“Pride goes before destruction

And a haughty spirit before stumbling

—Proverbs 16:18

The Battle of Waterloo, June 18, 1815

![]() o individual in history so dominated the continent of Europe as did Napoleon Bonaparte from 1800-1815. He seemed to be the embodiment of the “Great Man Theory” that became prominent in the 1840s—that highly skilled and brilliant but violent leaders so dominated certain eras that other explanations to describe the stream of western civilization seem inadequate. Alexander the Great, Julius Caesar, and Napoleon made the most of their brief appearances on the stage of history. And they all received their providential comeuppance. Bonaparte’s came in a lowly corner of what is today Belgium, a place known as Waterloo.

o individual in history so dominated the continent of Europe as did Napoleon Bonaparte from 1800-1815. He seemed to be the embodiment of the “Great Man Theory” that became prominent in the 1840s—that highly skilled and brilliant but violent leaders so dominated certain eras that other explanations to describe the stream of western civilization seem inadequate. Alexander the Great, Julius Caesar, and Napoleon made the most of their brief appearances on the stage of history. And they all received their providential comeuppance. Bonaparte’s came in a lowly corner of what is today Belgium, a place known as Waterloo.

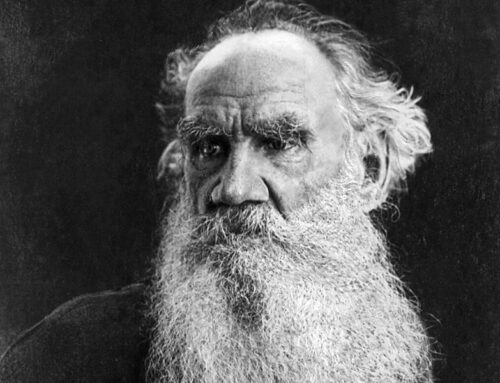

The Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821) in His Study at the Tuileries, 1812

The Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821) in His Study at the Tuileries, 1812

Fifteen years earlier, almost to the day, Napoleon had defeated the Austrians at the Battle of Marengo, which solidified his hold on Paris as the “1st Consul,” a position he had assumed the previous November in a coup d’état. His army secured their dominant position over the pretensions of other French generals, and Napoleon Bonaparte began what became a fifteen-year military conquest of Europe, piling up between 3.5 to 6.5 million dead, civilian and military combined. The total does not count those who perished in the French Revolutionary wars, which actually began in 1792. During those first fifteen years of the 19th Century, grand coalitions of European nations combined to fight Revolutionary France, resulting in Napoleon’s disastrous invasion of Russia and penultimate defeat by five armies, “The Sixth Coalition.” He abdicated the throne in April, 1814, and was exiled by the victors to the Island of Elba.

The Battle of Marengo (June 14, 1800) was Napoleon’s first significant victory as head of state

The Battle of Leipzig, October 16-19, 1813—one of numerous conflicts between Napoleon’s forces and the allies of the Sixth Coalition including forces from Austria, Prussia, Russia, the United Kingdom, Portugal, Sweden, Spain and a number of German states. The battle was the largest in European history before WWI, and the Coalition victory resulted in Napoleon’s exile to Elba.

The Battle of Leipzig, October 16-19, 1813—one of numerous conflicts between Napoleon’s forces and the allies of the Sixth Coalition including forces from Austria, Prussia, Russia, the United Kingdom, Portugal, Sweden, Spain and a number of German states. The battle was the largest in European history before WWI, and the Coalition victory resulted in Napoleon’s exile to Elba.

Separated from his family, without the promised income, and angry at rumors that he would be sent to an island far away from France, Napoleon escaped from Elba, joining seven hundred followers, and landed in France. When word got out that the Emperor had returned, King Louis XVIII sent Bonaparte’s greatest general Marshall Ney and a regiment of troops to round up the miscreant and his entourage. In the event, when the troops spotted Napoleon, alone, trudging up a dirt road, they shouted “Vive L’empereur,” and Ney, having boasted he’d bring him back in an iron cage, dismounted and kissed Napoleon. Together they marched on Paris, the King fled the country, and the Congress of Vienna declared Napoleon Bonaparte an outlaw. He swiftly became an outlaw with a 200,000-man army.

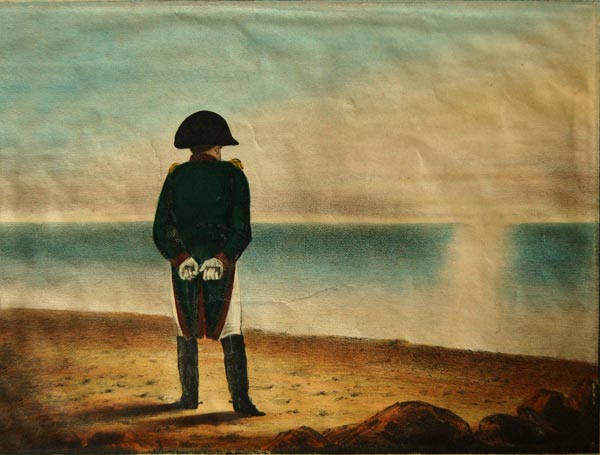

Napoleon exiled on the Island of Elba, a small island just off the northwestern coast of Italy

After Napoleon’s forced abdication following the Treaty of Fontainebleau, he was exiled to Elba. He remained there only ten months before his escape on February 26, 1815, depicted above.

After Napoleon’s forced abdication following the Treaty of Fontainebleau, he was exiled to Elba. He remained there only ten months before his escape on February 26, 1815, depicted above.

The new European coalition came after him, and the armies of two countries, Great Britain and Prussia, met the French army and their restored emperor at Waterloo on June 15, 1815. Napoleon planned to defeat his foes in detail, considering the Prussians inexperienced and led by a superannuated septuagenarian Field Marshall Gebhard von Blücher and the British, who had sent their best troops to fight the Americans in the War of 1812 (Battle of New Orleans), but were nonetheless led by their best General Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington.

Gebhard von Blücher (1742-1819)

Château d’Hougoumont, a walled farm compound near Waterloo, Belgium, served as a defensible position for the Anglo-allied army under the Duke of Wellington

Château d’Hougoumont, a walled farm compound near Waterloo, Belgium, served as a defensible position for the Anglo-allied army under the Duke of Wellington

The British commander marched his men from Brussels to Waterloo and positioned them along a sunken road with his flanks anchored on a stout chateau called Hougoumont and its gardens and orchard and the other flank in the hamlet of Papelotte. Because the battlefield was only two and a half miles wide, he was able to line up many of his men in depth behind hills where they could not be seen. He had at his command about 30,000 British soldiers and 37,000 German and Dutch allies, along with 156 cannons. If Blücher’s Prussians arrived in time for battle, it would add another 50,000 men. Napoleon commanded about 73,000 French troops. When Marshall Soult expressed some dissatisfaction at the French deployments, Napoleon told him that Wellington was a bad general, the “English are bad troops, and this affair is nothing more than eating breakfast.”

Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington (1769-1852)

Due to a providential all-night rain, the field was soaked, causing Napoleon to delay his attack and thus giving Blücher more time to get his army to the battlefield. Around 10:00am the attack began, the battle focusing on the capture of the Huogoumont. Both sides fed troops into that part of the field throughout the day, eventually totaling about 30,000 soldiers. The British held the chateau to the end. Around noon, the French Grand Battery of eighty guns began shelling the British center causing many casualties, though some of the artillery rounds buried in the wet ground and did not explode.

Marshal General Jean-de-Dieu Soult (1769-1851), 1st Duke of Dalmatia

Marshal General Jean-de-Dieu Soult (1769-1851), 1st Duke of Dalmatia

Marshal Ney leading the French cavalry charge at Waterloo

Marshall Ney led the grand infantry assault on the English center, focused on a walled farmhouse called La Haye Sainte. As the French infantry broke through the center of the British line, Wellington unleashed the heavy cavalry “gallop at everything, never consider the situation, or think of manoeuvring.” They chopped down the French infantry and continued across the field, losing all coherence and into the guns of the grand battery. The service rendered came at a high cost, as did every aspect of the day’s fighting. More than half of the cavalry did not return, upon the French counterattack by their Cuirassier’s. The French cavalry were in turn shot to pieces by the British squares of infantry. Horses will not throw themselves on hedges of bayonets, but can in turn be shot by infantry in such formations.

Michel “Marshall” Ney (1769-1815), French military commander who fought in the French Revolutionary Wars and the Napoleonic Wars

The storming of La Haye Sainte

La Haye Sainte finally fell to the French infantry and Wellington, trapped in an infantry square said “Blücher or nightfall must come.” As Providence would have it, Blücher arrived on the French flank before nightfall. One final attempt by Napoleon’s Old Guard to win the day failed, and the army broke to pieces. About 17,000 allies lay dead or wounded on the field and about 25,000 French. Napoleon’s last bid for power had failed in one of the mightiest, bloodiest and decisive battles of European history. It ended the French First Empire and proved a turning point in history. Napoleon was again exiled, to the Island of St. Helena, where he died six years later.

Napoleon spent his final six years in exile on the Island of Saint Helena, some 1,200 miles off the southwestern coast of Africa

The painting Scotland Forever! depicts the Royal Scots Greys charging at the Battle of Waterloo

At the 200th Commemoration of Waterloo (Bicentennial) in 2015, Belgium minted a two-Euro coin commemorating the battle. French protest resulted in Belgium melting them down, never issued. They made a successful unlooked-for flank attack, however, by issuing an identical non-standard issue commemorative coin for 2.5 Euros, valid only in the issuing country, but sold for 6 euros. English General Wellesley, known as Wellington, remains one of the greatest generals of history, Napoleon one of the greatest tyrants.

2.5 Euro coin minted in Belgium commemorating the bicentennial of the Battle of Waterloo

Image Credits: 1 Napoleon in his study (Wikipedia.org) 2 The Battle of Marengo (Wikipedia.org) 3 The Battle of Leipzig (Wikipedia.org) 4 Napoleon in exile on Elba (Wikipedia.org) 5 Escape from Elba Island (Wikipedia.org) 6 Gebhard von Blücher (Wikipedia.org) 7 Hougoumont during the Battle of Waterloo (Wikipedia.org) 8 Duke of Wellington (Wikipedia.org) 9 Jean-de-Dieu Soult (Wikipedia.org) 10 Ney at Waterloo (Wikipedia.org) 11 Marshall Ney (Wikipedia.org) 12 The Storming of La Haye Sainte (Wikipedia.org) 13 Royal Scots Greys (Wikipedia.org) 14 Commemorative Coins (CoinWorld.com)