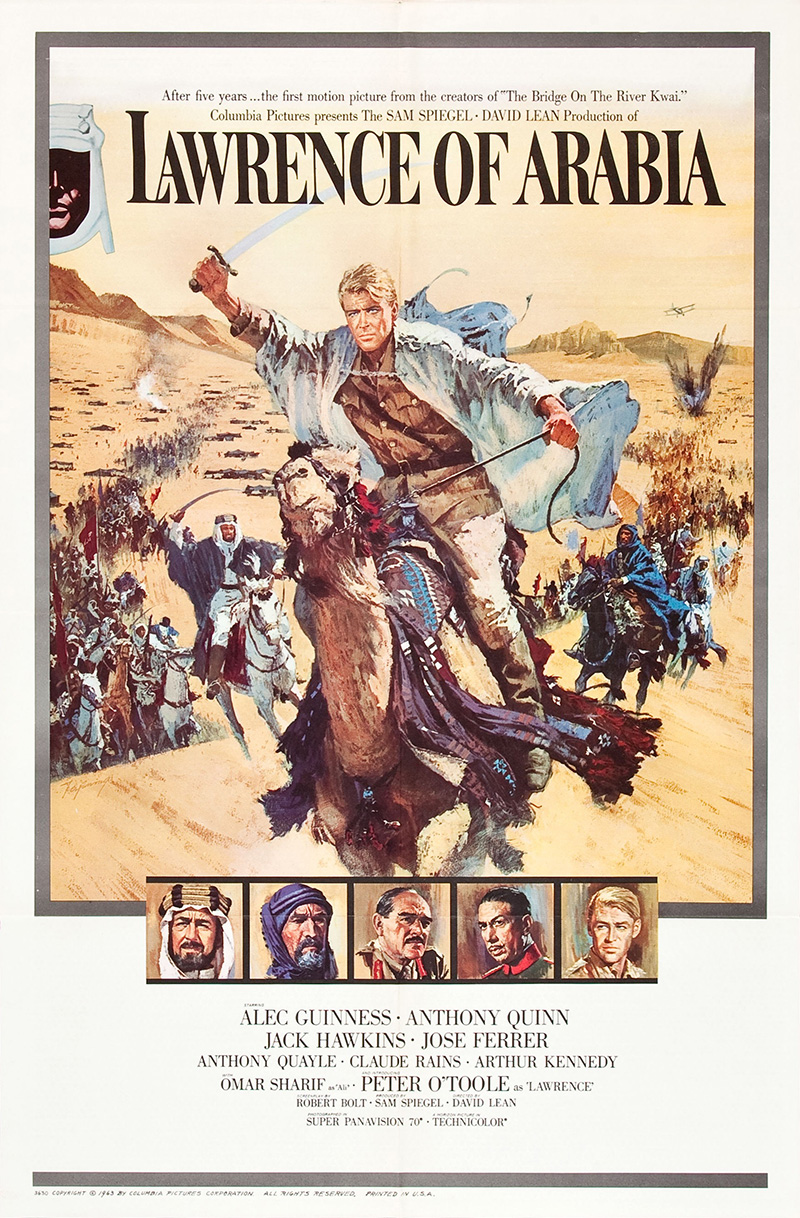

Sick of government and bureaucracy, Lawrence enlisted as a private in the RAF as a mechanic in 1922, under a false name. That same year he completed his memoirs of the war, entitled The Seven Pillars of Wisdom. Britannica describes his best-selling autobiography as an action-packed narrative of Lawrence’s campaigns in the desert with the Arabs. The book is replete with incident and spectacle, filled with rich character portrayals and a tense introspection that bares the author’s own complex mental and spiritual transformation. Though admittedly inexact and subjective, it combines the scope of heroic epic with the closeness of autobiography. His story came to the silver screen in 1962 with Lawrence of Arabia starring Peter O’Toole and an all-star British cast. It was nominated for ten Oscars and won seven, and is widely considered “one of the greatest and most influential films ever made.” He continued writing the rest of his life, becoming a friend of some of the greatest and most gifted authors of the century.

Theatrical release poster for the monumental 1962 film Lawrence of Arabia, chronicling the life and adventures of T.E. Lawrence

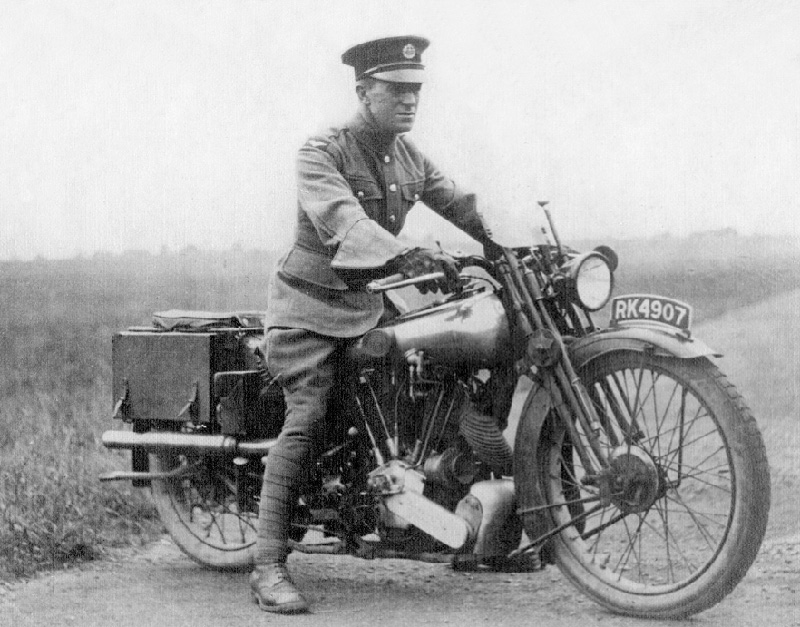

Lawrence on his Brough Superior motorcycle in 1925 or 1926

T.E. Lawrence spent much of his time in the interwar period working on developing air-sea rescue craft for the RAF and racing Brough Superior motorcycles. He died in a motorcycle accident in 1935 at the age of forty-six, and is buried in a churchyard in Moreton, England, where he lived. Two of his brothers had been killed in the trenches of WWI in France, leaving one brother and his mother to mourn his loss. His reputation, however, knew no geographical boundaries. His funeral was attended by Winston Churchill, Lady Astor and the writer E.M. Forester, a friend and inspiration. The movie, twenty-seven years later, made him once again an international sensation.

The final resting place of T.E. Lawrence at St Nicholas’ Church, Moreton, Dorset, England

Image Credits: 1 Gorphwysfa (Wikipedia.org) 2 Lawrence in Arabian attire (Wikipedia.org) 3 Jesus College, Oxford (Wikipedia.org) 4 Lawrence, Hogarth, Dawnay (Wikipedia.org) 5 Lawrence in Carchemish (Wikipedia.org) 6 Lawrence on Camel (Wikipedia.org) 7 Lowell Thomas (Wikipedia.org) 8 Faisal Delegation in Paris (Wikipedia.org) 9 Lawrence of Arabia movie poster (Wikipedia.org) 10 Lawrence on his motorcycle (Wikipedia.org) 11 Grave of Lawrence (Wikipedia.org)