“And he shall judge among the nations, and shall rebuke many people: and they shall beat their swords into plowshares, and their spears into pruninghooks: nation shall not lift up sword against nation, neither shall they learn war any more.” —Isaiah 2:4

Custer’s Last Stand, June 25, 1876

![]() he Battle of the Little Bighorn on June 25, 1876 produced more shock to the American people and more interest and writing than any other battle between “Native” Americans and government soldiers in American history. Neither interest in the battle, nor the re-telling, have abated over the past 143 years. How much more information can be gleaned that a hundred books have not already recorded? What more can the Custer battlefield tell us about what happened there? Like the annual publishing of new books on RMS Titanic and the Battle of Gettysburg, there is an unending fascination with the story, with new insights and new information. When an event grabs the imagination of an entire nation and keeps its power through a kind of multi-generational historical DNA, we will never put it to rest. Such is “Custer’s Last Stand”.

he Battle of the Little Bighorn on June 25, 1876 produced more shock to the American people and more interest and writing than any other battle between “Native” Americans and government soldiers in American history. Neither interest in the battle, nor the re-telling, have abated over the past 143 years. How much more information can be gleaned that a hundred books have not already recorded? What more can the Custer battlefield tell us about what happened there? Like the annual publishing of new books on RMS Titanic and the Battle of Gettysburg, there is an unending fascination with the story, with new insights and new information. When an event grabs the imagination of an entire nation and keeps its power through a kind of multi-generational historical DNA, we will never put it to rest. Such is “Custer’s Last Stand”.

The Custer Fight, by Charles Marion Russell

The Civil War had ended eleven years earlier. The “Reconstruction” of the South would come to an end after the elections in November of that Centennial year. Most of the career soldiers who wished to remain in the greatly reduced Union armies had to accept lesser rank and could look forward to either boring garrison duty or action against the Indian tribes of the plains. Hard men like William T. Sherman, Philip Sheridan, and George Crook were sent west to implement the “Indian policies”, and herded the plains tribes onto government set-aside reservations; they often killed the ones who resisted.

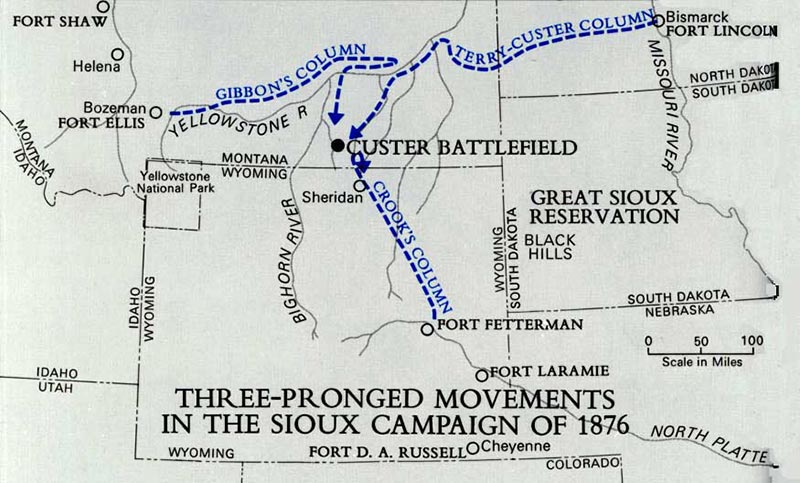

1876 Army Campaign against the Sioux

Independent-minded Lakota Sioux, Cheyenne, Arapahos and Dakotas decided that reservation life was not for them, and buffalo hunting season was upon them, so they made a run for it. They followed their spiritual leader Sitting Bull and warrior-chiefs like Crazy Horse, Gall, and Lame White Man into Montana, across the Little Bighorn River into an area popularly known as the “greasy grass”. The warriors, women and children hauled their teepees and camps across the plains, perhaps eight thousand people in a thousand lodges.

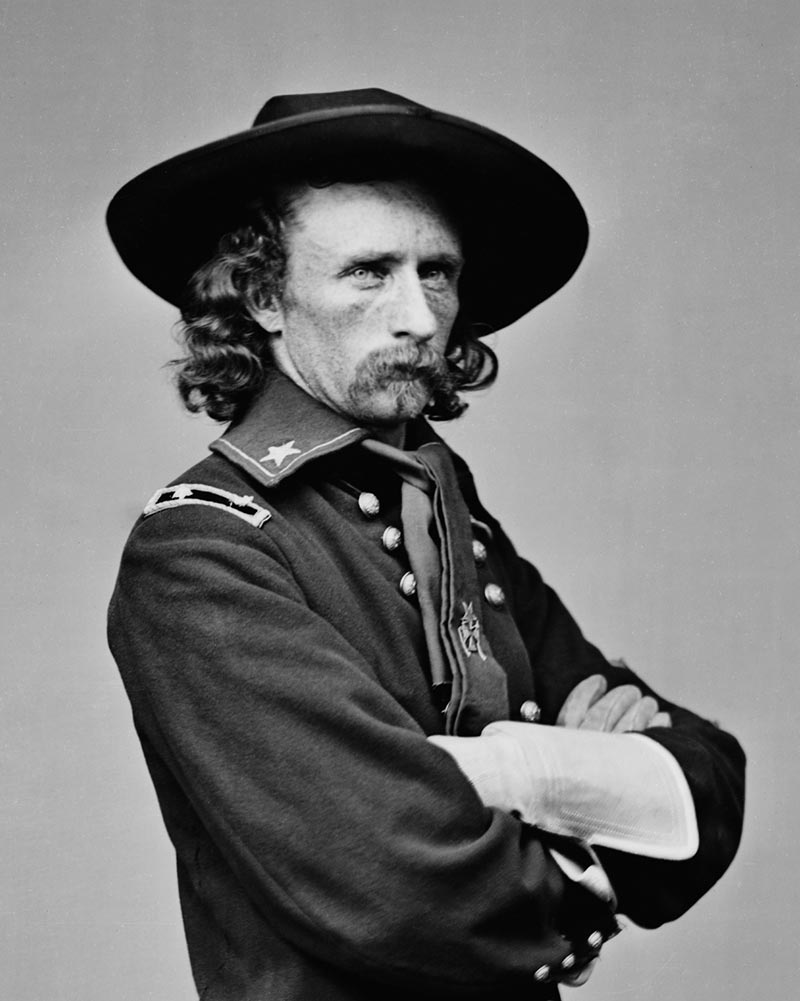

Brevet Major General George Armstrong Custer (1839-1876)

Impetuous and vain, Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer, a Union Civil War hero and former general at age twenty-three, longed for action against the “hostiles”. He held command of most of twelve companies of the 7th Cavalry, which had been formed after the Civil War. They had left Fort Abraham Lincoln on May 17, part of a massive three-pronged offensive against the wayward tribes. Custer quickly outstripped his substantial supply train and Gatling guns, led by his allied Crow tribal scouts, in order to move swiftly to find the hostiles first. He succeeded.

Rather than wait for the other army column that was moving in his direction, Custer decided to attack the enormous encampment by himself. He divided his command into three segments, the other two commanded by Captain Frederick Benteen, with 3/12 companies and Major Marcus Reno, with 5 companies. Custer’s estimate of the number of warriors he faced was well out of date. The combined forces of the several tribes totaled more than 1,500 — perhaps the largest Indian army ever assembled.

Battle of the Little Bighorn movements of the 7th Cavalry

A: Custer B: Reno C: Benteen D: Yates E: Weir

Custer, leading five companies, rode to attack the village, possibly to secure non-combatant hostages; the warriors raised the alarm and rode to protect their families. Major Reno’s troopers made first contact. They dismounted and began firing into the village, allegedly killing a few women and children. The Indians did not run as expected. Reno’s force was assailed on flank and front by about five hundred warriors, causing the Major and as many as could to flee to the bluffs across the river, taking casualties all the way. Benteen reinforced Reno, and their hastily prepared defenses held out to the end of the fight.

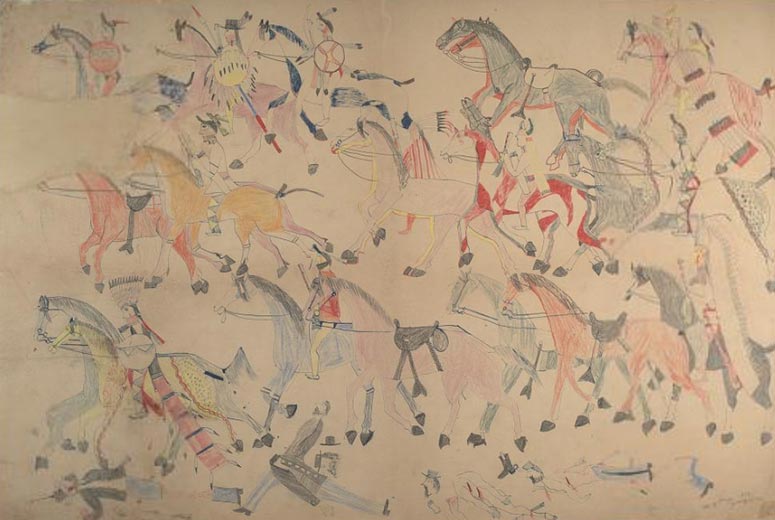

Lakota depiction of casualties at The Battle of Little Bighorn

Custer, on the other hand, with his roughly 210 men fought to the death, and had no survivors. The “yellow hair” as he was known by the Sioux, along with two of his brothers, a nephew and brother-in-law were killed along with about 260 other 7th Cavalry troopers. Congressional investigations, newspaper articles, and recriminations followed the fight. The battle was called a massacre in the press, exaggerating the nature of frontier combat, to put the worst light on the tribes. Most of the Indians returned to their reservations over the next couple months as the army assembled a force of more than 2,000 troops to track down any who did not comply. The Battle of the Little Bighorn was the last major action of the Sioux Wars, but did not put an end to bloodshed on the rapidly disappearing frontier.

Monuments to those who fell at the Battle of the Little Bighorn

The uneasy relations between the American government and the inhabitants of the western prairies rarely brought peace to the natives and certainly not satisfaction. As the victims of “manifest destiny”, the tribes of the plains could never reconcile their history and worldview with the beliefs and culture of the newly empowered centralized state, following a rapidly secularizing, evolutionary American territorial expansion. Both sides committed atrocities and broke treaties. The Little Bighorn solved nothing, but demonstrated that arrogance and battle-lust on the part of a technologically superior commander and his forces could not overcome primitive men, accustomed to hardship and defending their families, at least on June 25, a hundred years after the creation of the American Republic.