“We are destroying speculations and every lofty thing raised up against the knowledge of God, and we are taking every thought captive to the obedience of Christ.” —2 Corinthians 10:5

Robert Barnes Burned at the Stake, July 30, 1540

![]() ome of the early leaders and martyrs of the Protestant Reformation have greater name recognition than Robert Barnes, but few lived as aggressive or colorful life than the Austin (Augustinian) Friar and Doctor of Divinity at Cambridge University. He attended the University of Louvain east of Brussels, a place already renowned for humanistic studies, especially the teaching of Erasmus, the brilliant Renaissance scholar. Barnes returned to Cambridge around the time of the publication of various tracts attacking unbiblical practices of the Catholic Church, written by fellow Augustinian friar Martin Luther in Saxony. A man at the level of Barnes’s education, and the widespread dissemination of Luther’s brazen and controversial writings surely came to the Englishman’s attention and probably discussion with his peers in the 1520s.

ome of the early leaders and martyrs of the Protestant Reformation have greater name recognition than Robert Barnes, but few lived as aggressive or colorful life than the Austin (Augustinian) Friar and Doctor of Divinity at Cambridge University. He attended the University of Louvain east of Brussels, a place already renowned for humanistic studies, especially the teaching of Erasmus, the brilliant Renaissance scholar. Barnes returned to Cambridge around the time of the publication of various tracts attacking unbiblical practices of the Catholic Church, written by fellow Augustinian friar Martin Luther in Saxony. A man at the level of Barnes’s education, and the widespread dissemination of Luther’s brazen and controversial writings surely came to the Englishman’s attention and probably discussion with his peers in the 1520s.

The city of Louvain, Belgium where Barnes attended the University of Louvain

The city of Louvain, Belgium where Barnes attended the University of Louvain

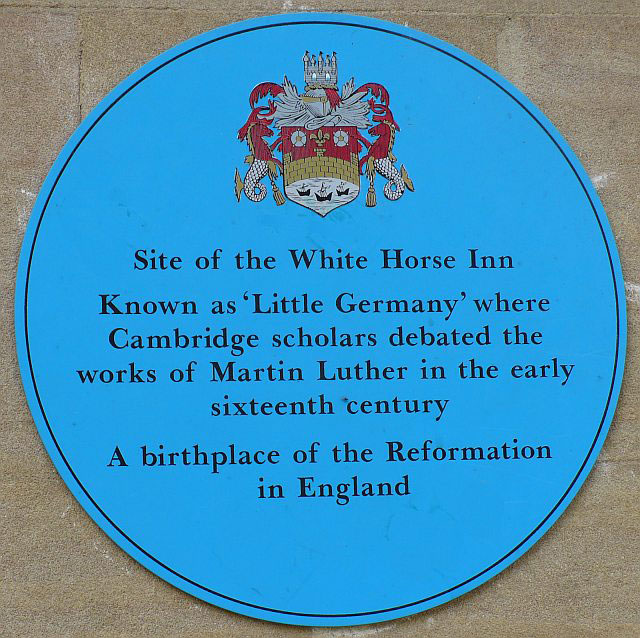

As Austin prior at Cambridge, Barnes introduced the ancient Latin writings of Cicero and others, then moved on to the Pauline Epistles of the New Testament. As Foxes’s Book of Martyrs claims, “he became mighty in the Scriptures over against bishops and hypocrites.” One of the early converts from Barnes’s exposition was Thomas Bilney, who went even further and embraced Protestant theological principles. Bilney’s powerful evangelical preaching convinced both Barnes and the Archbishop of Canterbury, Hugh Latimer, to adopt “Lutheran” doctrine. Barnes, Bilney and Latimer became the nucleus of an evangelical discussion group, known by their colleagues as the “Cambridge Germans,” which met as early as 1518 at the White Horse Inn in Cambridge, discussing Luther’s various critiques of Roman Catholic doctrine. A number of the young humanists became bishops. They were critics of church, state, and university and their leader was Robert Barnes. In 1520, the Church proscribed Luther’s writings, yet the White Horse group continued to meet and discuss, even to their peril.

A placard marks the location where the White Horse Inn once stood, before being demolished in 1870 to make room for the construction of the

King’s College Scott’s Building

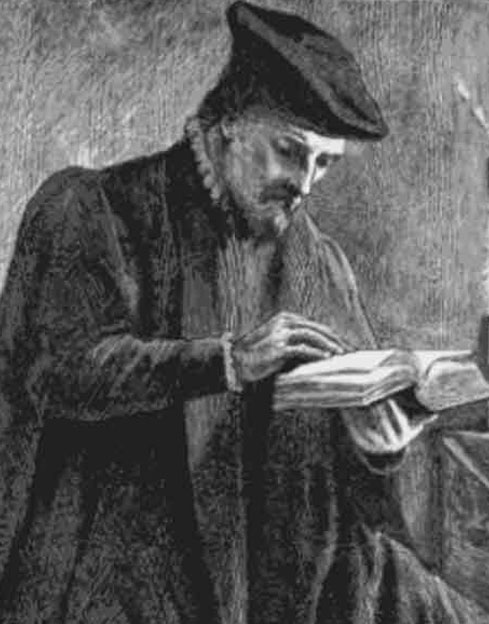

Thomas Bilney (c. 1495-1531)

Hugh Latimer (c. 1487-1555)

Barnes had not yet publicly preached anything that could be indisputably deemed heretical, but the priests had nonetheless been sensitive to his criticisms of their superstition. Barnes was “utterly tactless” when it came to denouncing Church or clerical abuses, and finally stepped on too many toes when he attacked the glittering wealth of the Church compared to the poverty of Christ (in a Christmas sermon), and also proclaimed that Christians should not sue other Christians. The Priory pulpit was a good sounding board for reform since the Austin friars were not subsidized by the state. Nonetheless, Barnes was hauled before Cardinal Wolsey in 1525 to answer for his apparent heresies.

The interior of St Edward King and Martyr Church in Cambridge, England where Barnes gave his infamous Christmas sermon, and where Latimer regularly preached from the pulpit visible in the back left

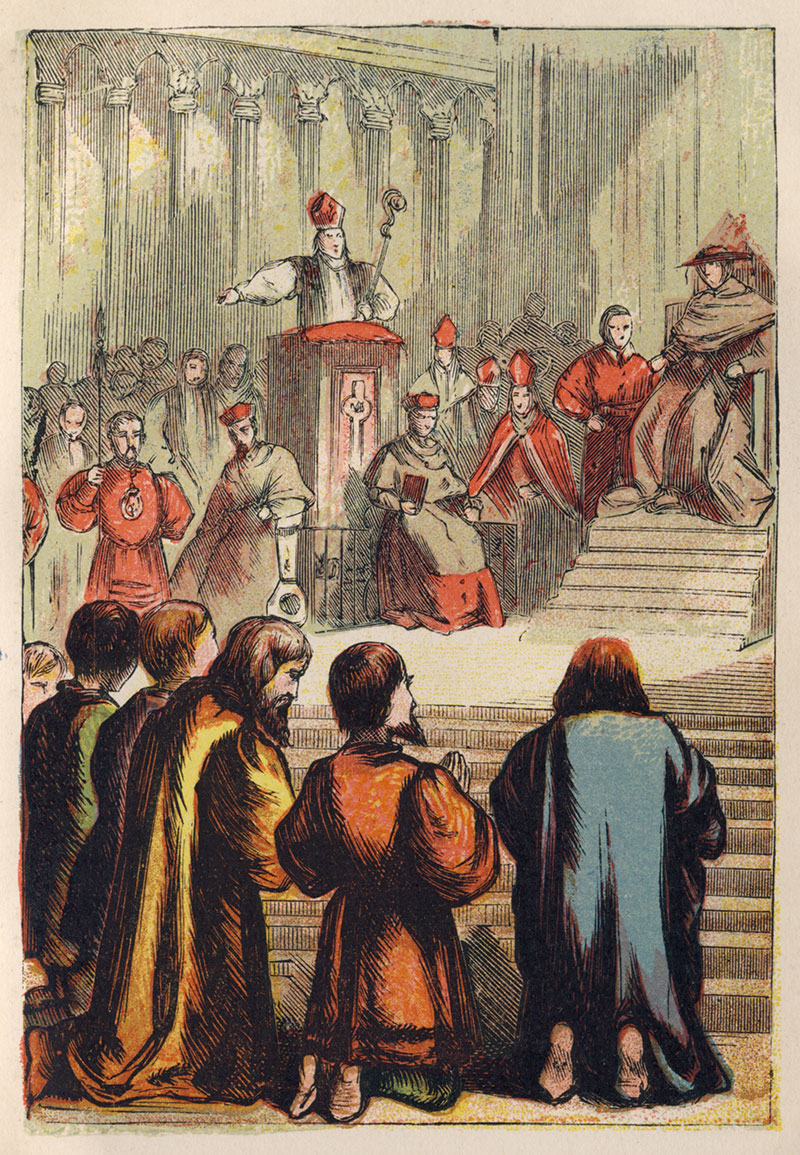

Barnes appearing before Cardinal Wolsey, from an 1870 illustration in J.H. Merle d’Aubigné’s History of the Great Reformation in Europe in the Times of Luther and Calvin

His lack of penitence or humility at the hearing was an affront to the Cardinal, but Barnes had his supporters among the Cardinal’s retinue, as well as the students of the University. Barnes was persuaded by his friends to recant to save his life. While it worked to spare him for the time being, while later incarcerated (1529), he was caught selling Tyndale’s New Testaments from prison, smuggled in from the continent, to Lollards. The Church dropped him from the Austin priory and remanded him to Fleet prison to be burned at the stake. Robert Barnes escaped one night, and after writing a suicide note piled his clothes up by the river. As the authorities dragged the river for his body, he sailed to the continent fully clothed and turned up at Wittenberg in Germany, where he became a close friend of both Luther and Melanchthon.

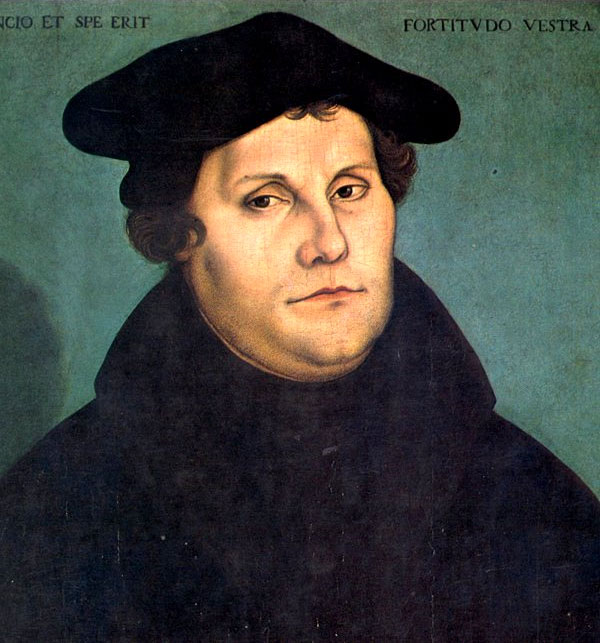

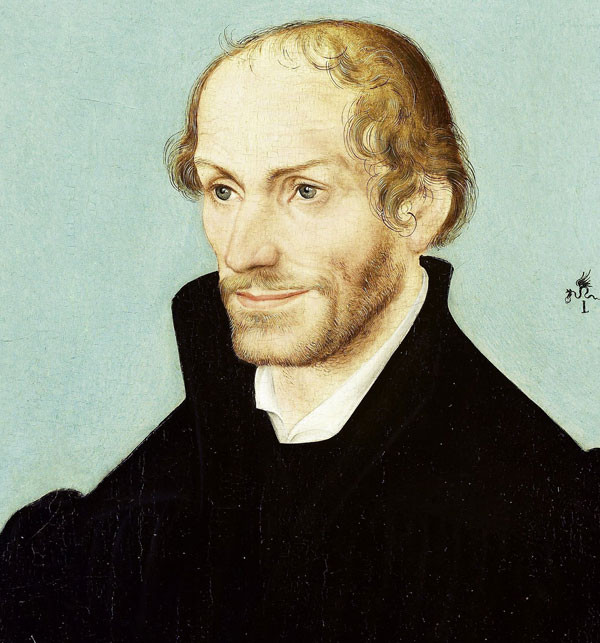

Martin Luther (1483-1546)

Philip Melanchthon (1497-1560)

While at Wittenberg, Barnes wrote the first Protestant history of the papacy. He also became the most thorough evangelical of the White Horse group, some of whom followed Erasmus and remained in the Church while others followed Luther and became decided Protestants. The exchange between Luther and Erasmus on the nature of the human will became the decisive theological point of division. Luther later published their debate as On the Bondage of the Will, a work still in print and a powerful biblical argument against the Roman Catholic “free will doctrine.”

The Lutherhaus (known as The Black Cloister in Luther’s day) in Wittenberg, Germany was originally part of the University of Wittenberg, but became the renowned home of Martin Luther and therefore a hub of the Reformation

Barnes produced many theological tracts and books in English vernacular, which were subsequently smuggled into England and widely distributed, especially to students and scholars. King Henry VIII attempted to crack down on the Protestant heresies while he himself promoted his own version of Catholicism against the papacy. Wherever Barnes went he favorably impressed the theologians and the princes of Europe. No one could ignore the brusk and uncompromising English don and his powerful witness for Christ.

In 1530, King Henry was embroiled in a theological disputation with the Pope over the subject of divorce and sought theological support for his position all over Europe, even among Lutherans, about whom he had been dangerously critical in the past. Robert Barnes wrote a book on the issue, siding with the King’s position against the English bishops. Henry’s representative in Europe carried the book, along with Barnes’s confession of loyalty to the crown (and Tyndale’s translation of I John). The oft-divorced English monarch invited Barnes to return to England, all was forgiven, and Barnes continued writing with the King’s favor. For nine years, Barnes preached the Gospel and wrote works assisting the King in his war with the Pope. The Lord Chancellor Thomas More hated Barnes and considered him an arch-heretic, always scheming to get rid of the dangerous man.

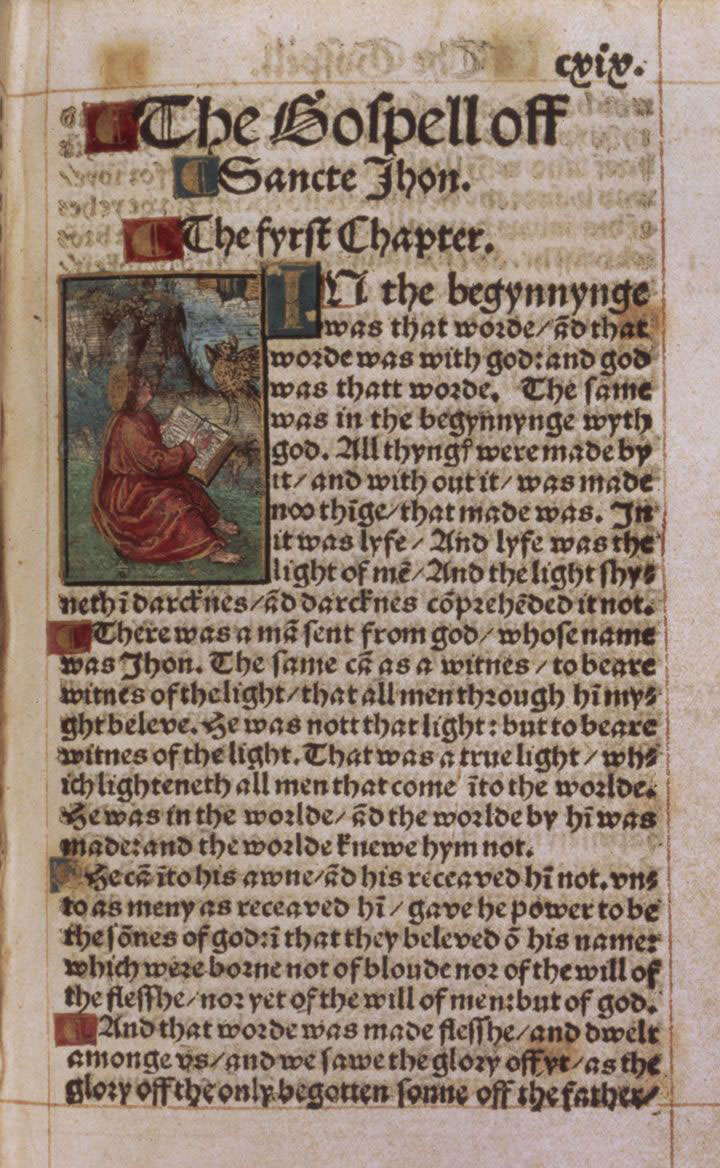

The beginning of the Gospel of John from a copy of the 1526 edition of William Tyndale’s New Testament, at the British Library

King Henry VIII of England (1491-1547)

Sir Thomas More (1478-1535)

The Cambridge scholar returned to the continent as a representative of Henry VIII, and even pastored an English Lutheran congregation in Germany for a while. Seeking diplomatic alliances with many Protestant princes, Barnes represented the King throughout the 1530s, with uneven results. Without theological compatibility, however, the Lutherans would not join Henry in political alliance. The King remained wedded to Catholic doctrine, but to his wives, not so much.

“Barnes and His Fellow-Prisoners Seeking Forgiveness”, from an 1887 copy of Foxe’s Book of Martyrs

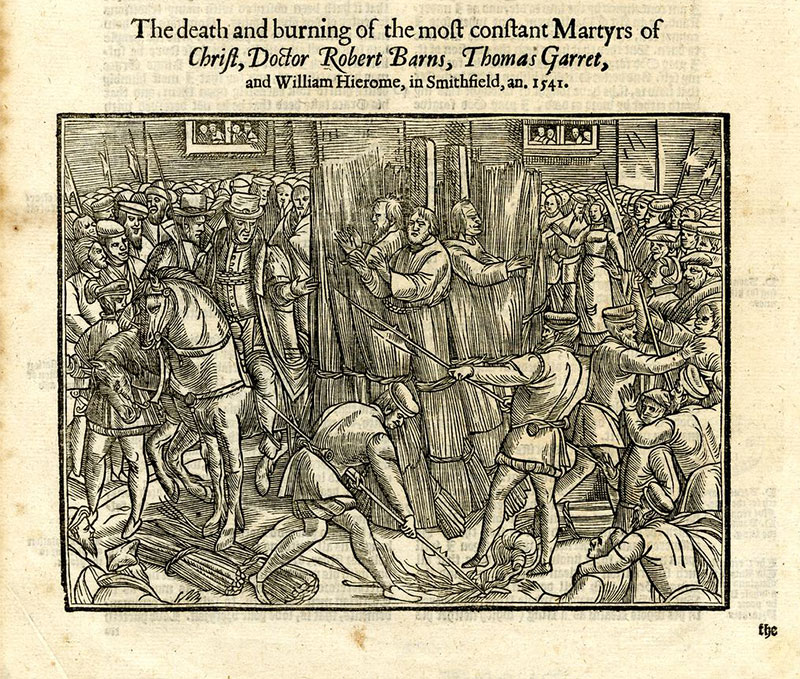

In 1539 Barnes returned to an England in which the strong Catholic party, especially bishops, were in the ascendency. It was a dangerous environment which Barnes should have avoided, but, “he had all the impulsive excitement which throws discretion overboard, and memory was seldom to prevent him from making the same mistake twice.” His public criticism of the bishops and continued evangelistic preaching from the pulpit made him a marked man. His supporters at court could not save him, and some of them, in fact, went down with him, and Robert Barnes, with the King’s approval, was burned at the stake as a heretic July 30, 1540. Luther called him Saint Robert and Henry VIII an “incarnate devil.” The loyal heretic who had outlived his usefulness had nonetheless won many to Christ and helped pull down the stronghold of Satan which had held England in thrall for centuries.

An illustration from a 16th century edition of Foxes’s Book of Martyrs, with the inscription: “The death and burning of the most constant Martyrs of Christ, Doctor Robert Barns, Thomas Garret, and William Hierome [Jerome], in Smithfield, an. 1541.”

For further study, read Luther’s English Connection by James Edward McGoldrick (1979).

Image Credits: 1 Louvain (Wikipedia.org) 2 White Horse Inn (Wikipedia.org) 3 Thomas Bilney (Wikipedia.org) 4 Hugh Latimer (Wikipedia.org) 5 St Edward King and Martyr Chapel (Wikipedia.org) 6 Barnes & Wolsey (Wikipedia.org) 7 Martin Luther (Wikipedia.org) 8 Philip Melancthon (Wikipedia.org) 9 Lutherhaus (Wikipedia.org) 10 Tyndale Bible (Wikipedia.org) 11 King Henry VIII (Wikipedia.org) 12 Thomas More (Wikipedia.org) 13 Barnes & Fellow Prisoners (Wikipedia.org) 14 Barnes & Fellow Prisoners’ Execution (Wikipedia.org)