Mexican Reinforcements Arrive at the Alamo, February 27, 1836

![]() he Siege of the Alamo in San Antonio de Bexar lasted from February 23 to March 6, 1836. Many people know how it ended in the assault and destruction of the garrison in the Spanish mission-turned-fortress, and the longer outcome of Texas independence, eventual statehood, and preeminent place in American history. Fewer know about the reinforcements that considered going to the Alamo’s aid, and those handful who actually joined the garrison, and with them, Texas immortality.

he Siege of the Alamo in San Antonio de Bexar lasted from February 23 to March 6, 1836. Many people know how it ended in the assault and destruction of the garrison in the Spanish mission-turned-fortress, and the longer outcome of Texas independence, eventual statehood, and preeminent place in American history. Fewer know about the reinforcements that considered going to the Alamo’s aid, and those handful who actually joined the garrison, and with them, Texas immortality.

“Ruins of the Church of the Alamo, San Antonio de Bexar”, an 1847 watercolor by Edward Everett who painted the piece while stationed in San Antonio during the Mexican-American War

After several years of negotiation with the Mexican authorities, Stephen F. Austin, a native of Wythe County, Virginia, led three hundred American families to settle in the Mexican province of Texas in 1825. The government in Mexico City at that time was a Federal Republic, based on the Mexican Constitution of 1824. In 1835 a military dictator, Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna suspended the Constitution and created a centralized state, of which the province of Texas was a part. The Texians (as they called themselves), rebelled, as did several other Northern provinces, demanding independence. In Texas, they seized the old mission station known as the Alamo in San Antonio, over the first two weeks of December. Texians organized militias for defense across the region, made up of native Mexicans and American immigrants. Representatives of the settlements met in San Felipe in November, and appointed Sam Houston, a veteran soldier and respected leader, in charge of the yet unraised regular army. They called for volunteers but gave Houston no money or supplies.

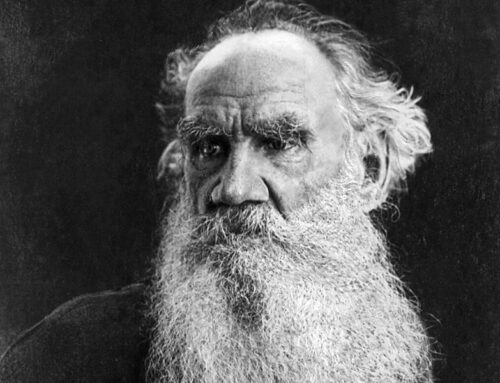

Stephen F. Austin (1793-1836) known as the “Father of Texas”

In addition to Texas, numerous other independence movements sprang up in the period between 1835-1936

The Alamo Mission station, now a hastily converted fort, covered three acres, with a surrounding wall of nine to twelve feet high, surrounding about thirteen hundred linear feet. By February, the fort was under the joint command of South Carolinian William Barrett Travis, a regular army officer, and militia leader, Kentuckian James Bowie, a rough and tumble frontiersman with a checkered past. On February 16, unknown to the Alamo garrison, Santa Anna crossed the Rio Grande River at the head of about 1,500 troops, determined to crush the rebellion. Only 156 men manned the fort, with fourteen in the hospital.

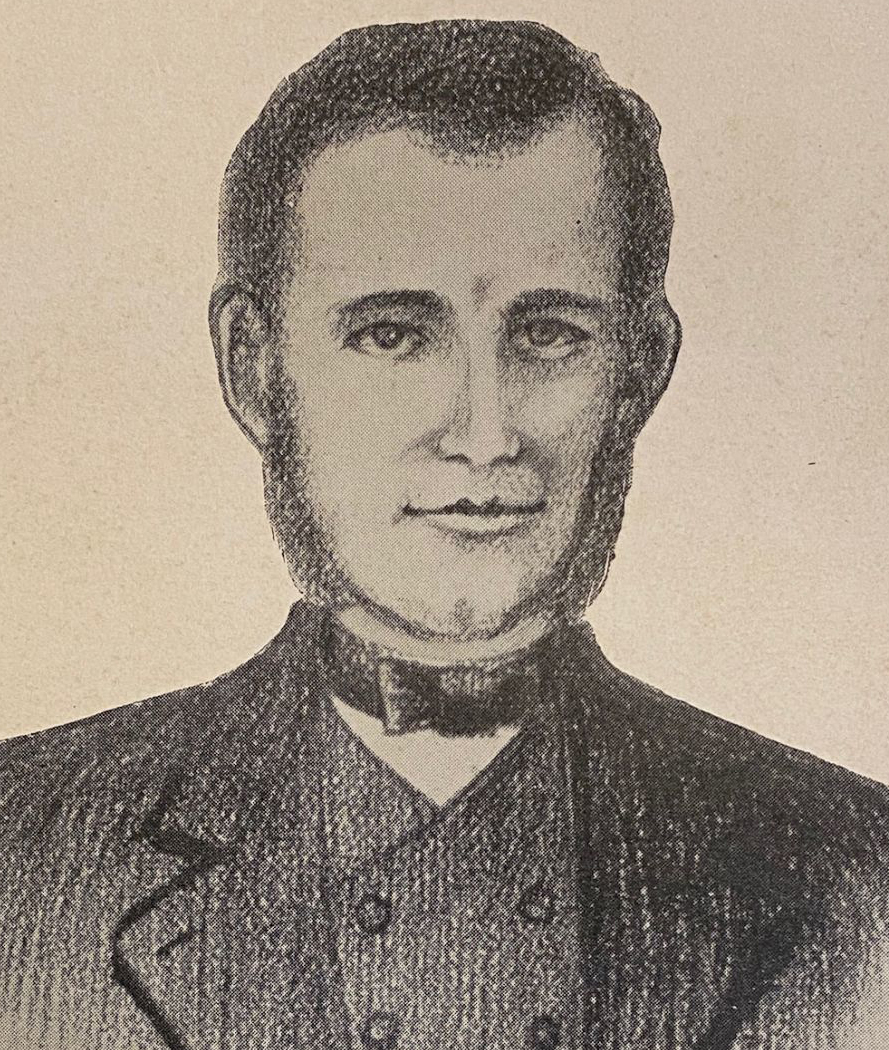

This sketch of William Barret Travis (1809-1836) is the only known likeness of him created during his lifetime

While the people of Bexar and the men of the Alamo celebrated George Washington’s birthday on February 21, Santa Anna sent Colonel Sesma with a cavalry strike force to catch the garrison out of their fort and dancing in the streets. As Providence would have it, a downpour of rain flooded the banks of the Medina River, only twenty-five miles away, preventing the Mexican horsemen from crossing the river. The confrontation would have to await a more dramatic and consequential moment in time. Two days later, the Texians spotted the Mexican army across the prairie, herded cattle into the fort, lay in stocks of corn and awaited the arrival of Santa Anna.

Antonio López de Santa Anna (1794-1876)

Travis dispatched a scout to request Colonel Fannin with several hundred men one hundred miles away and two riders to the town of Gozales where more militia and supplies could be brought to reinforce the beleaguered post at San Antonio. After flying the flag of “no quarter” by the Mexicans, and an exchange of cannon fire, the two sides settled in for what would prove not to be a protracted siege. Four scouts who were out when the enemy arrived were unable to get into the fort and rode away.

Col. James Fannin (1805-1836)

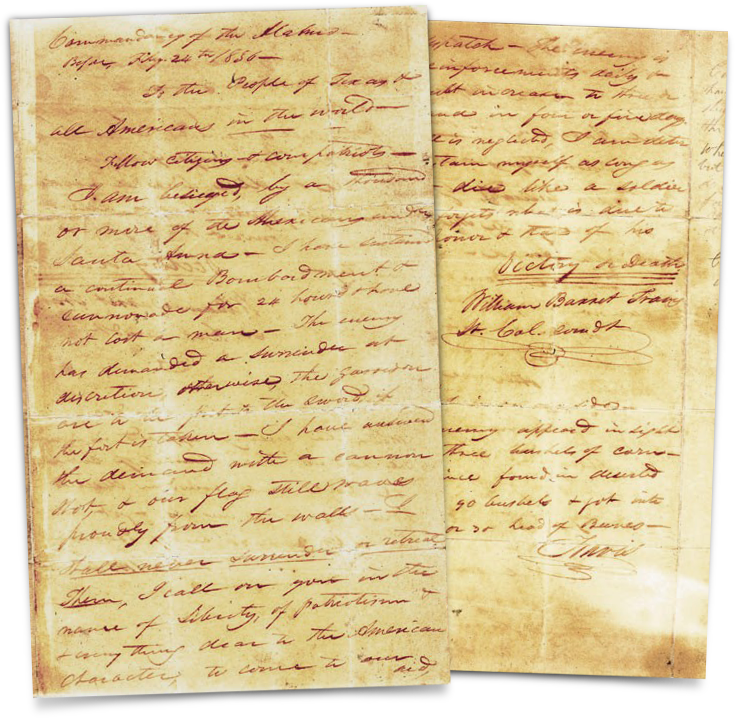

Another courier slipped out of the fort and rode to Gonzales with the following message, which was then raced up to San Felipe to the governor:

To the People of Texas & all Americans in the World—

Fellow citizens & compatriots—I am besieged, by a thousand or more of the Mexicans under Santa Anna—I have sustained a continual Bombardment & cannonade for 24 hours & have not lost a man. The enemy has demanded a surrender at discretion, otherwise, the garrison are to be put to the sword, if the fort is taken—I have answered the demand with a cannon shot, & our flag still waves proudly from the walls. I shall never surrender or retreat. Then, I call on you in the name of Liberty, of patriotism & everything dear to the American character, to come to our aid, with all dispatch—The enemy is receiving reinforcements daily & will no doubt increase to three or four thousand in four or five days. If this call is neglected, I am determined to sustain myself as long as possible & die like a soldier who never forgets what is due to his own honor & that of his country—

Victory or Death

William Barret Travis

Lt. Col. comdt

Letter written by Travis seeking reinforcements and supplies

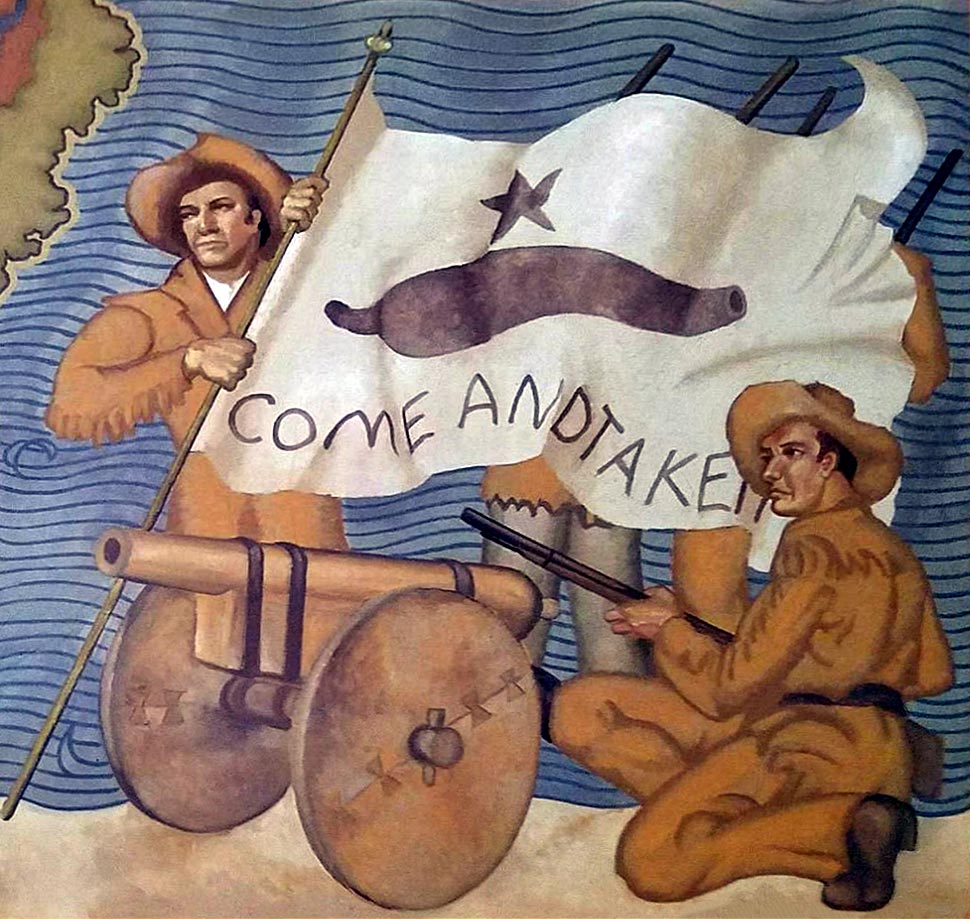

Volunteers across Texas assembled at various points, although the government was in no position to send relief. An army of militia groups began assembling at Gonzales. On February 26, Col. Fannin started out for the Alamo with 350 men and four cannon from Goliad, ninety miles away. After two days of travel, the relief column had travelled less than a mile from their fort. Their oxen had wandered off, wagons broke down, a freezing rain made the men miserable, they didn’t have enough food, reports said another Mexican army was headed their way– the expedition was called off. Twenty-five men from Gonzales set off for the Alamo, soon joined by eight more. They carried the “Come and Take It” flag from an earlier confrontation in Gonzales between Mexican dragoons and the first Texians to face off against them. They snuck through Mexican lines and joined the garrison. The next day Santa Anna received 1,000 reinforcements.

Detail of a mural in the Gonzales Memorial Museum

“The Fall of the Alamo” also known as “Crockett’s Last Stand” is house in the Texas Governor’s Mansion in Austin

On March 6, the Mexican army struck before dawn, after bombardment with artillery the day before. Overwhelming the guards and swarming over the walls, after two brief repulses. The battle likely lasted less than an hour as all the defenders were tracked down and killed. Any who attempted to escape to the prairie were trapped and killed by the excellent Mexican cavalry who had been stationed outside for just such a purpose. All the defenders perished and are remembered today in legend, monuments, and scores of books on the Alamo and Texas independence.

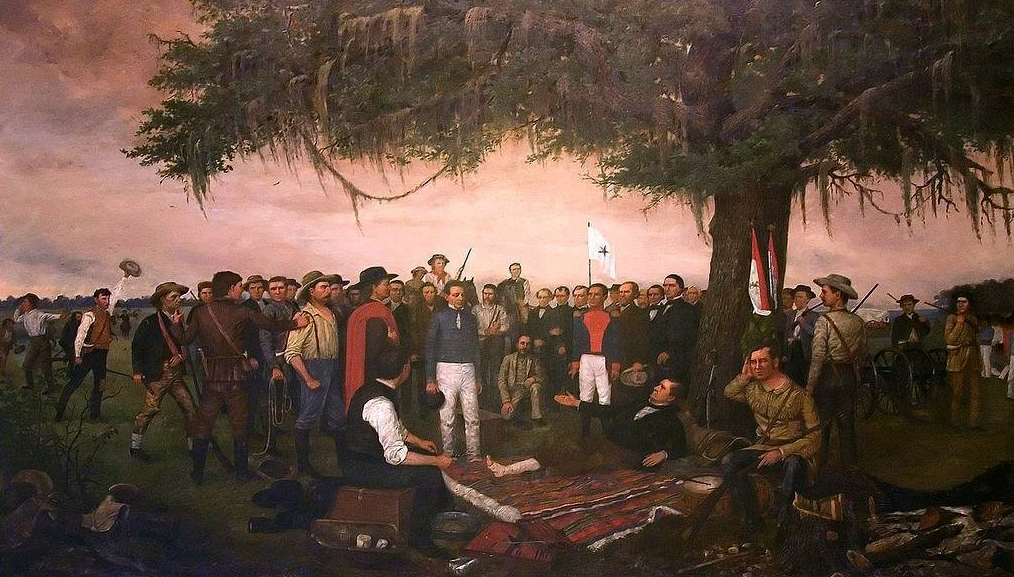

This 1886 painting depicts the end of the Texas Revolution where Mexican General Santa Anna surrenders to a wounded Sam Houston following the 1836 Battle of San Jacinto

Visit the major sites of Texas independence with us March 28-30. The educational & political powers of modernity are changing Texas history to conform to a new narrative. Visit the sites before the political pressures erase the memory of the sacrifices made for liberty. Learn More >

Image Credits: 1 Alamo Watercolor (Wikipedia.org) 2 Stephen F. Austin (Wikipedia.org) 3 Independence Movements Map (Wikipedia.org) 4 William Barret Travis (Wikipedia.org) 5 Santa Anna (Wikipedia.org) 6 Col. James Fannin (Wikipedia.org) 7 Travis Letter (Wikipedia.org) 8 Museum Mural (TripAdvisor.com) 9 Fall of the Alamo (Wikipedia.org) 10 Surrender of Santa Anna (Wikipedia.org)