“Preach the word; be ready in season and out of season; reprove, rebuke, exhort, with great patience and instruction. For the time will come when they will not endure sound doctrine.”

—II Timothy 4:2,3

Thomas Watson’s Farewell, August 17, 1662

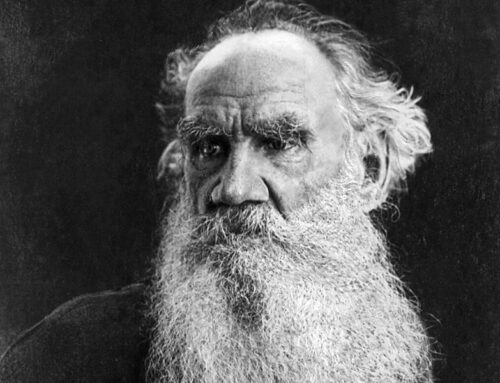

![]() homas Watson was one of the best known and most reprinted preachers in England’s history. On August 17, 1662 he preached his last sermon to the congregation he had served as pastor for the previous sixteen years, St. Stephens, Walbrook. Little is known of his early years or personal history, but we assume his birth around 1620 in Yorkshire. He first appears as a student at Emmanuel College, Cambridge, where tradition says he was an intense scholar, completing his Master of Arts in 1642. Watson’s life parallels in the same time period many famous Puritan preachers in Britain—John Owen, Richard Baxter, Thomas Brookes, John Bunyan, Robert Traill, Samuel Rutherford, and many others of note.

homas Watson was one of the best known and most reprinted preachers in England’s history. On August 17, 1662 he preached his last sermon to the congregation he had served as pastor for the previous sixteen years, St. Stephens, Walbrook. Little is known of his early years or personal history, but we assume his birth around 1620 in Yorkshire. He first appears as a student at Emmanuel College, Cambridge, where tradition says he was an intense scholar, completing his Master of Arts in 1642. Watson’s life parallels in the same time period many famous Puritan preachers in Britain—John Owen, Richard Baxter, Thomas Brookes, John Bunyan, Robert Traill, Samuel Rutherford, and many others of note.

Thomas Watson (c. 1620–1686)

Emmanuel College Chapel, Cambridge

Watson began his ministry in the household of Lady Mary Vere, the widow of Sir Horace Vere, baron of Tilbury. Calling a young minister to preach and teach in a nobleman’s estate gave a young man his first experience in the ministry as well as a steady income and confirmation of his divine calling. Sometimes, in days of persecution, private ministry was a means of protection from government interference. In 1646 he accepted the very public call to St. Stephens. His ministry reached far beyond his own congregation as his sermons were often published and series became books. His erudition, simplicity, and practical applications are still helpful and eagerly studied among Reformed preachers to this very day. Watson was beloved and oft quoted by that “prince of preachers,” Charles Haddon Spurgeon, in the 19th Century.

The former Stocks Market in central London showing St Stephen Walbrook church in the back right of the painting, as well as a statue in the forefront of King Charles II mounted on a horse and trampling Oliver Cromwell

The First English Civil War erupted as a struggle between Parliament and King Charles I, in the year that Watson finished his degree at Cambridge. By the time he accepted the call to St. Stephens, the King had lost the war and was held for disposition by Parliament and the army. Watson married at that time, the daughter of another pastor, and over his lifetime had seven children. The harmony and accord of the Westminster Assembly which had produced the Westminster Confession of Faith by 1647, masked the party spirit that divided the kingdom politically, over the next several years. The Scots and the presbyterian party in Parliament, including a number of Puritan divines, Watson among their number, believed the King should be restored, but without authority to dictate to the church how they should conduct the worship of God.

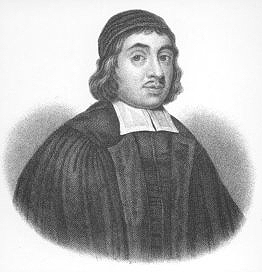

Christopher Love (1618-1651), Puritan minister executed by Parliament in 1651 for his support of the restoration of Charles II

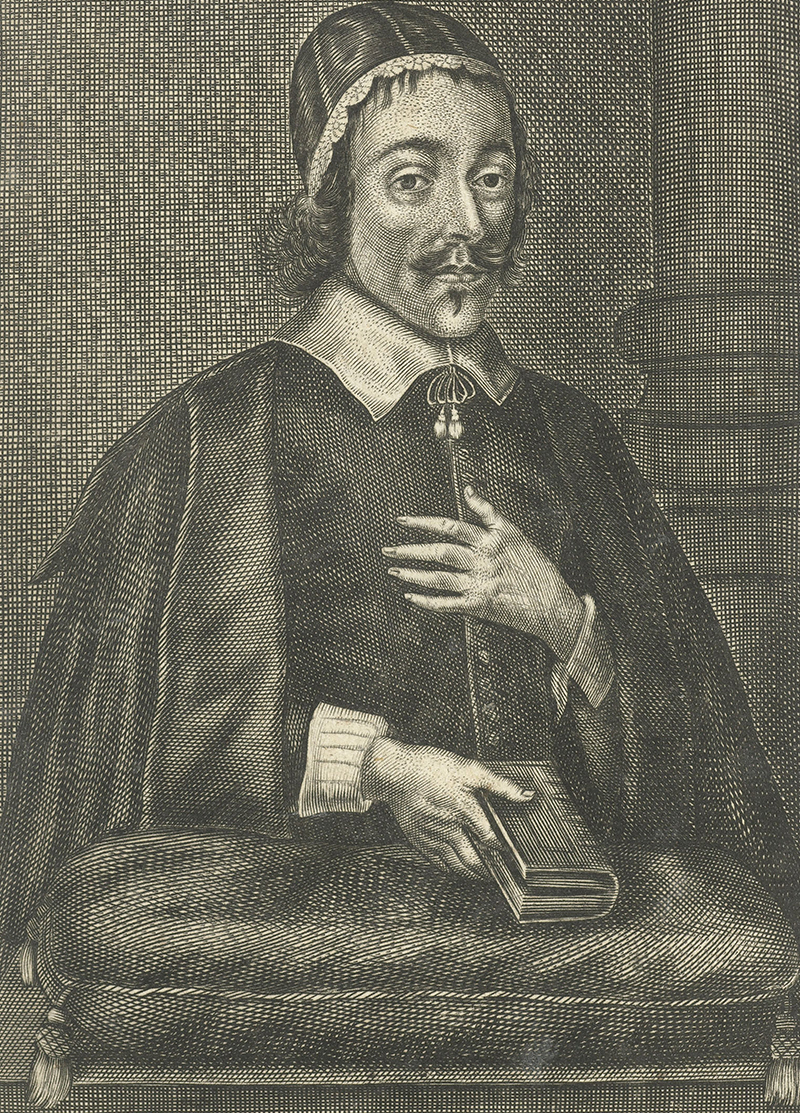

Watson appeared before Oliver Cromwell, the head of the Army, to protest the execution of Charles I. In 1651 Watson was arrested and imprisoned with several other pastors for corresponding with Charles II, hoping to restore the monarchy. The Parliament executed Pastor Christopher Love for treason, but pardoned Thomas Watson upon his petition for mercy. He returned to his ministry in Walbrook in 1652, and gained great renown for his preaching and teaching for ten more years. Watson was among the 2,000 ministers ejected from their pulpits in 1662 for rejecting the Act of Uniformity issued by Charles II. Ironically, the very King with whom Watson had conspired to return the throne to the Stuart monarchy, forced the Anglican Prayer Book and liturgy on all the churches.

Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658)

Charles II (1630-1685)

Watson preached several farewell sermons to his congregation before his ejection the third week of August, 1662. Among his last words to his beloved people were these:

“Every day think upon eternity. Oh, eternity, eternity! All of us here are, ere long—it may be some of us within a few days or hours—to launch forth into the ocean of eternity….The thoughts of eternity would make us very serious about our souls….Oh how fervently would that man pray that thinks he is praying for eternity. Oh how accurately and circumspectly would that man live who thinks that upon this moment hangs eternity….The thoughts of eternity would keep us from grieving overmuch at crosses and sufferings of the world. Our sufferings, says the apostle, are but for a while. What are all the sufferings we can undergo in the world in comparison with eternity? Affliction may be lasting, but it is not everlasting. Our sufferings are not to be compared to an eternal weight of glory.”

Crosby Hall, where Watson held services for some time following the Declaration of Indulgence

Watson continued to preach secretly in private for ten years—in barns, homes, and woods. After the Great Fire of London in 1666 he prepared a large room for public worship and welcomed all who wished to attend, risking fines and imprisonment. With the Declaration of Indulgence in 1672, Watson, one of the best known nonconformists, obtained a license for “Crosby Hall” and continued to preach. He was joined by Stephen Charnock for several years. He died in Barnston in 1686 while in earnest prayer, a practice for which he was well known, even by Anglican bishops! He was buried there beside his father.

The church and churchyard of St. Andrews in Barnston, Essex

Thomas Watson’s books and sermons have remained among the favorites of both pastors and laymen who have read and studied the best of the Puritan fathers of the 17th Century, especially his works on The Lord’s Prayer, The Ten Commandments, and The Beatitudes, as well as particular individual sermons. Watson will likely be read as long as there are faithful Reformed pastors.

Image Credits: 1 Thomas Watson (Wikipedia.org) 2 Emmanuel College Chapel, Cambridge (Wikipedia.org) 3 Stocks Market London (Wikipedia.org) 4 Oliver Cromwell (Wikipedia.org) 5 Charles II (Wikipedia.org) 6 Christopher Love (Wikipedia.org) 7 Crosby Hall (Wikipedia.org) 8 St Andrews, Barnston (Wikipedia.org)