“Hear, my son, and accept my words, that the years of your life may be many.” —Proverbs 4:10

Crazy Horse Surrenders, May 6, 1877

![]() ensus data, missionary tales, soldiers’ letters and diaries, government documents of all sorts, photographs, and the impressions of enemies have been most often used in the past to tell the stories of the Plains Indians of America. On rare occasions, Indian family members have recorded the oral history of their kin-folk, which reveals the real character, culture, religion, and impressions of a particular clan or individual that lived in the past. All the above resources are available for the life of the greatest Lakota Sioux warrior, Crazy Horse.

ensus data, missionary tales, soldiers’ letters and diaries, government documents of all sorts, photographs, and the impressions of enemies have been most often used in the past to tell the stories of the Plains Indians of America. On rare occasions, Indian family members have recorded the oral history of their kin-folk, which reveals the real character, culture, religion, and impressions of a particular clan or individual that lived in the past. All the above resources are available for the life of the greatest Lakota Sioux warrior, Crazy Horse.

The man known as Crazy Horse was the third of that name in three generations. Among the Lakota, one’s given name could change more than once in a lifetime, if particular events warranted a new name. And so it was with Ca-oha, “Among the Trees,” named by his father “Crazy Horse” and his mother “Rattling Blanket Woman” when he was born, probably about 1840. As a teenager, Ca-oha was on a hunt alone, when he came across a Shoshone warrior, part of a raiding party, killing a Lakota woman. Ca-oha charged the enemy warrior on horseback and killed him with his club, then rode up into the hills and hid until nightfall. He eluded the Shoshone and rode home undetected. His father realized his brave son would now need a new name and chose to give up his own. The tribe celebrated the newly endowed Crazy Horse as a warrior, and for the next three decades, he would not disappoint them, or betray their trust.

An alleged photo of Crazy Horse (c. 1840-1877) in 1877, though whether he was ever photographed is disputed

One of several similar treaties between the United States government and various tribes in the 1850s, the Treaty of Traverse des Sioux was signed on July 23, 1851, at Traverse des Sioux in Minnesota Territory between the United States government and the Upper Dakota Sioux bands

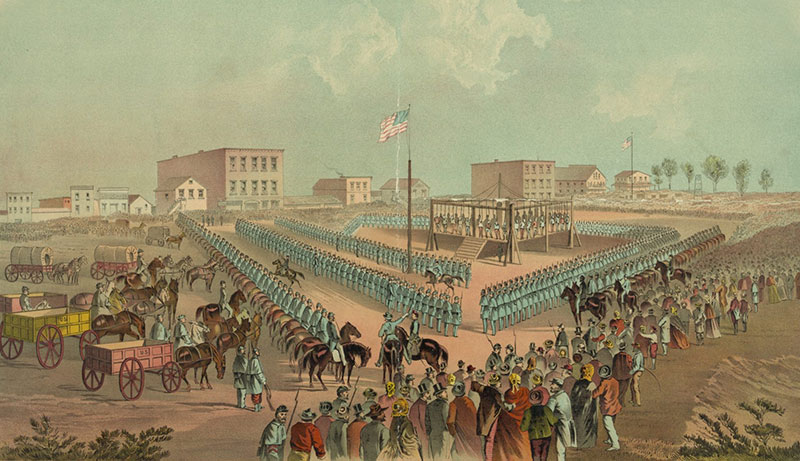

In the 1850s, the United States government cut treaties with various Plains tribes, forcing them on to reservations, but in return giving gifts to the leaders and providing food. Not all the natives accepted the welfare nor the geographical restrictions. With thousands of Americans moving westward and the discovery of gold in California and other places, Indian land was crisscrossed with wagon trains of settlers, and with greedy miners and young men looking for “the main chance.” They sometimes slaughtered the buffalo and left them to rot. Conflicts with the natives became inevitable, misunderstanding and cultural ignorance commonplace. In Minnesota in 1862, violence and resistance resulted in the hanging of thirty-eight Sioux warriors on order of Abraham Lincoln, which sent a message to the other clans that life on the Plains was going to change, or else.

The public hanging of thirty-eight Sioux Indians at Mankato, Minnesota, December 25, 1862, by order of President Abraham Lincoln for revolt against the government

In South Dakota, Crazy Horse and other tribal head-men decided they would defend their homes against the encroachment of the easterners. Crazy Horse led raids against army patrols and posts, looking to arm his warriors with more modern weapons. In 1865, south of the Dakotas, army attacks massacred Cheyenne women and children, so Crazy Horse gathered some of his warriors and set out to help the Cheyenne cut off the “Oregon Trail.”

An artist’s depiction of breaking camp at sunrise along the Oregon Trail

The Arapaho tribe also joined Crazy Horse as an ally after the U.S. soldiers massacred some of their families in an effort to keep them away from the miners and the settlers on the Oregon Trail. In 1866 the American Army built three new forts and added a thousand soldiers to the western command. Generals Sherman, Sheridan and Custer—three of the most destructive and notorious Union Generals from the War of Southern Independence—were soon sent west to “pacify the natives.” Scorched earth and repeating rifles would again accompany the blue-coats.

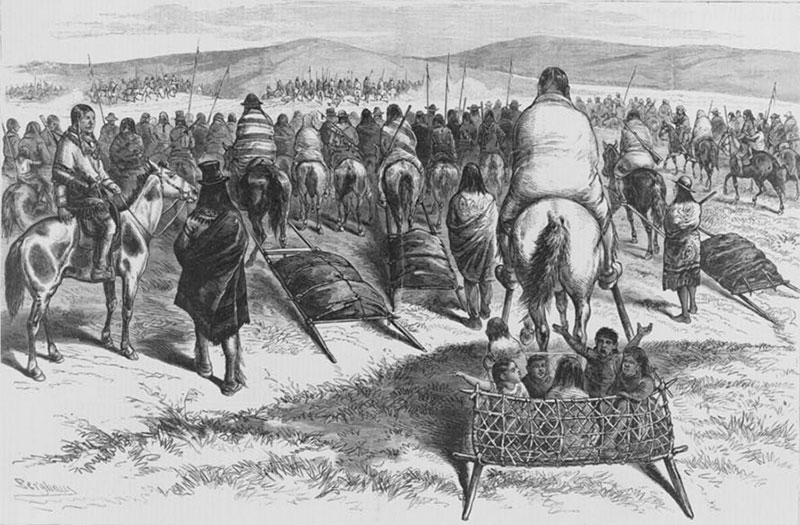

Custer leads United States Cavalry on an attack at the Cheyenne camp of Washita

That same year, Crazy Horse lured a combined infantry and cavalry detachment, led by Captain William Fetterman, into a trap from which no soldiers survived—the army’s worst defeat to a native force, up to that time. At the “Wagon Box Fight,” Crazy Horse’s more than 1,000 warriors faced breech-loading rifles for the first time, taking unusually heavy casualties in defeat. In the “Great Sioux War” of 1875-76, Crazy Horse and more than fifteen hundred Lakota and Cheyenne fought a thousand infantry and cavalry of General George Crook along with his three hundred Shoshone and Crow allies in the Battle of the Rosebud and later at the Little Big Horn. Colonel George Armstrong Custer’s command lost two-thirds of the regiment killed and wounded, including the gallant Custer. While Crazy Horse’s leadership at that battle is lesser known, native participants claimed that his fearlessness and aggressive attacks made a powerful addition to the tactics that succeeded in annihilating the 7th Cavalry troopers. In January of 1877, Crazy Horse led his Lakota warriors for the last time into battle, in an engagement in Montana. Weakened by the following winter, the Lakota band that followed Crazy Horse decided to turn themselves in at the Red Cloud Agency at Fort Robinson, Nebraska. Along with fellow warriors He Dog, Little Big Man, and Iron Crow, Crazy Horse met with authorities to arrange a formal surrender on May 5, 1877. After a controversial parley at Fort Robinson in September of that year, a scuffle broke out and a guard bayonetted Crazy Horse to death.

A marker showing the spot where Crazy Horse was killed on September 5, 1877

Crazy Horse and his people on their way from Camp Sheridan to surrender to General Crook at Red Cloud Agency, Sunday, May 6

A number of controversies and questions surround the life and death of Crazy Horse, but undisputed is his earned reputation as a great leader of men, a warrior of uncommon bravery, and an ardent defender of the Plains Indians and their way of life. A monumental carving of Crazy Horse is still under construction between Custer and Hill City, South Dakota. When complete, it will be the world’s largest sculpture, his head twenty-seven feet taller than the presidential counterparts a few miles away at Mount Rushmore.

The Crazy Horse monument under construction in South Dakota

- For an interesting, enjoyable, and informative, but not particularly objective, account by descendants of Crazy Horse, read Crazy Horse: the Lakota Warrior’s Life and Legacy, 2016.