“He has told you, O man, what is good; and what does the Lord require of you but to do justice, and to love kindness, and to walk humbly with your God?” —Micah 6:8

The Plessy v. Ferguson Case Decided, May 18, 1896

![]() upreme Court rulings look like the Friday night boxing card between two pugilists, usually destined for future anonymity, but temporarily the main event for entertainment. And so it is with many of those rulings, soon forgotten, unenforceable, or irrelevant in the larger scheme of American history. A few cases actually change history, and are known as “landmark decisions.” While Mohammed Ali v. Joe Frazier, or Evander Holifield v. Mike Tyson drew international attention in the boxing world for a few weeks or months, the Supreme Court Case of Plessy v. Ferguson confirmed the states’ right to racial segregation in public places, including schools, for more than fifty-eight years. In 1954, the SCOTUS overturned the ruling as it related to public education. Today, Plessy is cited by some to call into question the use of precedent in the basic practices of the Court. The legal confrontation resembled a boxing match of epic proportion.

upreme Court rulings look like the Friday night boxing card between two pugilists, usually destined for future anonymity, but temporarily the main event for entertainment. And so it is with many of those rulings, soon forgotten, unenforceable, or irrelevant in the larger scheme of American history. A few cases actually change history, and are known as “landmark decisions.” While Mohammed Ali v. Joe Frazier, or Evander Holifield v. Mike Tyson drew international attention in the boxing world for a few weeks or months, the Supreme Court Case of Plessy v. Ferguson confirmed the states’ right to racial segregation in public places, including schools, for more than fifty-eight years. In 1954, the SCOTUS overturned the ruling as it related to public education. Today, Plessy is cited by some to call into question the use of precedent in the basic practices of the Court. The legal confrontation resembled a boxing match of epic proportion.

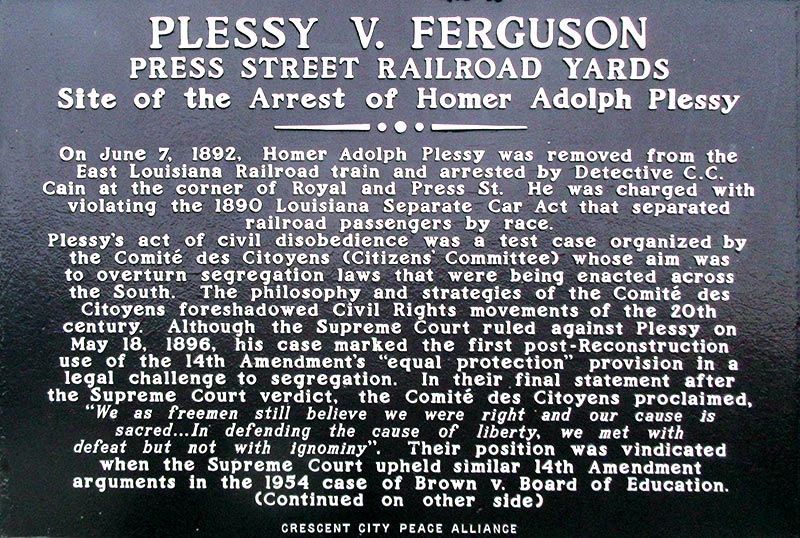

In 1892, Homer Plessy, an “octoroon” (1/8th black), virtually white in color, as were many creoles in Louisiana, challenged that state’s law prohibiting blacks and whites to sit in the same railroad car. He bought a first class ticket and sat in the “whites only” car of the Louisiana Railway out of New Orleans. A mixed race organization, The Committee of Citizens, had already notified the railway that Plessy was a creole with a black great-grandparent, and hired a detective to arrest him, to assure that he was charged with breaking the law they wanted changed. The entire case was a set-up to challenge the Louisiana law segregating races in railroad cars. (Roe v. Wade (1973) and the State of Tennessee v. Thomas Scopes (1925) trials were orchestrated in a similar fashion by the ACLU and in future civil rights cases by the NAACP.)

Homer Adolph Plessy (born Homère Patris Plessy; c. 1862/1863-1925), plaintiff in Plessy v. Ferguson

|

|

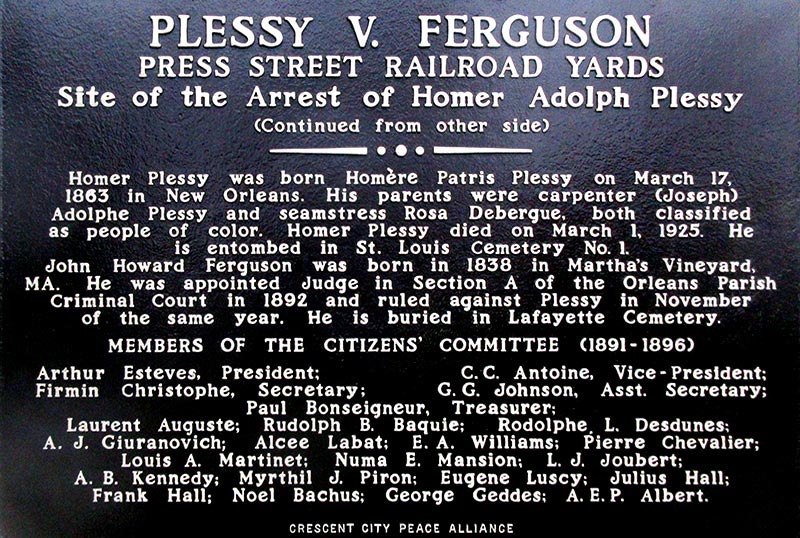

A placard (front and back) marks the place in New Orleans where Homer Plessy was arrested on June 7, 1892, which incident eventually led to Plessy v. Ferguson

Cases tried by the Supreme Court begin at the local or state level and work their way through appeal to SCOTUS. The Supreme Court chooses what cases they want to try. In recent years they have used what they call “the rule of four” to determine if they will look at a case—in other words, if at least four justices out of the nine think the court should try a particular case. The Plessy case, therefore, began in the state of Louisiana criminal court, in which Judge Ferguson ruled against him. Plessy’s attorneys argued that the Louisiana law was unconstitutional under the 14th Amendment which granted citizenship to ex-slaves and assured equal protection under the law for all citizens.

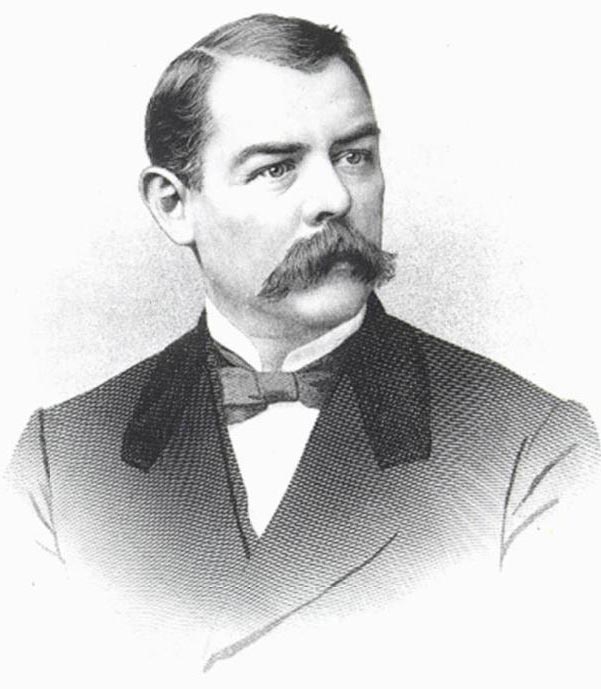

Albion Winegar Tourgée (1838-1905) was an American soldier, lawyer, writer, politician, and diplomat, best known for litigating Plessy v. Ferguson

The state Supreme Court held that segregation based on race was within the bounds of the law since racial prejudice was not created by law and could not be legislated away. They cited precedential cases from Massachusetts and Pennsylvania, where racial discrimination had been upheld in similar types of cases regarding both education and railway cars, and which the “order of Divine Providence” was also cited. The Committee then appealed to the Supreme Court of the United States.

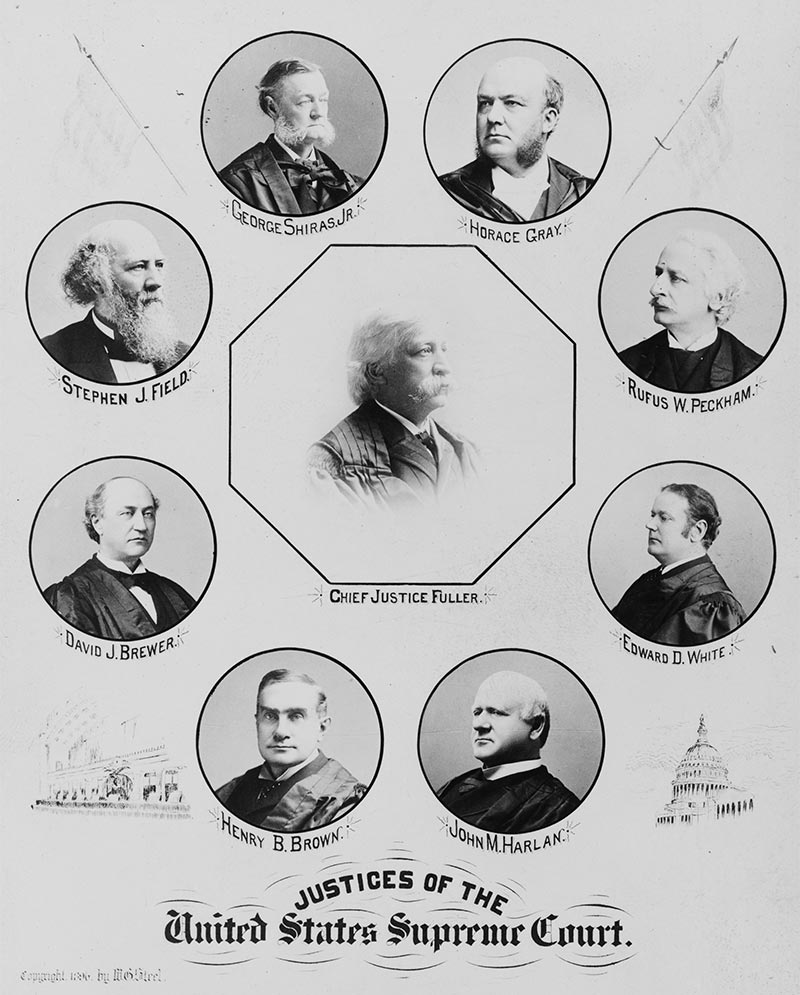

Justices of the United States Supreme Court in 1896: Chief Justice Fuller, Horace Gray, Rufus W. Peckham, Edward D. White, John M. Harlan, Henry B. Brown, David J. Brewer, Stephen J. Field, and George Shiras, Jr.

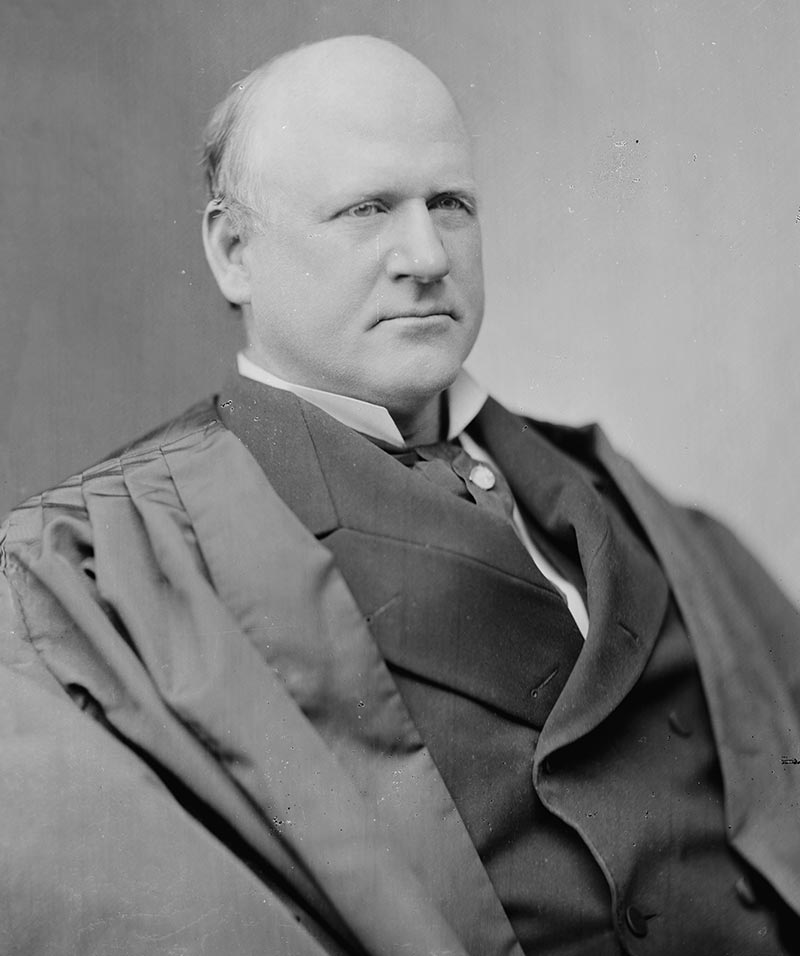

The Supreme Court heard similar arguments and decided 7-1 in favor of the State of Louisiana, that the train-car segregation laws were not unconstitutional. The majority declared that equal protection under the law was not designed to prohibit social or racial discrimination. The races could be equal but separate. The one dissenting justice, John Marshall Harlan, argued that the Louisiana Law indeed implied that black people were inferior, and that that was unconstitutional. So Homer Plessy lost his case and paid the $25.00 fine, but the results had far-reaching implications.

Justice John Marshall Harlan (1833-1911) became known as “The Great Dissenter” due to his regular dissent particularly in civil rights cases, as he did in Plessy v. Ferguson

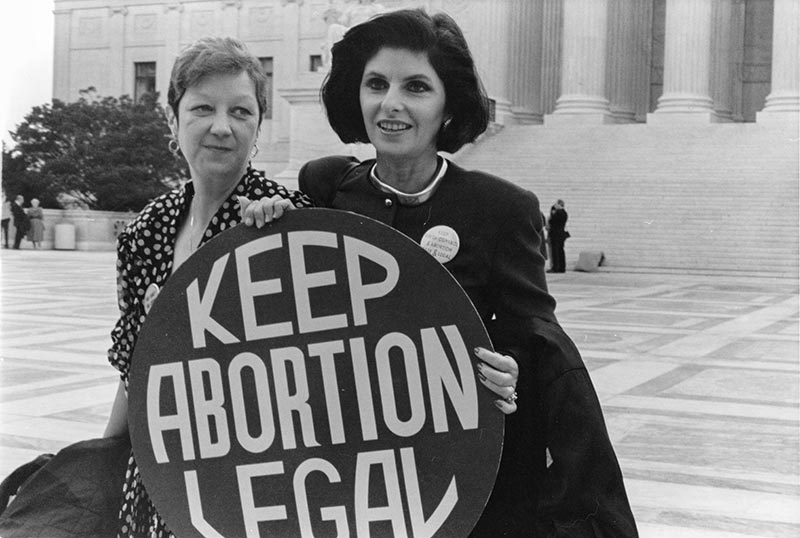

The “separate but equal” doctrine affirmed all racial restriction laws in the United States from the Louisiana Railway Law to the Boston, Massachusetts school districts. A groundswell of new “Jim Crow” legislation occurred, especially in the South, disenfranchising poor voters in some districts, re-establishing color lines in others, in transportation, school funding and drinking fountains. Plessy marked a return, to some extent, to rightful state authority affirmed in the 10th Amendment, restricted after the Civil War. In 1954 in Brown v. The Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, the Supreme Court overturned Plessy v. Ferguson to declare that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional even if they were otherwise equal in every way. In a 9-0 decision the Court declared that separate was unequal by definition. By expanding the meaning of the 14th Amendment to apply to all sorts of “Civil Rights,” the Court eventually used the same Amendment to issue the Roe v. Wade case in 1973. It remains to be seen if SCOTUS will change its mind on such a use of the 14th Amendment.

Norma McCorvey (left) who was Jane Roe in the 1973 Roe v. Wade case, with her attorney, Gloria Allred, outside the Supreme Court in April 1989, where the Court heard arguments in a case that could have overturned the Roe v. Wade decision