“For I know the plans I have for you,” declares the LORD, “plans to prosper you and not to harm you, plans to give you hope and a future.” —Jeremiah 29:11

Decree Expelling Jews from Spain Goes into Effect, August 2, 1492

![]() n 1492 Columbus sailed the ocean blue,” we learned in our earliest days in school. Leaving aside that the little rhyme to get children to remember the year Columbus “discovered America,” the doggerel now triggers the sensitive but ignorant imbeciles that consider “Admiral of the Ocean Sea,” Christopher Columbus, as the white supremacist perpetrator of a holocaust in the New World. It just so happens that another event, perhaps more important than the exploration of C. Columbus, took place the same year in the same country: the expulsion of the substantial Jewish population of Spain. The action created another Jewish diaspora that changed history.

n 1492 Columbus sailed the ocean blue,” we learned in our earliest days in school. Leaving aside that the little rhyme to get children to remember the year Columbus “discovered America,” the doggerel now triggers the sensitive but ignorant imbeciles that consider “Admiral of the Ocean Sea,” Christopher Columbus, as the white supremacist perpetrator of a holocaust in the New World. It just so happens that another event, perhaps more important than the exploration of C. Columbus, took place the same year in the same country: the expulsion of the substantial Jewish population of Spain. The action created another Jewish diaspora that changed history.

The Grand Inquisitor Tomás de Torquemada offers to the Catholic Monarchs, Ferdinand and Isabella, the Edict of Expulsion of the Jews from Spain for their signatures, 1492

After the fall of the Roman Empire, Hispania (the Iberian Peninsula) was conquered by the Teutonic tribe known as the Visigoths, around A.D. 476. They adopted a form of Christianity and held political sway until they were in turn overrun by the Islamic Empire in North Africa in 711, who took advantage of the political unrest and divisions of the Spanish kingdom. The Muslims failed to conquer the Basques and held Galicia, the extreme northwest, for only twenty-eight years. The City of Granada, however, became an Islamic stronghold for 781 years. Throughout the Islamic Caliphate, Jews and Christians paid tributes and taxes to their Muslim overlords, and were, in turn, allowed to practice their faith.

The last Muslim king of Granada, Abu Abdullah Muhammad XII, hands over Granada, the last stronghold of Muslims in Andalusia, to the Catholic Monarchs Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile

In the 12th and 13th Centuries the Roman Church countenanced within its pale certain anti-Jewish movements, passing laws restricting rights and looking the other way when persecutions arose. The 14th Century brought wars and the bubonic plague, spelling the end of relative tolerance of Jews by the Catholic Church. In the Kingdom of Navarre in 1321, Jews were massacred in two towns when the “Shepherd’s Crusade” crossed the Alps into Spain. In the 1340s, Jews were blamed for the Black Death, and were massacred in Barcelona and Catalonia. On several other occasions in the century, synagogues were burned and Jews cut down in other cities in Spain, sometimes as a result of “political and economic unrest” sometimes as scapegoats for diseases or other social disruptions. The Talmud was outlawed, Jews were forced to attend Mass. Required conversions and baptisms characterized persecution in Castile and Aragon in the early 1400s. Throughout the century, “conversos” were looked upon with suspicion, since their conversions were coerced.

‘At the Feet of the Savior’ depicts a massacre of Jews in Toledo, Spain—one of many similar massacres during the Middle Ages

The Kingdoms of Aragon and Castile combined their political dominance with the marriage of teenage cousins Ferdinand and Isabella in 1469. Some Jews who were baptized as Christians, the conversos, continued to worship God in their old way secretly, others moved to the countryside to avoid the crack-downs in the cities. In the Court of Castile, Jews held prominent administrative and financial positions. The Queen protected her Hebrew subjects and their worship was permitted, but such was the not the case in most Spanish states. In 1478 the Pope assigned members of the “Holy Inquisition” to Spain to investigate and prosecute converts who reverted to Judaism or attempted to worship in secret. In twelve years, the Inquisition condemned 13,000 for the secret practice of Judaism. One historian claims the Inquisition burned 32,000 heretics to death in Spain. Ferdinand and Isabella still continued to try and protect the Jews of their kingdoms, until 1492. They tried to isolate the Jews in ghettos to better avoid persecution, but enforcement of both protective measures and restrictions were ineffective.

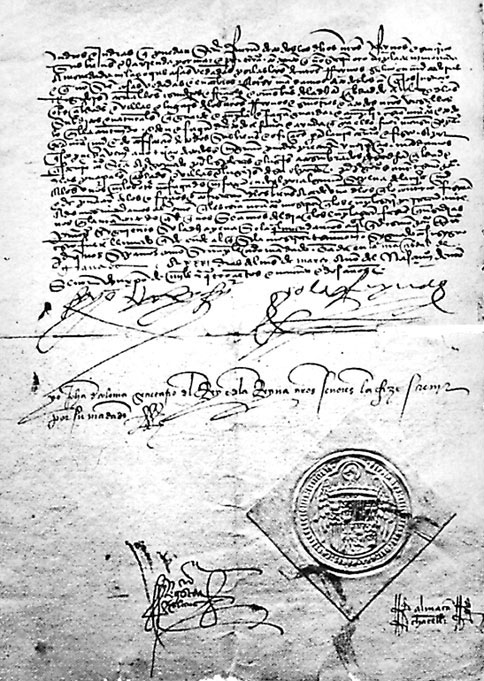

A sealed copy of the Edict of Granada (also known as the Alhambra Decree, or Edict of Expulsion), was issued in 1492

After the final expulsion of the Muslims in the War against Grenada in 1492, Ferdinand and Isabella signed the decree of expulsion of the Jews of Grenada, to go into effect on August 2, 1492. The Inquisitor General Thomas de Torquemada played a key role in the royal decree. The Jews were not allowed to take gold or silver, horses or arms with them, or ever return to Spain. Christians who helped Jews hide or violate other rules would be subject to the loss of all their property also. The opportunity to abandon their faith and become Catholics was still offered as an option, and the preaching of “the holy Gospel and the doctrines of holy Mother Church” went forth across Spain. Perhaps half the Jews chose to convert, including many rabbis.

Tomás de Torquemada (1420-1498), Grand Inquisitor of the Spanish Inquisition

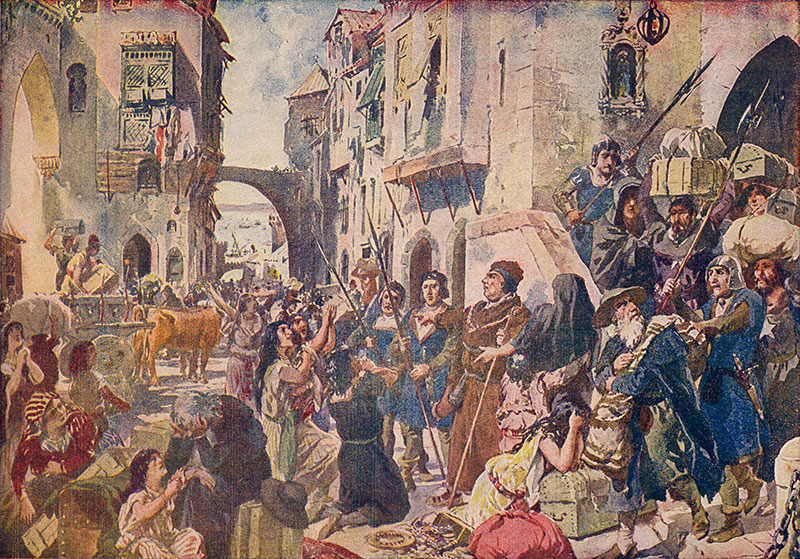

Expulsion of the Jews from Portugal, 1497

No one actually knows how many Jews left Spain. Estimates range from 40,000 to 800,000. They would ever be known as Sephardic Jews. Technically, there were none left in Spain, but it is well known that many went underground with their religion there and the search for them continued for another century. Many of the diaspora of Spain settled in Portugal, from where they were expelled four years later into Italy, North Africa, Navarre, the Balkans, Holland, and the Middle East. Historians have noted that the expulsion of the Jews of Spain took place in the same month as the destruction of the Temple and exile to Babylon and the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem in 70 A.D.

A Jewish festival in Tetouan, Morocco

Over time, the Sephardic Jews assimilated in the countries they arrived in. Among them were successful traders, authors, economists, philosophers, businesspeople, famous architects, and wise and resourceful rabbis. Among the descendants of the Sephardic diaspora of Spain and Portugal are the philosophers Spinoza and Karl Marx, British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli, French writer Montaigne, American super-lawyer Alan Dershowitz, humorist Jerry Seinfeld, and many others of note. Like the exiled Huguenots of France, what persecutors intended for evil, God had other unknown powerful providential plans.