“So God created man in His own image; in the image of God He created him; male and female He created them.” —Genesis 1:27

The Erie Canal Completed, October 26, 1825

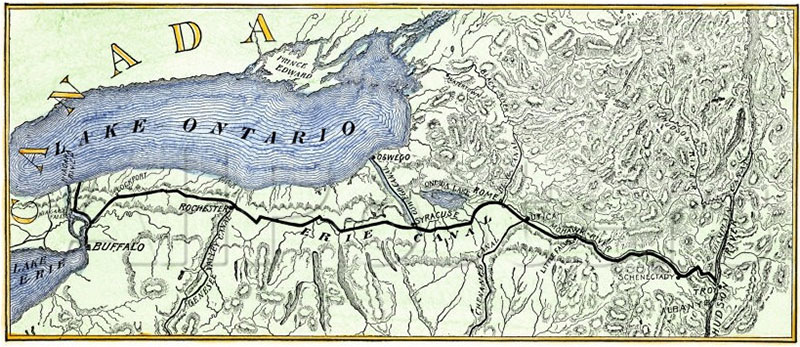

![]() he Appalachian Mountain range extends more than 1,500 miles north and south, and up to four hundred miles inland from the Atlantic coast. The only cut-across, north of Alabama, is the Hudson River/Mohawk River Valleys in upstate New York, which separate the Adirondacks and Catskills. As early as the eighteenth century, traders and engineers proposed building a canal that would follow the Mohawk Valley into the Hudson River. The New York Legislature authorized and funded a survey which launched on the July 4, 1808. Construction began ten years later and was completed on October 26, 1825. The Erie Canal became the second longest man-made canal in the world, and made New York City the most important and wealthiest city in the United States. The effects of that engineering feat affected the entire country and transformed the social and commercial enterprises, even after it became secondary to the railroads.

he Appalachian Mountain range extends more than 1,500 miles north and south, and up to four hundred miles inland from the Atlantic coast. The only cut-across, north of Alabama, is the Hudson River/Mohawk River Valleys in upstate New York, which separate the Adirondacks and Catskills. As early as the eighteenth century, traders and engineers proposed building a canal that would follow the Mohawk Valley into the Hudson River. The New York Legislature authorized and funded a survey which launched on the July 4, 1808. Construction began ten years later and was completed on October 26, 1825. The Erie Canal became the second longest man-made canal in the world, and made New York City the most important and wealthiest city in the United States. The effects of that engineering feat affected the entire country and transformed the social and commercial enterprises, even after it became secondary to the railroads.

An 1840 map showing the route of the Erie Canal from Lake Erie in Buffalo cutting east to the Hudson River in New York City

As Americans moved westward and the Ohio Valley, Great Lakes region and Midwest became more and more productive of agricultural products, the need to transport those grains and produce to the coast and to the world increased with every passing year. The Great Lakes Region promised great wealth to those who could transport to coastal and ocean traffic the fastest. Shipping down the Mississippi already boosted New Orleans as the largest city in the South, and prosperous to a high degree.

The bustling, prosperous port of New Orleans on the Mississippi River in the 1840s

In 1800 it still took about four weeks to travel from New York City to Detroit, Michigan. The roads, such as they were, made passengers and freight crawl at the pace of oxen. A navigable canal through the Mohawk Valley presented some difficult problems, like a rise of six hundred feet in elevation and limestone barriers left in the wake of the ice age. Since there were no civil engineers in the United States at the time, amateur surveyors and other sorts of engineers would design and build the Erie Canal, and do so with trial and error, innovation and creativity.

An 1832 graph showing the rise in elevation needed along the route of the Erie Canal

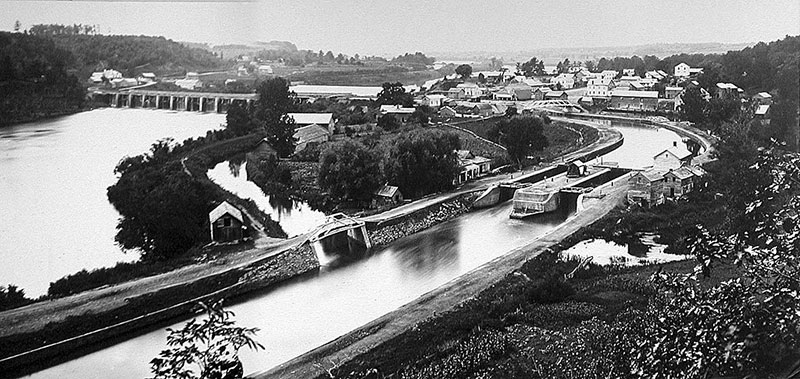

Since most of the work required men with shovels, more than five thousand immigrants, mostly Irish and German, came to America to work on the canal. Nativists resisted and resented the newcomers, primarily for their Roman Catholicism. The violence was not widespread and the canal proceeded steadily toward its terminus at both ends—Albany, the capitol on the Hudson, and Buffalo, the up-and-coming city on Lake Erie—about 360 miles apart. Rochester, Syracuse, and Tonawanda would become watershed cities along the route, along with smaller towns which served as loci for the thirty-four locks that raised the canal over the Niagara Escarpment. In the end, the channel would cut forty feet wide and four feet deep, later expanded and modified to be both wider and deeper.

A portion of the canal today—Gateway Harbor along the Erie Canal in North Tonawanda, NY—near its connection to the Niagara River

Governor DeWitt Clinton backed the project with all his political skills, and faced ridicule and resistance for his efforts. Known as “Clinton’s folly,” and “Clinton’s ditch”, opponents cited the great cost of the project and the likelihood of failure, as well as the importation of poor immigrants and their negative influence and high mortality along the routes. The Holland Land Company was selling thousands of acres in western New York, and their agent, Joseph Ellicott, viewed the canal as a boon to land speculators and real estate sales, so fully supported the Governor and the canal, a powerful ally.

DeWitt Clinton (1769-1828), governor of New York and enthusiastic proponent of the Erie Canal project

Old Erie Canal State Historic Park, at Cedar Bay Park, DeWitt, NY

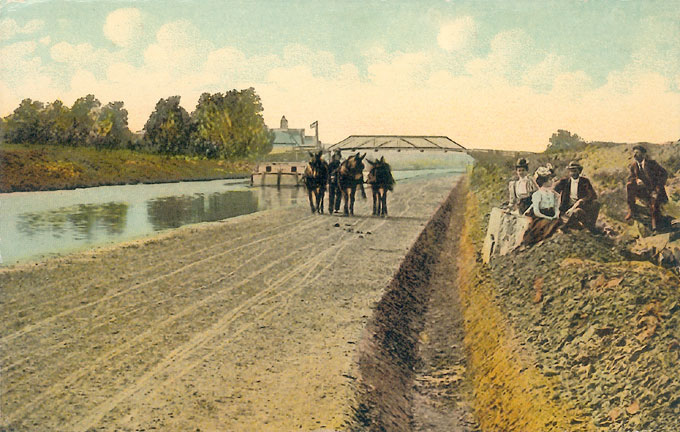

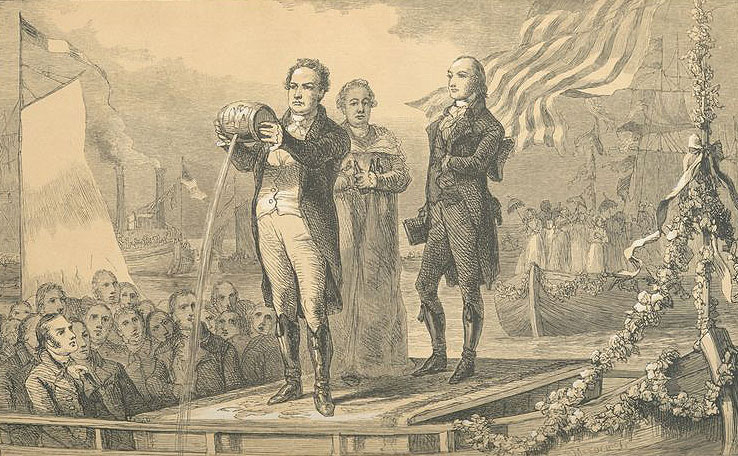

The canal, upon completion, cut shipping costs by 95% and promoted a population boom into western New York and points westward. The engineers used the displaced soil to create the towpath for the horses and mules to walk, to which the canal boats were attached. For most people moving westward on freight boats, sleeping accommodations were made atop the trade goods or personal possessions. Packet boats designed for passengers sometimes included dining rooms, carpeted floors, and reading rooms, as well as pull-down beds and bunks. Captains occasionally hired entertainers as well. Completed in eight years, Governor Clinton carried water from Lake Erie to the Hudson River along the length of the canal to New York City, dumping it in New York Harbor as a symbol of the completion of the great engineering enterprise.

The canal and tow path still in use in 1905

Governor DeWitt Clinton pouring water from Lake Erie into the Hudson River during a ceremony to mark the completion of the canal, and the consequential joining of these two bodies of water

Maintenance of the canal required the use of “underwater cement” to plug leaks. Speed limits were used to slow erosion. They built feeder canals connecting the system to the Finger Lakes and Lake Champlain, and the Erie itself was expanded several times, well into the 20th century. Tolls along the canal paid for its construction in the first year of operation, and the wealth it brought to New York City and Buffalo transformed their economies and influence. Famous authors wrote about the canal. Today, pleasure craft make up most of the traffic on the canal system, but as late as 2012, more than 40,000 tons of cargo still moved along the canal system.

The keg from which Governor Clinton poured the water of Lake Erie into the Hudson River on October 26, 1825

An artist’s 1855 rendition of the Erie Canal at Lockport, NY

Man is created in God’s image, and technology and creativity providentially reflect what has always been true of man as an analog of the Creator Himself. The Erie Canal today wanders through a beautiful countryside where the commercial value has declined, yet it offers a slow-paced reflection on the creation through which it flows.

A stone aqueduct of the Erie Canal crosses the Mohawk River in Rexford, NY

Image Credits: 1 Canal Route (Wikipedia.org) 2 New Orleans (Wikipedia.org) 3 Elevation (Wikipedia.org) 4 Tonawanda (Wikipedia.org) 5 DeWitt Clinton (Wikipedia.org) 6 Old Erie Canal State Park (Wikipedia.org) 7 Mules Towing (Wikipedia.org) 8 Completion Ceremony (Wikipedia.org) 9 Water Keg (Wikipedia.org) 10 Lockport, NY (Wikipedia.org) 11 Rexford, NY (Wikipedia.org)