“If the foundations be destroyed, what can the righteous do?” —Psalm 11:3

Noah Webster Publishes the American Dictionary of the English Language, April 14, 1828

![]() f words are mere social constructs with no objective meaning, men and women bent on destroying Christian civilization and replacing it with subjective nonsense, myths and perversity will make great strides toward their goal. When words are defined by the social ethos of the moment, documents like the U.S. Constitution become nothing but historical curiosities, and biblical truth becomes irrelevant or evil by the lights of the humanistic cognoscenti. The ones who define the terms, win the argument. English, that most pliable and eclectic of all languages, reached its apogee of objective meaning with the publication of Noah Webster’s 1828 Dictionary.

f words are mere social constructs with no objective meaning, men and women bent on destroying Christian civilization and replacing it with subjective nonsense, myths and perversity will make great strides toward their goal. When words are defined by the social ethos of the moment, documents like the U.S. Constitution become nothing but historical curiosities, and biblical truth becomes irrelevant or evil by the lights of the humanistic cognoscenti. The ones who define the terms, win the argument. English, that most pliable and eclectic of all languages, reached its apogee of objective meaning with the publication of Noah Webster’s 1828 Dictionary.

Noah Webster (1758-1843)

Samuel Johnson (1709-1784)

The English-speaking world of the late 18th and early 19th Centuries relied almost exclusively on Samuel Johnson’s A Dictionary of the English Language. A product of nine years (1746-55) of painstaking collecting of common and uncommon English words, their etymological derivations, and use in written documents of the past, the dictionary reflected Johnson’s brilliant wit and humor as well as singular scholarship. It became the standard of definition, including the words used in the United States Constitution and the generation that founded the American Republic. In the new American context, however, the English language expanded exponentially with the use of native words, and the “language of liberty and independence.”

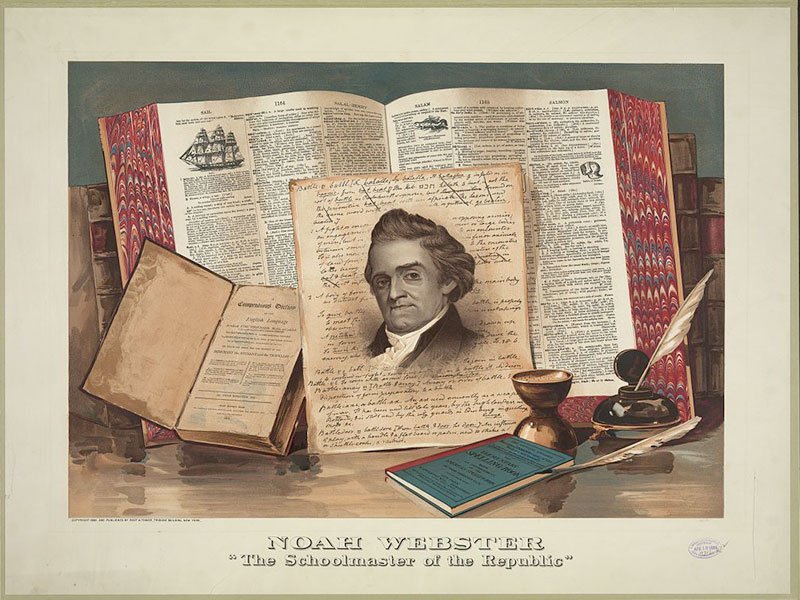

“Noah Webster, The Schoolmaster of the Republic,” print by Root & Tinker

One of the American founders, Noah Webster, set out to improve on Johnson’s work in the new American context, and in 1828 published American Dictionary of the English Language. Although he relied heavily on Johnson’s tome, Webster simplified arcane spellings and defined the words that reflected the New World realities. Webster avoided slang and vulgar wit, but relied heavily on the Bible, an unassailable source of objective truth, and the first thing “in which all children, under a free government, ought to be instructed.” Few books in history have so deeply established a standard of reference that undergird an entire civilization.

Connecticut-born Noah Webster descended from the first and one of the greatest of New England founders, Governor William Bradford. He graduated from Yale during the War for Independence and became one of the core defenders of the Federalist vision for America. His passion for educating American young people in the virtues and responsibilities of citizenship motivated him to write textbooks, including the best-selling blue-backed speller and others. Although just a peripatetic book-seller, he hob-knobbed with the writers of the Constitution in Philadelphia at the City Tavern, involving himself in the debates and discussions.

City Tavern in Philadelphia, est. 1773 and visited by the likes of George Washington, Paul Revere and others

As the father of American education, Webster pointed out that self-government and family government preceded any other type of government, and that the institution of the family needed to lay the foundation of the law and the gospel. For him the “Christian religion must be the basis of any government intended to secure the rights and privileges of a free people.” As one scholar has rightly asserted, “Noah Webster as a Christian scholar laid the foundation of etymology upon the Scriptures and his research into the origin of language stems from this premise.” His was a Christian philosophy of life, devoid of vulgarity and slang, but applicable to all Americans as they fulfilled the demands of a virtuous Republic with words that had specific meanings and did not change with the winds of fashion.

Image Credits: 1 Noah Webster (Wikipedia.org); 2 Samuel Johnson (Wikipedia.org); 3 City Tavern (Wikipedia.org); 4 Schoolmaster (Wikipedia.org)