“These six things doth the Lord hate: yea, seven are an abomination unto him… hands that shed innocent blood… an heart that deviseth wicked imaginations…” —Proverbs 6:16-18

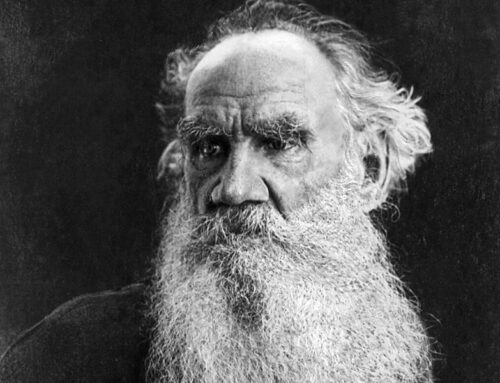

John Brown the Domestic Terrorist, 1856

![]() he turbulent decade of the 1850s witnessed the attempts by the people of Kansas and Nebraska (1854) to organize formally as territories, looking forward to eventual statehood. Southern congressmen opposed their entry as territories since they were north of Missouri’s southern border and therefore could not allow slavery. Stephen Douglas of Illinois brokered the compromise that would allow the two new territories to organize, but the slavery issue would be decided by popular vote of the citizens themselves. Since a constitution would have to be drawn up, pro-slavery and anti-slavery forces sprang into action to persuade the population to vote in their favor. New settlers poured relentlessly into the territories from other states, both slave and free. Among the anti-slavery crowd would be a cadre of terrorists led by a New York abolitionist named John Brown. His solution to the problem—murder pro-slavery settlers before they could exercise influence at the polls.

he turbulent decade of the 1850s witnessed the attempts by the people of Kansas and Nebraska (1854) to organize formally as territories, looking forward to eventual statehood. Southern congressmen opposed their entry as territories since they were north of Missouri’s southern border and therefore could not allow slavery. Stephen Douglas of Illinois brokered the compromise that would allow the two new territories to organize, but the slavery issue would be decided by popular vote of the citizens themselves. Since a constitution would have to be drawn up, pro-slavery and anti-slavery forces sprang into action to persuade the population to vote in their favor. New settlers poured relentlessly into the territories from other states, both slave and free. Among the anti-slavery crowd would be a cadre of terrorists led by a New York abolitionist named John Brown. His solution to the problem—murder pro-slavery settlers before they could exercise influence at the polls.

John Brown (1800-1859) in May of 1859, months before his execution

Birthplace of John Brown in Torrington, Connecticut as it was in 1896. The home was lost to a fire in 1918.

Birthplace of John Brown in Torrington, Connecticut as it was in 1896. The home was lost to a fire in 1918.

John Brown (1800-1859), grew up primarily in northeastern Ohio and western Pennsylvania, opening a tannery, following in his father’s footsteps. He married at 20, his wife dying twelve years later having borne him seven children. His second wife, seventeen-year-old Mary Anne Day, bore him fourteen more children. He never touched alcohol, tobacco, tea or coffee, and memorized great swaths of Scripture. Brown committed himself to the abolition of slavery, and his tannery in Crawford County, Pennsylvania (1825-35) provided a way station for the “underground railroad.” Seven of Brown’s sons would join him in his crusade to end slavery.

Mary Anne Brown, née Day (1816-1884), wife of John Brown with two of their daughters

An 1865 photograph of John Brown’s tannery

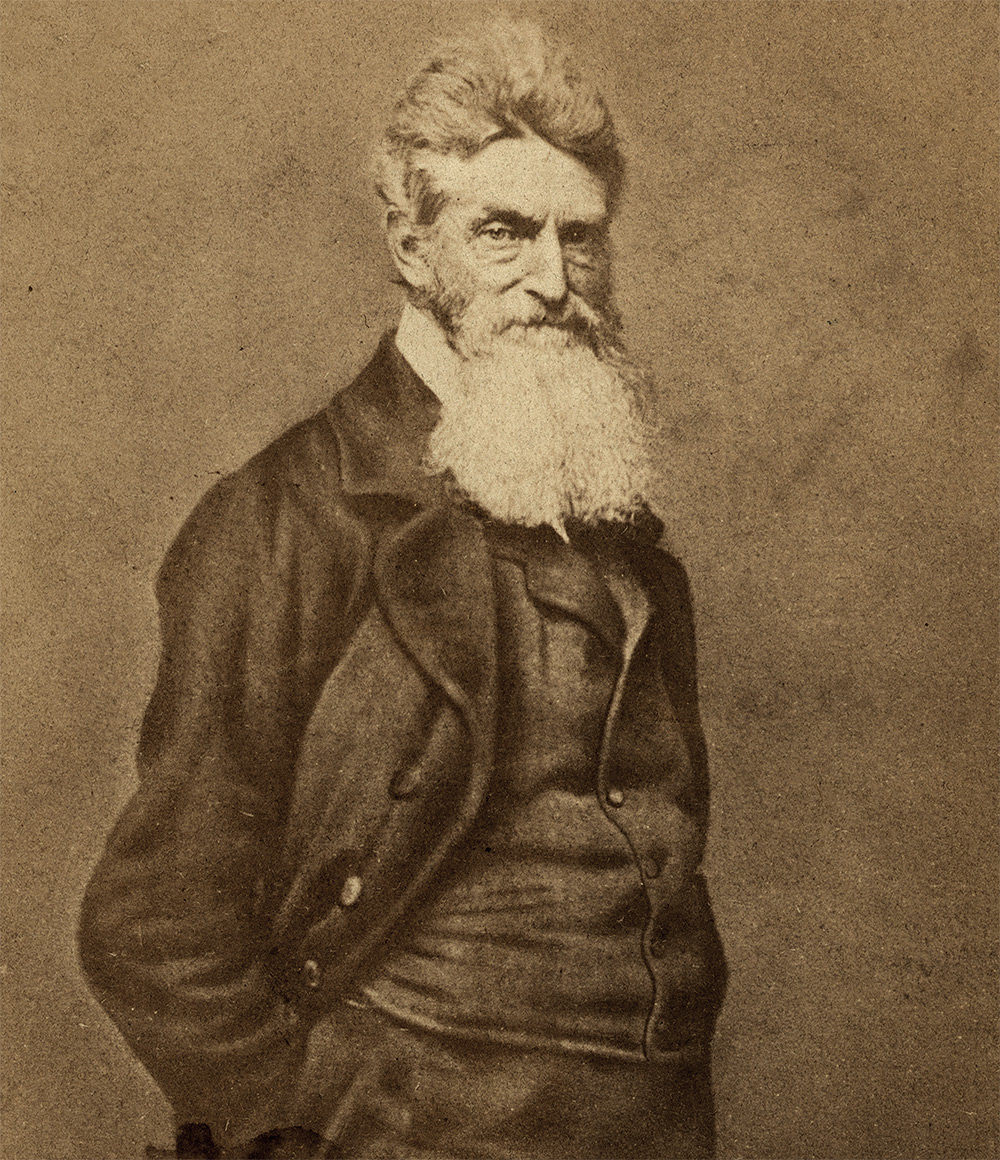

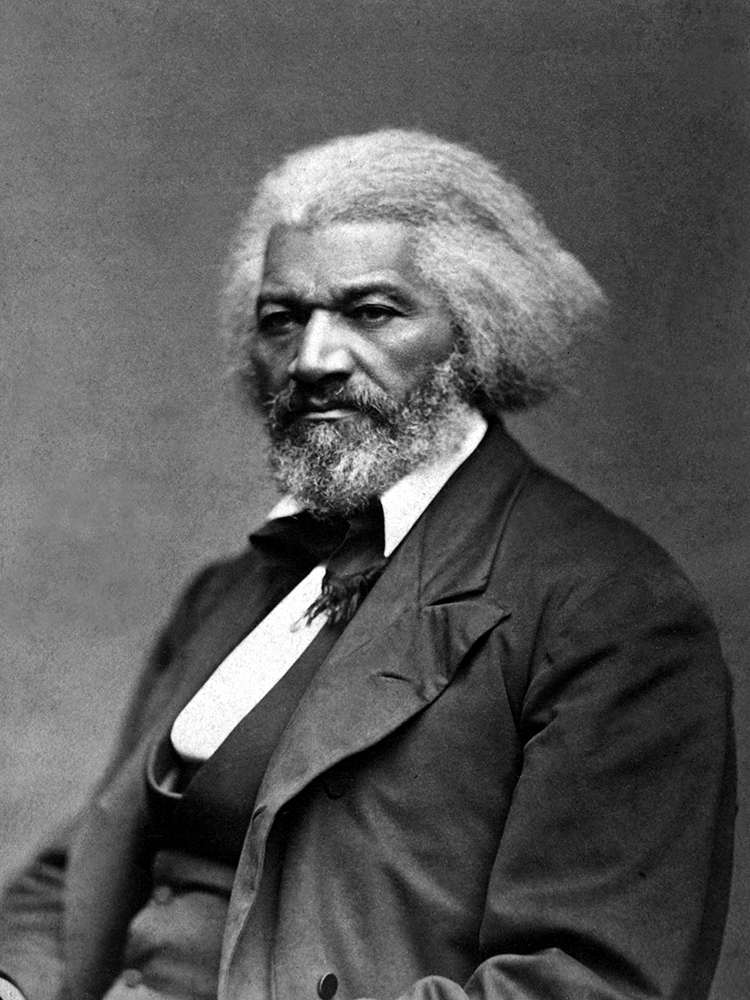

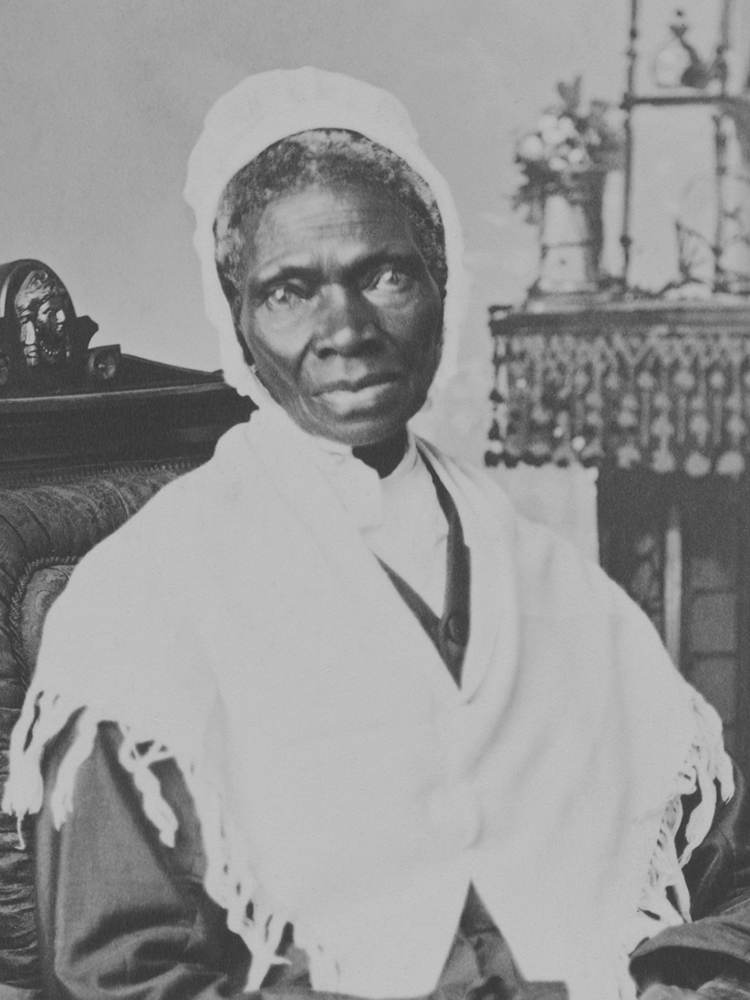

In 1836, Brown moved his family back to Ohio, where he continued an old habit of borrowing money to finance his business interests, losing his investments to over-reaching speculation and business failure, and moving on just ahead of his creditors. Brown declared bankruptcy in 1842. Likely the most crucial period of John Brown’s sojourn from failed business ventures to abolitionist terrorist came during his four years in Springfield, Massachusetts, where he joined the church foremost in the abolitionist movement, and where he spent many hours listening to and talking with Frederick Douglass, Sojourner Truth, and wealthy New England abolitionists—future financiers of his deadly schemes. By 1850, John Brown established his final home on land purchased from multi-millionaire abolitionist Gerritt Smith, in North Elba, New York.

John Brown’s farmhouse in North Elba, New York built on land purchased from multi-millionaire abolitionist Gerritt Smith

Frederick Douglas (1817-1895) was an American abolitionist, writer, and statesman

Sojourner Truth (c. 1797-1883) born Isabella Baumfree, was an American abolitionist and women’s rights activist

In the year following the Kansas-Nebraska Act, John Brown and five of his sons and a son-in-law moved to Osawatomie, Kansas Territory, with wagon loads of guns and ammunition, determined to make a difference in the civil war that seemed to be breaking out there and known to history as “Bloody Kansas.” Many southerners and northerners calculated that slavery would come to an end peaceably over time and that compensated emancipation would be the route followed, as had been the case in all the other western nations that had abolished the institution. The more radical wing of the abolitionist movement in New England and various pockets of supporters in other northern states, demanded instant abolition by any means necessary and at whatever human cost. As in most such revolutionary groups in history—usually representing a tiny minority of blood-thirsty radicals—the ends justified the means.

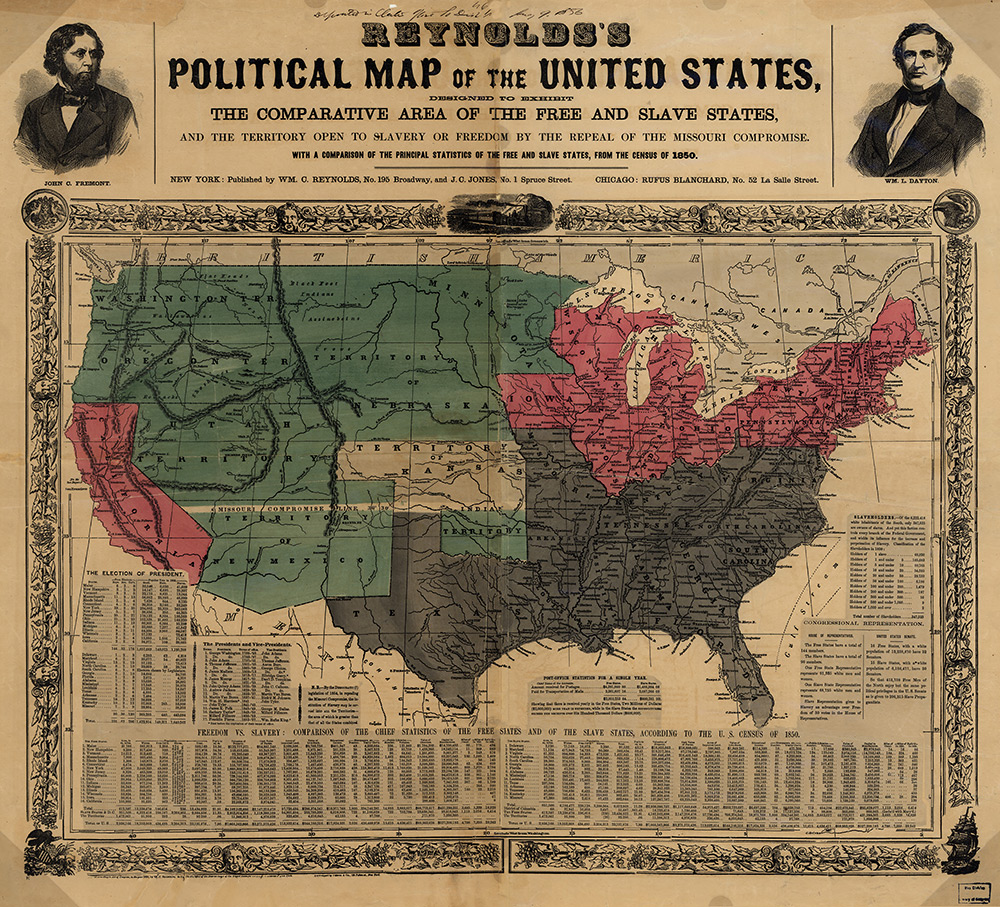

An 1856 map showing free states in pink, slave states in grey, territories in green, and Kansas in white

An 1856 map showing free states in pink, slave states in grey, territories in green, and Kansas in white

The Free-State advocates in Kansas, entering by wagon train loads from New England, New York, and Ohio, established strongholds in Lawrence and Topeka. The Slave-State advocates, mostly from the adjacent State of Missouri, held sway in Lecompton and scattered towns and farms around the territory. On May 21, 1856, pro-slavery settlers, led by a Federal Marshall and the Sheriff of Douglas County, who had earlier been shot in Lawrence trying to serve warrants, returned to that town, wrecked two abolitionist newspapers and burned down the Free-State Hotel. Partly in retaliation, partly in a previously decided commitment to “direct action,” John Brown, his sons and several other anti-slavery settlers set out in the dead of night on May 24, armed with pistols, rifles and swords, to visit the homes of men they suspected of pro-slavery sympathies. They descended on the homes along Pottawattamie Creek, hauling fathers and sons from their beds and hacking them to pieces with swords, while their women folk screamed and begged for mercy. Before the new day dawned, they had murdered five men from three different families and set fire to a civil war in Kansas that would not really end until 1865. Brown’s gang fought several more battles in Kansas before fleeing eastward with a price on their heads by the territorial government.

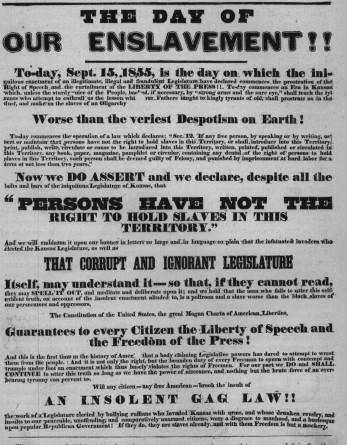

An 1855 Kansas free-state poster

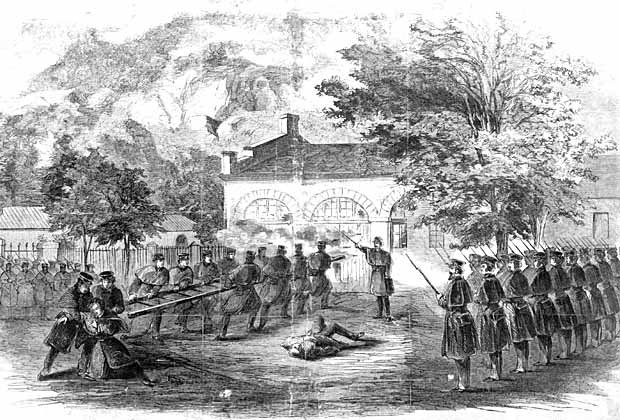

U.S. Marines under the command of Robert E. Lee surround the Harper’s Ferry engine house where Brown and his entourage took cover

Over the next three years Brown collected more killers and weapons, as well as financing from certain Unitarian and Congregationalist ministers, prominent intellectuals and millionaires in New England. In 1859 he led his gang into Virginia at Harper’s Ferry, murdered a free black man, and failed to raise the revolution he had envisioned. In the end, Brown was hanged for inciting revolution against the sovereign state of Virginia. Today, his home in Elba and the historic sites at Harper’s Ferry are National shrines of honor and glory to abolitionist John Brown. Both the massacre at Pottawatomie Creek and the failed attack on Harper’s Ferry are prominent in the FBI lists of historic domestic terrorist attacks in the United States.

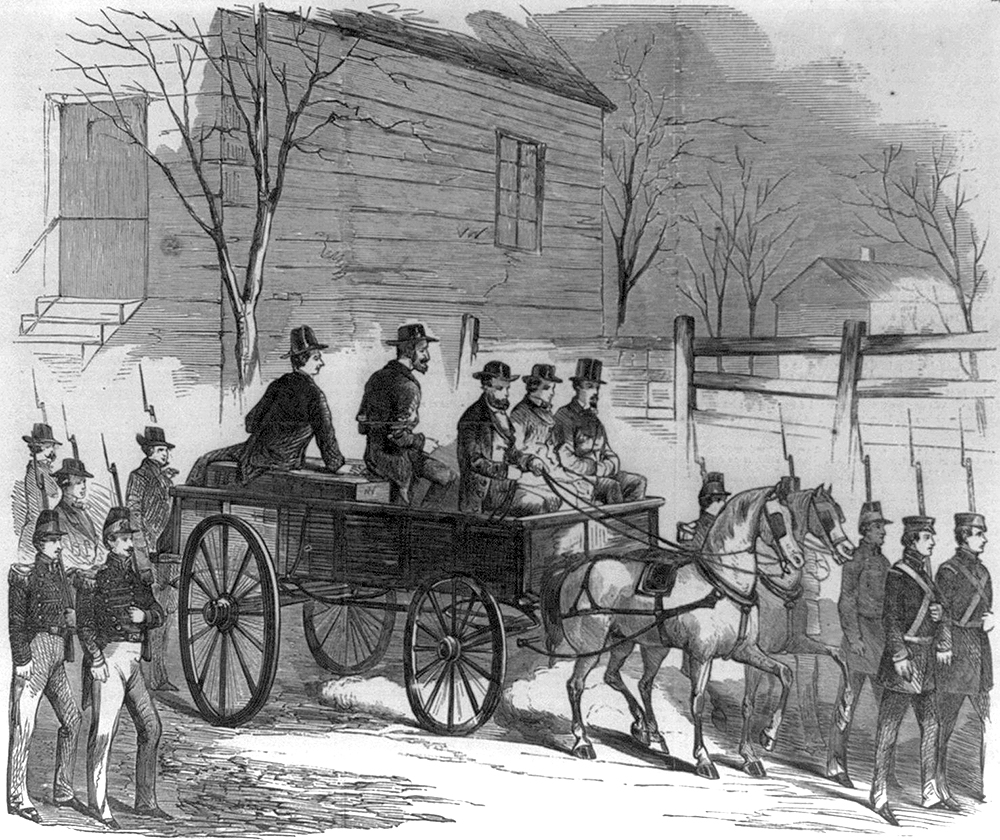

Brown rides in the back of a wagon on his own coffin en route to his execution