The Inauguration of John Tyler, April 6, 1841

“My son, observe the commandment of your father.” —Proverbs 6:20a

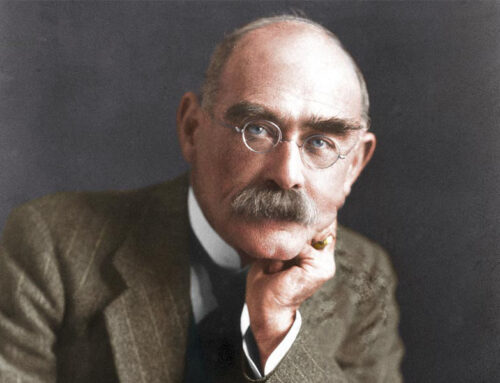

![]() resident Truman said of him, “he is one of the Presidents we could do without.” Theodore Roosevelt suggested that “he has been called a mediocre man; but this is unwarranted flattery.” The New York Times obituary stated that “he had left the Presidency as the most unpopular public man that had ever held any public office in the United States.” But then, none of them cared a whit for the meaning of the Constitution or dared oppose their own party when that party passed unconstitutional legislation. John Tyler stood his ground on principles, an almost unheard of position in the twentieth or twenty-first centuries—presidents actually having sound convictions or standing by them.

resident Truman said of him, “he is one of the Presidents we could do without.” Theodore Roosevelt suggested that “he has been called a mediocre man; but this is unwarranted flattery.” The New York Times obituary stated that “he had left the Presidency as the most unpopular public man that had ever held any public office in the United States.” But then, none of them cared a whit for the meaning of the Constitution or dared oppose their own party when that party passed unconstitutional legislation. John Tyler stood his ground on principles, an almost unheard of position in the twentieth or twenty-first centuries—presidents actually having sound convictions or standing by them.

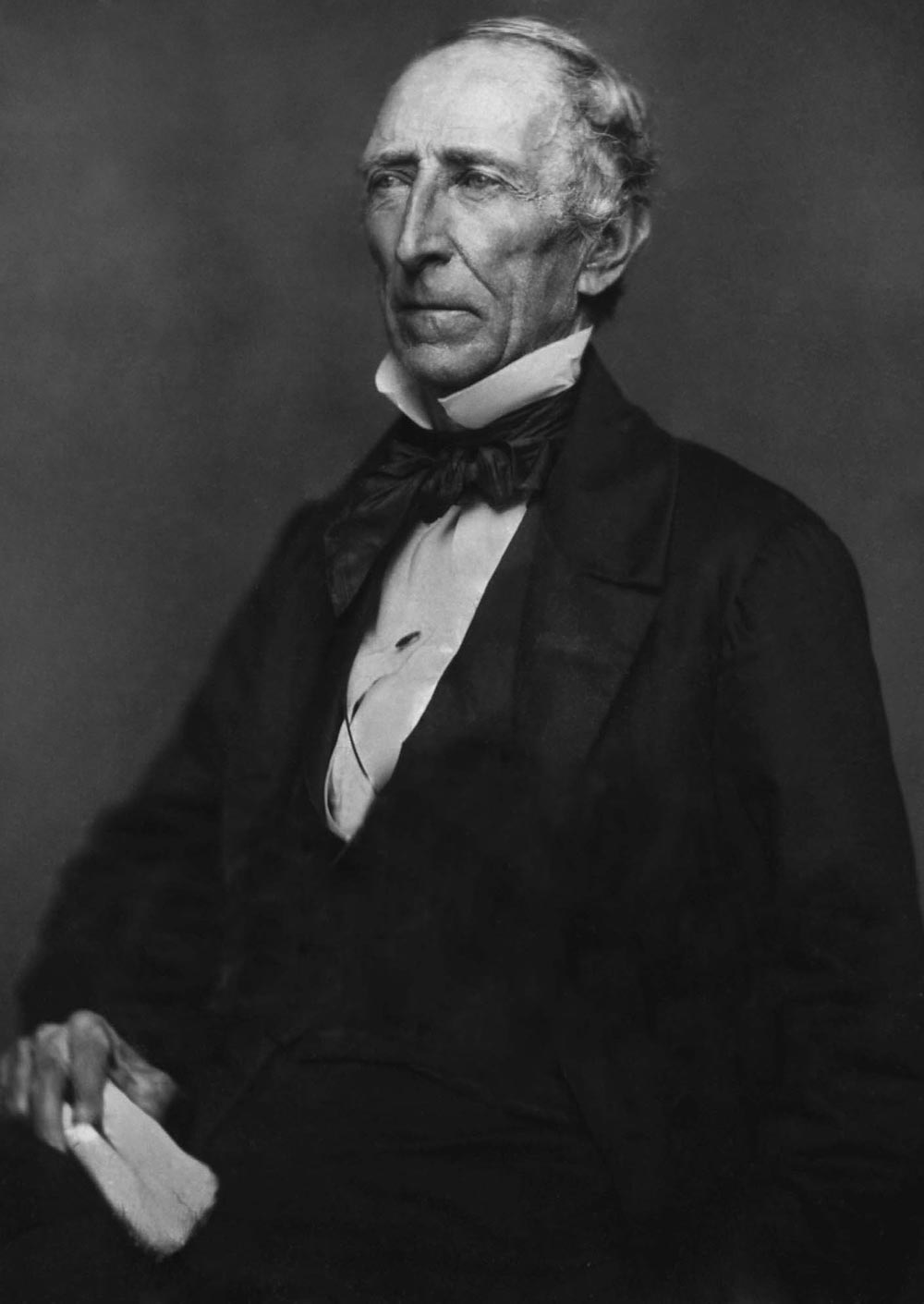

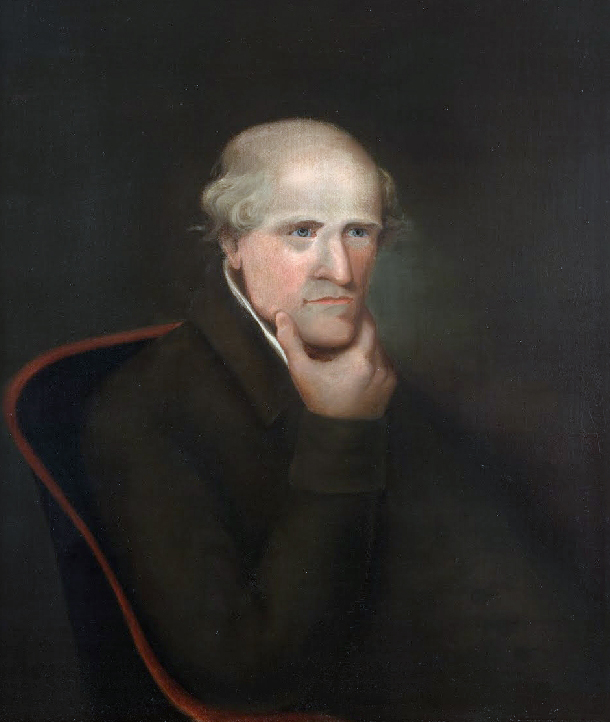

John Tyler (1790-1862)

John Tyler (1790-1862) was the son of John Tyler, Sr., known as “Judge Tyler.” Raised in rural Charles City County Virginia, both Tylers were graduates of the College of William and Mary. Judge Tyler’s roommate was Thomas Jefferson. The Senior Tyler self-consciously trained his son to take his place in the seats of power, and regaled him with stories of the Founding Fathers and their sacrifices for the Republic. Young John graduated at the age of 17, passed the bar at 19 and opened a law practice, while his father served as governor of Virginia. Encouraged by his father to go into politics, John Tyler was elected to the House of Burgesses at the age of 21. There he made known his strong allegiance to States Rights and the Constitution, as had his father before him. In 1816, he was sent to Congress representing his Charles City County constituents.

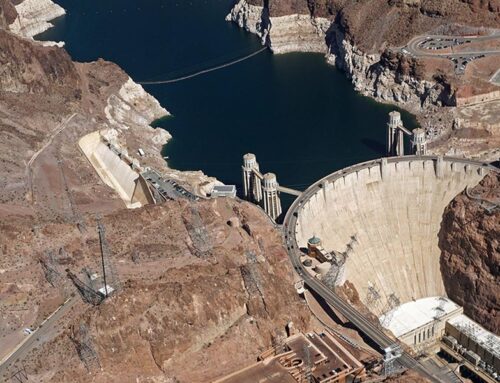

John “Judge” Tyler, Sr. (1747-1813) father of U.S. President John Tyler

Greenway Plantation in Charles City County Virginia, birthplace of John Tyler

Having married in 1813, with a growing family (which eventually reached fifteen children), and citing poor health, Tyler stepped down from Congress to build up his law practice. Upon his return to state politics, John was appointed Governor, but within a year entered the United States Senate by legislative acclimation. As a senator Tyler became known as a strong “Jeffersonian,” always opposing the centralization of power and defending Constitutional State authority. His independent thinking and actions sometimes led to opposing his own party, eventually breaking with the President and leader of it, Andrew Jackson.

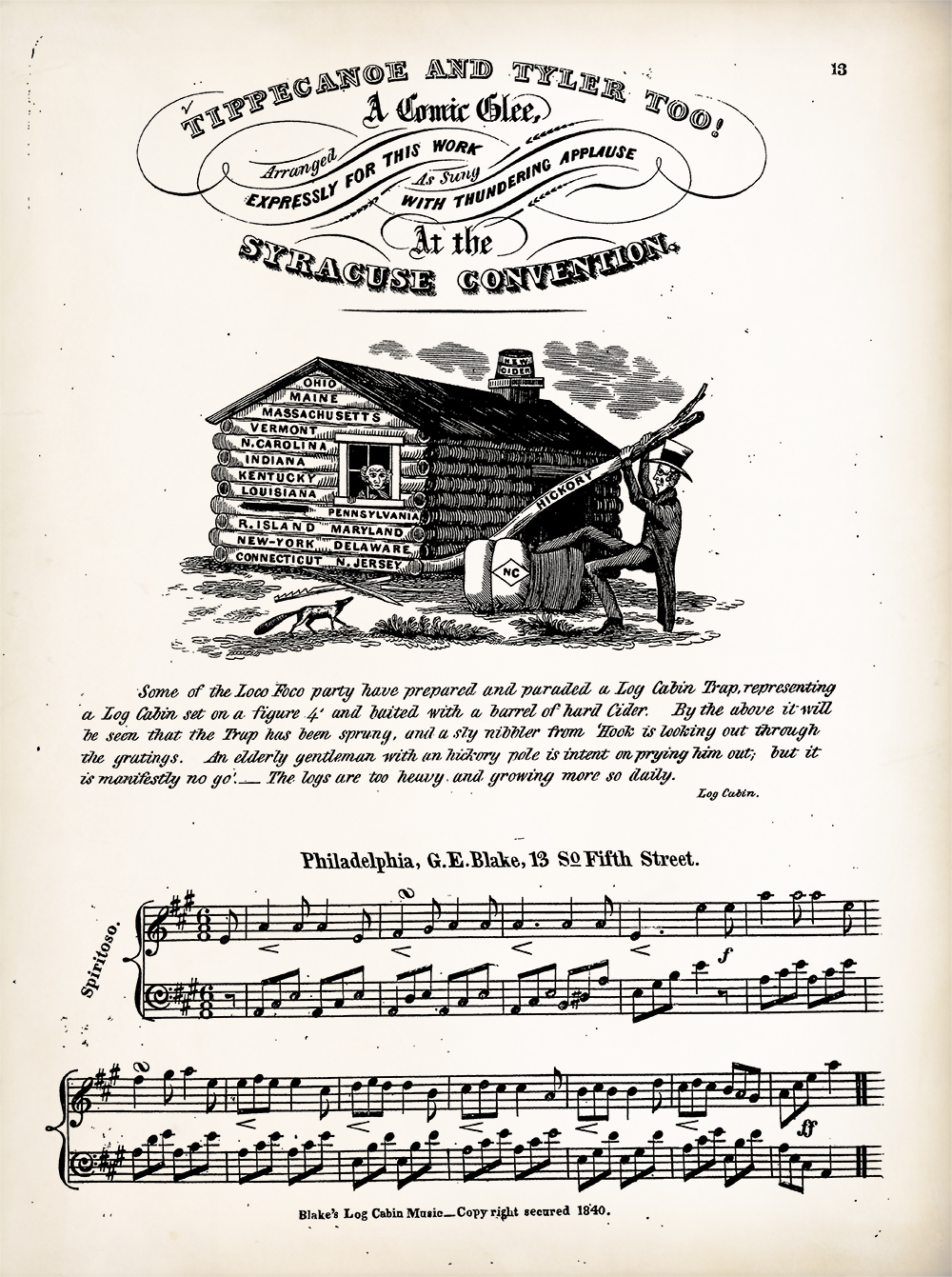

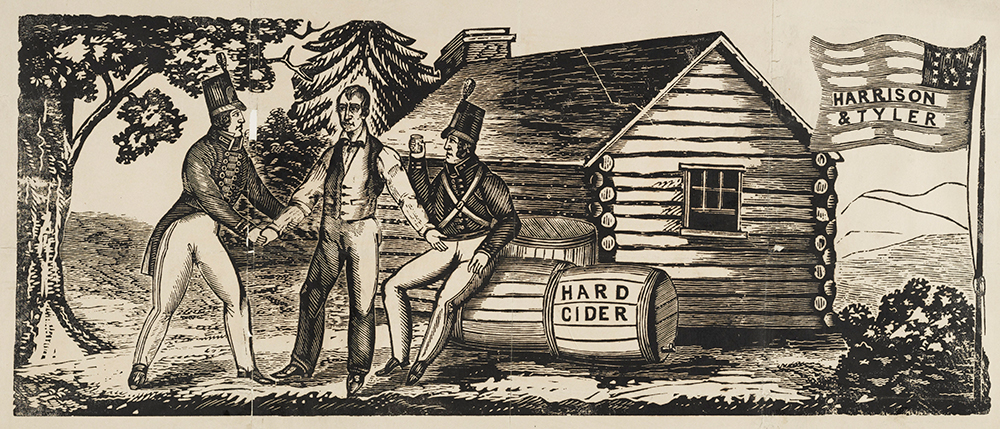

Tyler supported the right of South Carolina to nullify unconstitutional Federal legislation and opposed Jackson’s dismantling of the National Bank by fiat. Thus identifying with the up-and-coming anti-Jackson Whig Party, Tyler resigned from the Senate when he realized Virginia’s House of Delegates was going to ask him to vote against his conscience and political convictions. Leaving the Senate, Tyler returned to state politics as a member of the Virginia House. In a remarkable turn of events, the Virginian’s sterling character and popularity in his home state caused the Whig Party to add Tyler to the ticket as Vice Presidential candidate in the election of 1840, along with popular General William Henry Harrison for President. They won the “Hard Cider and Log Cabin” election and the slogan “Tippecanoe and Tyler Too” passed into history as a most successful campaign.

Score to “Tippecanoe and Tyler Too”, a popular and influential tune of the Whig Party’s Log Cabin Campaign, 1840

Harrison and Tyler’s “Hard Cider and Log Cabin” campaign emblem, 1840

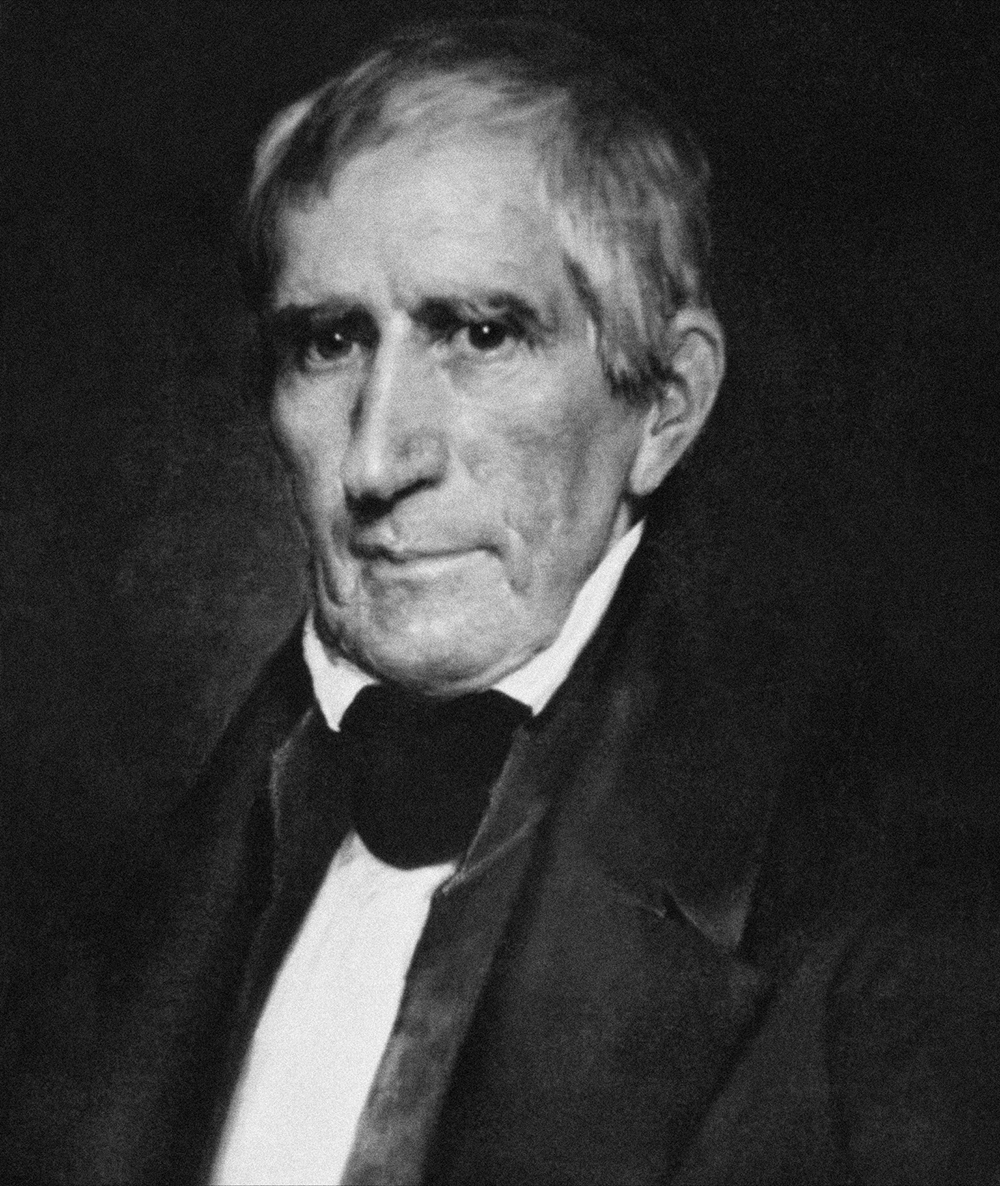

Tyler returned to his home in Williamsburg, Virginia to tend to his family while Henry Clay, the leader of the Whig Party, pulled strings and manipulated the President to his heart’s content. And then President Harrison died. John Tyler is often only known at the President of Firsts. The fifty-one-year-old President became the first Vice-President to accede to the Presidency upon the death of the incumbent, as well as the youngest up to that time. Racing to Washington and taking the oath as the successor, Tyler set a precedent that has been followed ever since. He delivered an inaugural address reasserting his States’ Rights principles and “Jeffersonian philosophy.” He would soon discover that the Whig Party and he were very incompatible.

9th U.S. President William Henry Harrison (1773-1841) served only 31 days in office

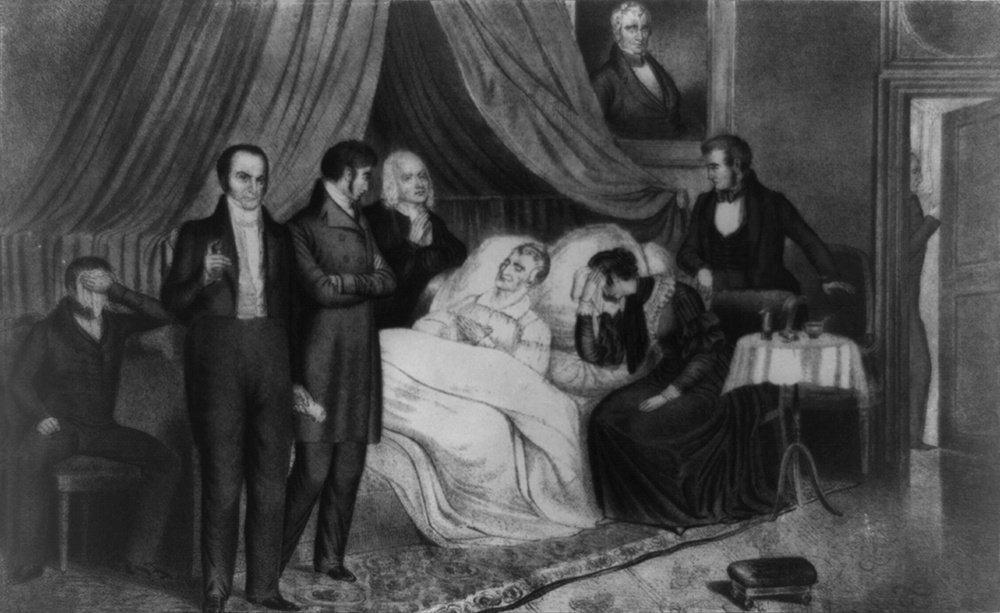

The death of William Henry Harrison, April 4, 1841

The rest of his Presidency (which wags ever since have called “His Accidentcy”), was one of opposing the legislation of his own party which controlled Congress, because of the unconstitutional nature of much of their legislation. His inherited cabinet resigned (except for Daniel Webster), and the first impeachment proceedings were started against him. As a man without a party, Tyler persevered through his term as tenth President, suffering the attacks and resistance of both Whigs (future Republican Party) and Democrats (his former colleagues). His wife was the first spouse to die; he remarried in the White House, a first.

Letitia Tyler (1790-1842), Tyler’s first wife, died the year after his inauguration

Julia Tyler (1820-1889) Tyler’s second wife, whom he married while in office

John Tyler’s foreign policy initiatives were successful, however, since he had control of that aspect of Presidential power and duty, including bringing Texas into the Union. He left the office a pariah but with his honor and convictions intact, and retired to Sherwood Forest, his home in Charles City County, Virginia. His grandson lives there still. President Tyler died in 1862, beloved by his home state and all the South, the only President not a citizen of the United States at the time of his death—a Confederate congressman. It was he to whom the South turned to seek reconciliation in the early days of secession, but his commission was rebuffed by the Lincoln administration, and the war was on.

Sherwood Forest Plantation, Tyler’s home for the final twenty years of his life

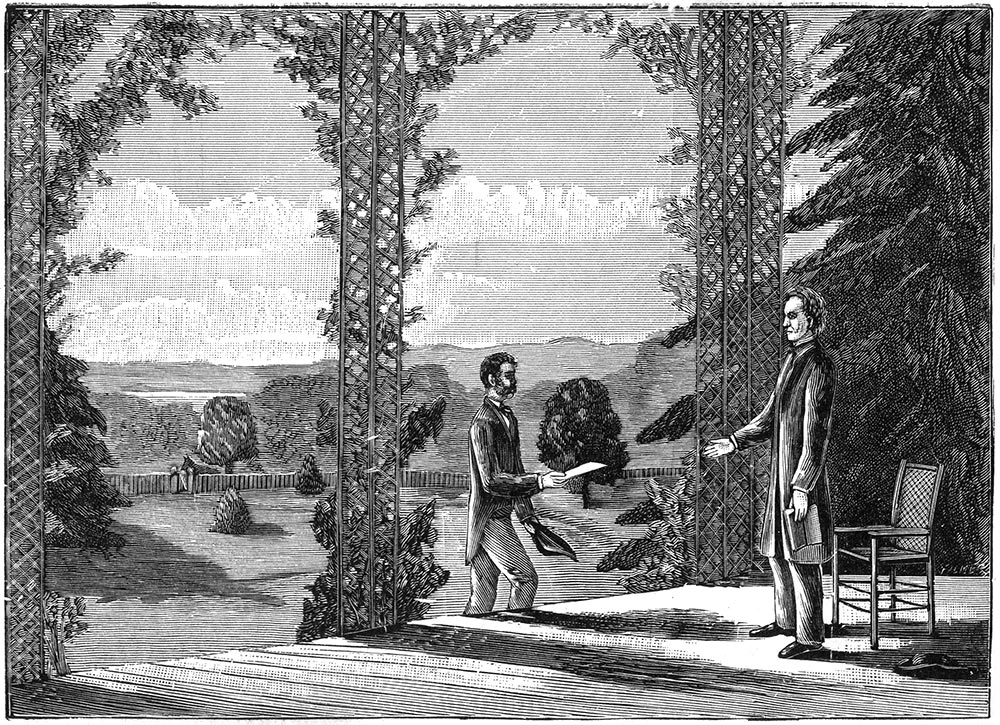

A messenger deliver news to Vice President John Tyler of President Harrison’s death

The man who had been groomed by his father for greatness is hated and vilified by most modern historians. Flawed men who, however, retain their honor and principles, will always run afoul of those who have set themselves up as the paragons of virtue, but are exactly the opposite.

Image Credits: 1 John Tyler (Wikipedia.org) 2 Judge Tyler, Sr. (Wikipedia.org) 3 Greenway Plantation (Wikipedia.org) 4 Tippecanoe and Tyler Too Score (Wikipedia.org) 5 Hard Cider and Log Cabin Emblem (Wikipedia.org) 6 William Henry Harrison (Wikipedia.org) 7 Death of Harrison (Wikipedia.org) 8 Letitia Tyler (Wikipedia.org) 9 Julia Tyler (Wikipedia.org) 10 Tyler receives news of Harrison’s death (Wikipedia.org) 11 Sherwood Plantation (Wikipedia.org)