“When the righteous are in authority, the people rejoice: but when the wicked beareth rule, the people mourn.” —Proverbs 2:29

The Declaration of Independence,

July 4, 1776

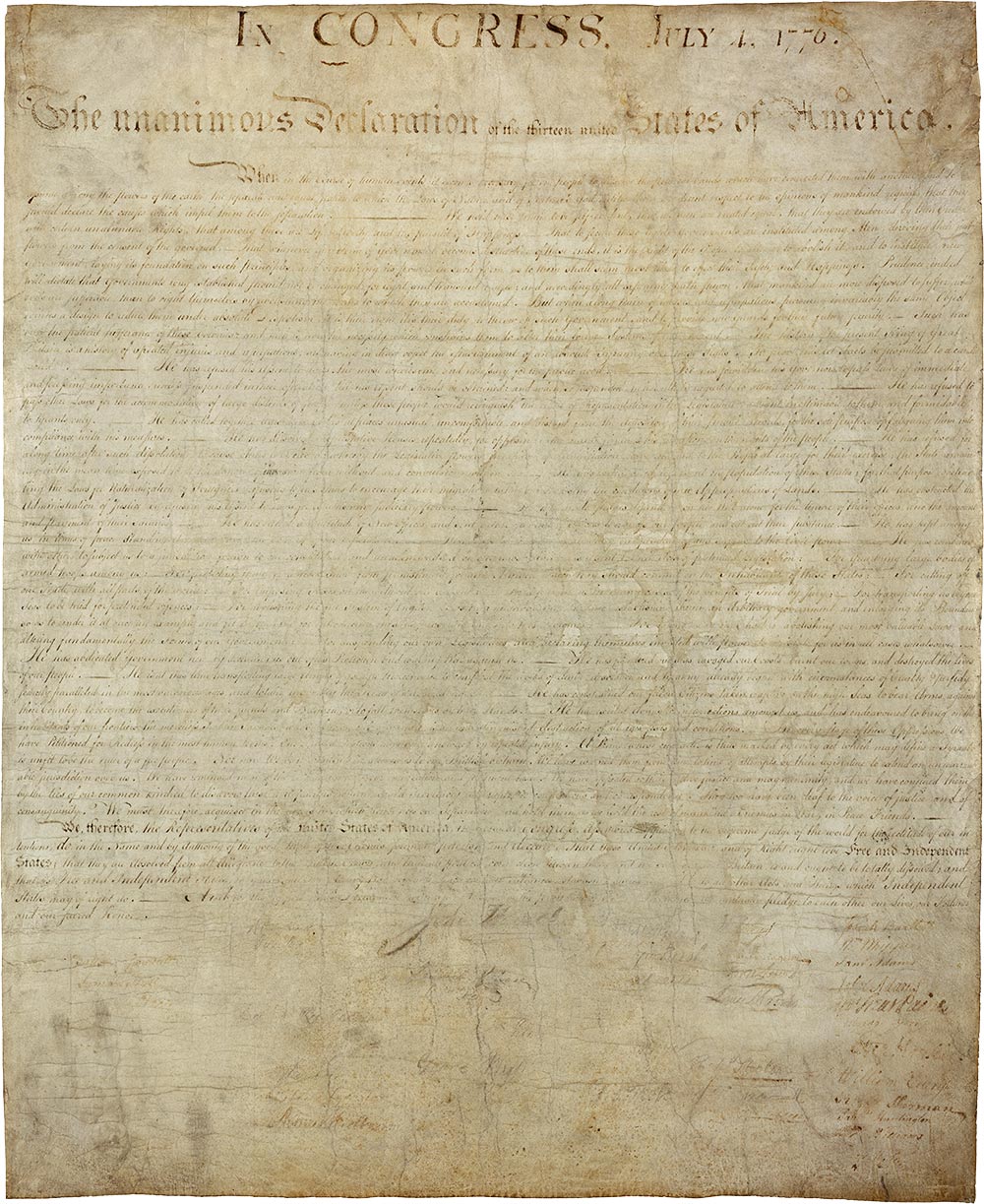

![]() he Declaration of Independence is just that—a declaration of formal separation or secession from Great Britain, the final wording approved by the Second Continental Congress on July 4, 1776. They listed the reasons for separation, in summary form, having already been at war with the Mother Country for more than a year. The document was signed in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania by fifty-six State Representatives of thirteen British Colonies: Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, Virginia, Maryland, Delaware, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, New York, Rhode Island, Connecticut, Massachusetts, and New Hampshire.

he Declaration of Independence is just that—a declaration of formal separation or secession from Great Britain, the final wording approved by the Second Continental Congress on July 4, 1776. They listed the reasons for separation, in summary form, having already been at war with the Mother Country for more than a year. The document was signed in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania by fifty-six State Representatives of thirteen British Colonies: Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, Virginia, Maryland, Delaware, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, New York, Rhode Island, Connecticut, Massachusetts, and New Hampshire.

The signed copy of the Declaration, on display at the National Archives in Washington, DC

The signed copy of the Declaration, on display at the National Archives in Washington, DC

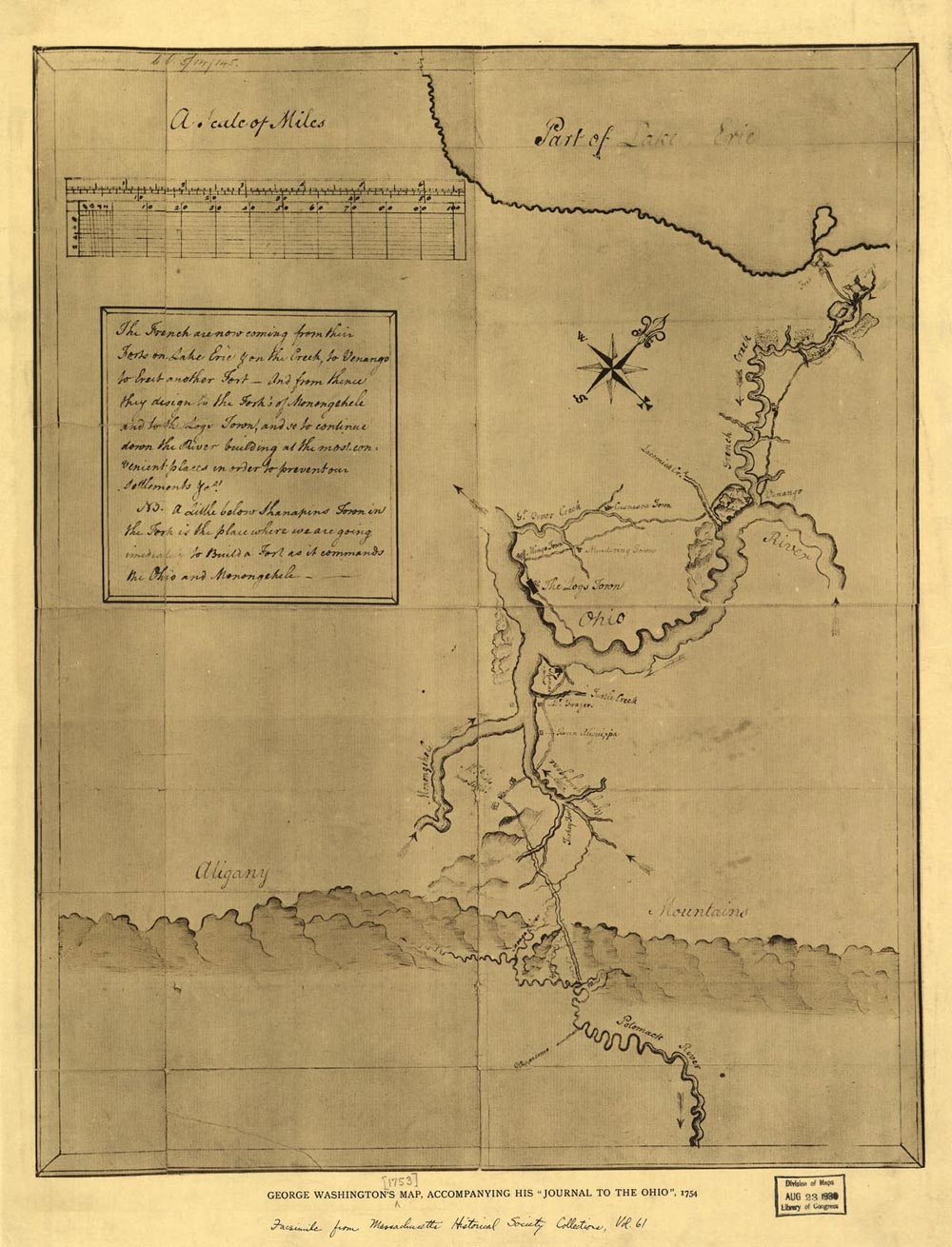

When the French and Indian War (Seven Years’ War) ended in 1763, Britain was presented with a new set of foreign policy problems. Native Americans west of the Alleghenies continued to prefer their own control of the Ohio Valley and Kentucky hunting grounds, over ceding them to American frontiersmen and their families. The size of the British Empire had suddenly doubled, and troops were required to maintain order. British politicians proclaimed that the American colonies needed to continue their submission to the principles of profit for the Mother Country, as set down in the Navigation Laws and Mercantilism.

A map sketched by George Washington accompanying his “Journal to the Ohio”, 1754

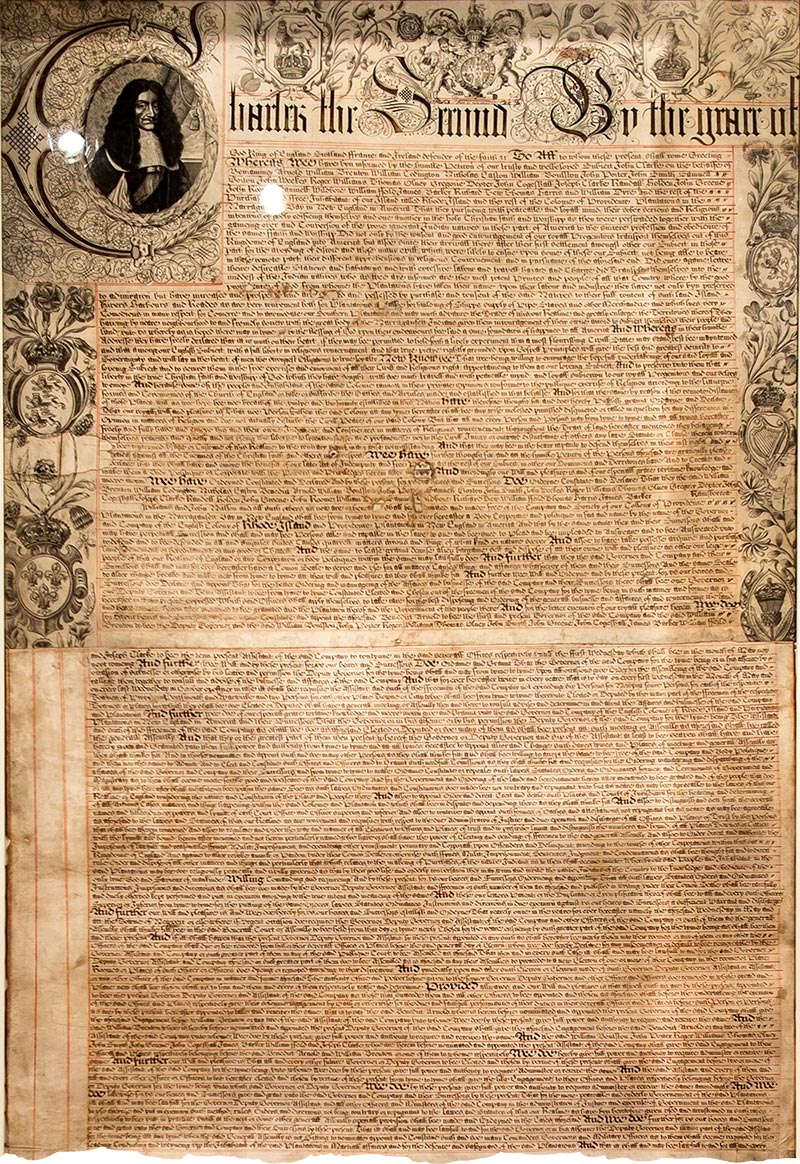

Every colony had received a Charter that established local colonial government and defined the colonists’ rights as Englishmen. When the Crown theoretically shut down the back country to American immigration, it was already too late, and the Proclamation line was crossed with impunity. When illegal post-war taxes were levied on sorts of products, soldiers quartered in people’s homes, and writs of assistance issued, in search of contraband and untaxed exports, certain leaders led an insurgent rebellion against Parliamentary and Royal tyranny. After more than eleven years of contention and conflict of interests, twelve of the thirteen colonies met in Philadelphia in the Second Continental Congress, beginning on May 8, 1775.

The Royal Charter of Rhode Island, issued by King Charles II of England, July 1663

A depiction of the Second Continental Congress voting on the Declaration of Independence

The Congress functioned as a government for the colonies, raising troops, securing an army commander—George Washington—and sending him to take charge of the siege of Boston. They issued money, appointed diplomats, and corresponded with British authorities, seeking a compromise. In July, Georgia joined the Congress, making the total thirteen. The delegates sought for ways to bring peace and reconciliation but as the months passed, some of the more radical members began discussing independence from Great Britain. The Virginia Convention instructed their representatives in Congress to pursue independence, and Richard Henry Lee proposed just that in a resolution on June 7, 1776:

The thirteen original colonies with modern borders also superimposed

“Resolved, that these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved.”

Three overlapping committees were formed to articulate the wording of the Declaration, create a confederation government and forge direct economic ties to foreign countries.

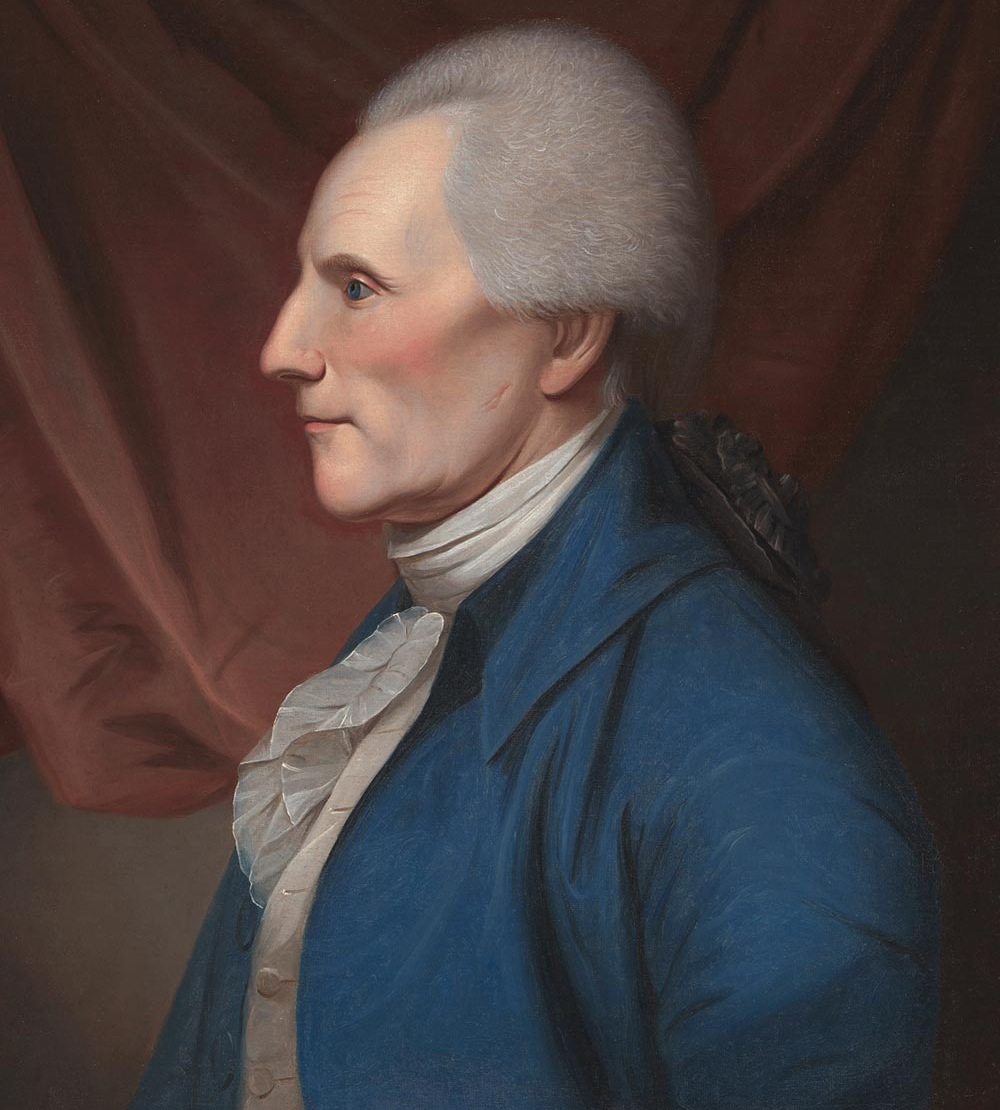

Richard Henry Lee (1732-1794)

The committee appointed to formulate the Declaration contained John Adams of Massachusetts, Thomas Jefferson of Virginia, Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania, Robert Livingstone of New York, and Roger Sherman of Connecticut. While Adams was the most outspoken, all agreed that Jefferson was the best writer and to him fell the initial drafting of the document. The committee presented the document to Congress on June 28, 1776. Congress reduced the document by a fourth over a two-day period. Each state got one vote, so a majority of delegates of each state decided the ballot. A majority of the Committee of the Whole voted for independence and the next day they made it unanimous. On July 4, the Continental Congress declared the independence of the United States to the world.

An artist’s depiction of Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin and John Adams writing the Declaration of Independence in Philadelphia

An artist’s depiction of Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin and John Adams writing the Declaration of Independence in Philadelphia

The document set forth the reasons for separating from Great Britain, a catalogue of indictments against the king, after a general justification for pursuing the action. Some delegates signed it on July 4 and the rest over a period of time from August 2 up through November 4.

The five-man drafting committee of the Declaration of Independence (Adams, Jefferson, Franklin, Livingstone and Sherman) presents their work to the Second Continental Congress

The five-man drafting committee of the Declaration of Independence (Adams, Jefferson, Franklin, Livingstone and Sherman) presents their work to the Second Continental Congress

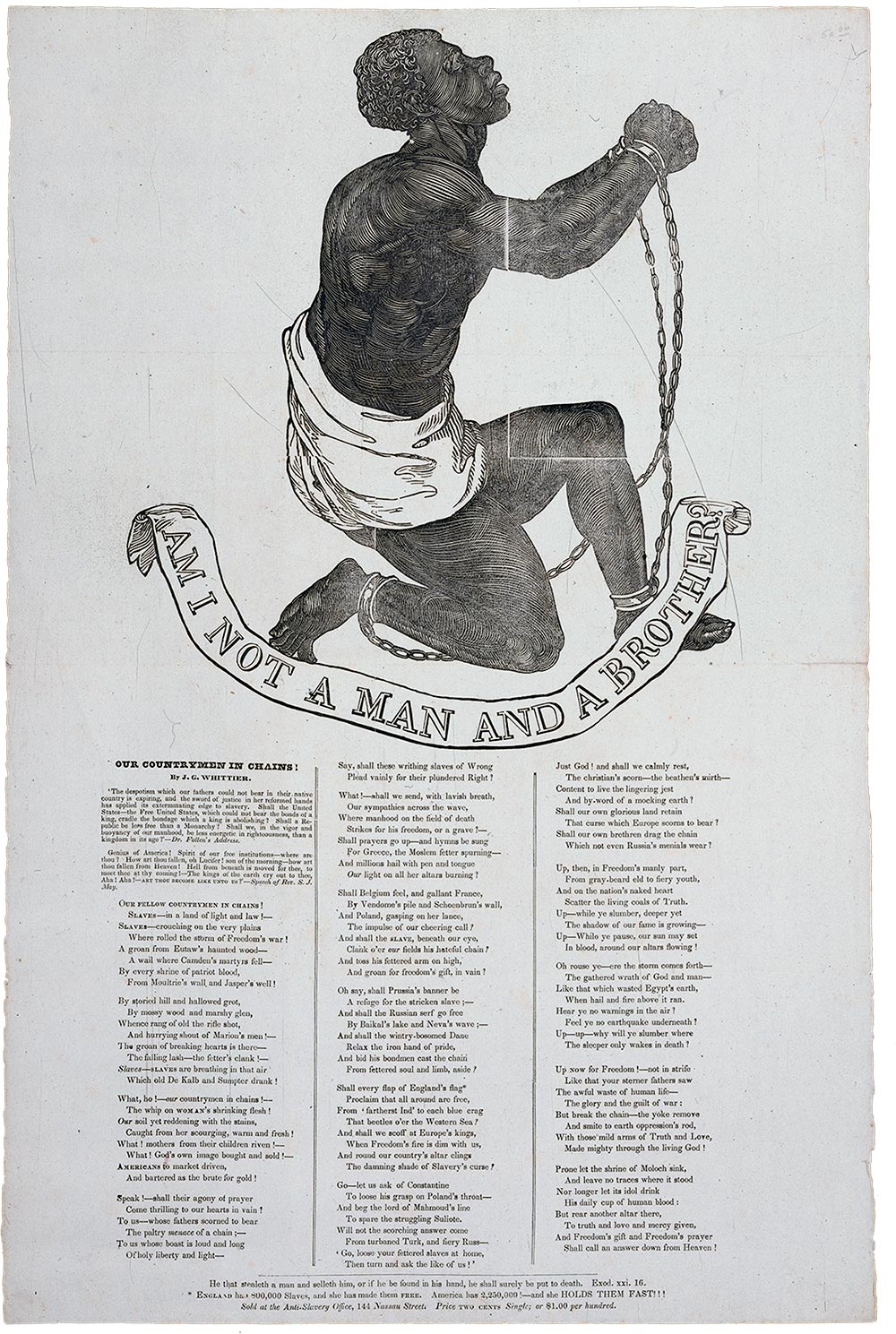

The Declaration was rarely mentioned in the Constitutional debates since it actually had no legal authority regarding the governing of the country. The wording has been influential in the writing of other nations’ Declarations of Independence. In the United States, the indictments were no longer relevant and the nation was independent, so the document had fulfilled its purpose. Interest in the document and the lives of the signers was revived in the 1820s, as the founding generation was passing on and interest in their creation of the Republic using the declaration as a legal indictment of slavery by abolitionists became part of boiler-plate arguments in the middle decades of the century and reading the Declaration into the Constitution by Abraham Lincoln changed the meaning and intent of the preamble and use of the document from his time forward. The Civil Rights Movement, Women’s suffrage, and the LGBTQ movement have all made the Declaration of Independence their central allegiance by defining the words of the introduction and preamble to suit their respective causes.

The Declaration was rarely mentioned in the Constitutional debates since it actually had no legal authority regarding the governing of the country. The wording has been influential in the writing of other nations’ Declarations of Independence. In the United States, the indictments were no longer relevant and the nation was independent, so the document had fulfilled its purpose. Interest in the document and the lives of the signers was revived in the 1820s, as the founding generation was passing on and interest in their creation of the Republic using the declaration as a legal indictment of slavery by abolitionists became part of boiler-plate arguments in the middle decades of the century and reading the Declaration into the Constitution by Abraham Lincoln changed the meaning and intent of the preamble and use of the document from his time forward. The Civil Rights Movement, Women’s suffrage, and the LGBTQ movement have all made the Declaration of Independence their central allegiance by defining the words of the introduction and preamble to suit their respective causes.

Produced in New York by the Anti-Slavery Office, this 1837 poster adopted the seal of the Society for the Abolition of Slavery in England active in the 1780s, and combined it with the antislavery poem, “Our Countrymen in Chains”.

The National Archives Building, Washington, DC

Today, however, there is a trigger warning posted at the National Archives where the Declaration of Independence, The Constitution of the United States, and the Bill of Rights are on display, warning people that:

“some of the materials presented here may reflect outdated, biased, offensive, and possibly violent views and opinions. In addition, some of the materials may relate to violent or graphic events and are preserved for their historical significance. The National Archives is committed to working with staff, communities, and peer institutions to assess and update descriptions that are harmful and to establish standards and policies to prevent future harmful language in staff-generated descriptions.

The Signing of the Declaration of Independence

Re-read the Declaration of Independence, think on the risks taken by the signers, and the war that followed to establish liberty in an independent Republic that has been a shining example to the world, and try not to be offended that you are the beneficiary of their efforts. It may not continue to be so if the writers of trigger warnings remain in power.

Image Credits: 1 Declaration of Independence (Wikipedia.org) 2 Washington Sketch (Wikipedia.org) 3 Rhode Island Charter (Wikipedia.org) 4 Second Continental Congress (Wikipedia.org) 5 Thirteen Colonies Map (Wikipedia.org) 6 Richard Henry Lee (Wikipedia.org) 7 Writing of the Declaration (Wikipedia.org) 8 The presentation of the Declaration (Wikipedia.org) 9 Antislavery Poster (Wikipedia.org) 10 National Archives (Wikipedia.org) 11 The signing of the Declaration (Wikipedia.org)