“Not by works of righteousness which we have done, but according to his mercy he saved us, by the washing of regeneration, and renewing of the Holy Ghost; which he shed on us abundantly through Jesus Christ our Savior;” —Titus 3:5,6

Cane Ridge Revival, August 6-12, 1801

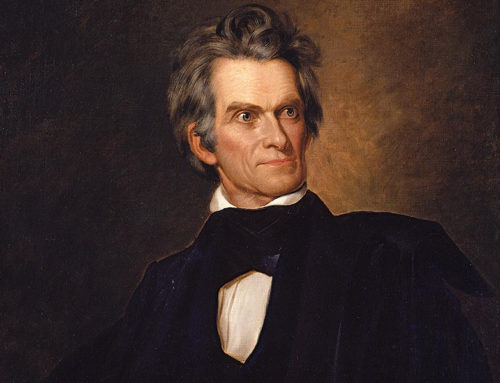

![]() here were still a few people living who remembered the “Great Awakening” of the 1740s when Jonathan Edwards, George Whitfield, Gilbert Tennant, Samuel Davies and other preachers witnessed the “outpouring of the Holy Spirit” in America. Since that time, the United States had come into being, George Washington had recently died, and multiple thousands of Americans had moved westward into Kentucky, Tennessee, and the Ohio Valley. Most church denominations had been unable to keep up with hardy frontiersmen due to a lack of men with formal theological training and the hardships of pioneer travel and settlement. Lack of spiritual sustenance or fellowship and the opportunity to hear preaching after years of benign neglect brought several thousand frontier people together at Cane Ridge, Kentucky in 1801. The spiritual dry spell in America was about to end in dramatic fashion, and prompt a new religious awakening that would last for decades, strike many different geographical areas, and spawn a plethora of counterfeit “revivals” and cults.

here were still a few people living who remembered the “Great Awakening” of the 1740s when Jonathan Edwards, George Whitfield, Gilbert Tennant, Samuel Davies and other preachers witnessed the “outpouring of the Holy Spirit” in America. Since that time, the United States had come into being, George Washington had recently died, and multiple thousands of Americans had moved westward into Kentucky, Tennessee, and the Ohio Valley. Most church denominations had been unable to keep up with hardy frontiersmen due to a lack of men with formal theological training and the hardships of pioneer travel and settlement. Lack of spiritual sustenance or fellowship and the opportunity to hear preaching after years of benign neglect brought several thousand frontier people together at Cane Ridge, Kentucky in 1801. The spiritual dry spell in America was about to end in dramatic fashion, and prompt a new religious awakening that would last for decades, strike many different geographical areas, and spawn a plethora of counterfeit “revivals” and cults.

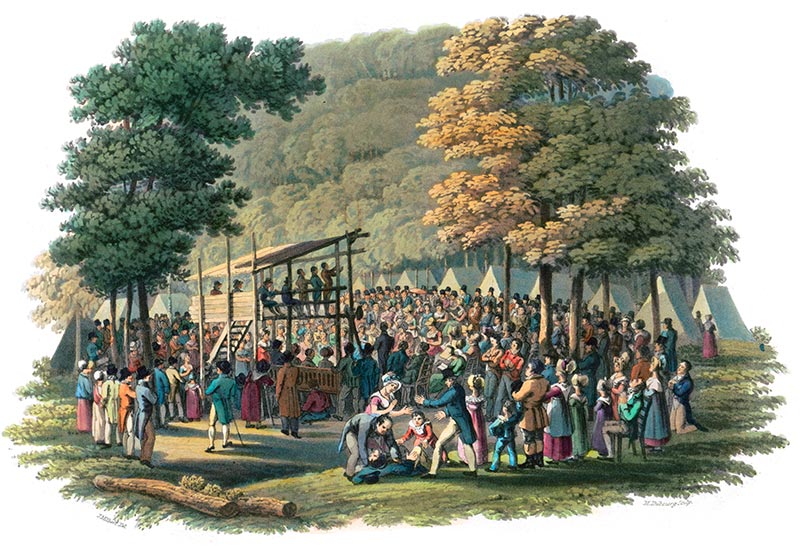

1819 print of a Methodist camp meeting in North America

Small congregations of Presbyterians, Baptists, and Methodists were scattered throughout the region. Some of the Scots-Irish and Scottish immigrants from Virginia and North Carolina had been able to retain some of their religious tradition, but vital “heart-religion” was not as apparent as in generations past. One of the practices that came from Scotland was known as “Holy Fairs,” more usually called “camp meetings” in America, in which multiple congregations would gather for a week or so to celebrate the sacrament of the Lord’s Supper. One such occasion called by frontier pastor James McGready, attracted eighteen Presbyterian and an unknown number of Baptist and Methodist preachers to Cane Ridge in Bourbon County Kentucky, in August of 1801. While there had been revivals of vital spiritual awakening in the late 1790s, no one had ever witnessed the scale and impact of what occurred on that occasion.

Courthouse of Bourbon County, named in honor of the French House of Bourbon in gratitude for King Louis XVI’s assistance during the American War for Independence

The Holy Fair, by Robert Bryden

People travelled many miles to attend the preaching and communion—some estimated between 20-25,000 attendees arrived to camp there for a week, till they ran out of food. The population of the Kentucky capital in Lexington was less than 2,000. Street after street of wagons and tents, full of families hungry for the Word of God, listened intently to the Gospel preaching. None who attended ever forgot the effect on thousands of hearers. Emotions ran high and physical reactions to conviction of sin took various forms among many. It was not uncommon for people to faint or fall into a stupor. Others danced and shouted, while some laughed with the relief from sin. Altogether, the Cane Ridge “revival” resulted in the founding of numbers of new churches of all three denominations. While their theology differed in various ways, the proclamation of the Gospel had a unifying effect during the awakening.

Cane Ridge Meeting House in 1934, the site of the revival in 1801 hosted by the local Presbyterian congregation that met in the building

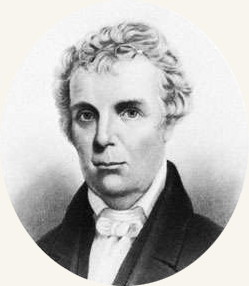

The spiritual impact of Cane Ridge extended to other states, both west and east. Revivals in New York, including New York City, Pennsylvania, Ohio and across the South, occurred in following years. While the Presbyterians were initially the most active and successful church planters with men trained at Princeton and Hamden-Sydney, by 1820 the Methodists and Baptists had streaked past the “confessional” churches in adherents on the frontier, since their ministers, initially, needed only “feel the call” and not be formally educated in the original biblical languages, hermeneutics, or systematic theology. Their hardiness and appeal to the individual attracted many who lived with uncertainty and death daily. With the revivals came new denominations, founded by former Presbyterians and Baptists, as in the “Christian Church” of Alexander Campbell and Barton W. Stone, or the Cumberland Presbyterians. Cults, such as Mormons, Spiritualists, and Jehovah’s Witnesses evangelized alongside the traditional groups. A radical change from the historic Calvinism of the Scots and Scots-Irish produced a “revivalism” by rejecting the doctrines of Grace and replacing them with a more man-centered gospel, manifested in innovations in evangelistic meetings. The “Second Great Awakening” is a subject broad and deep with many historic convolutions, some of which survive to this day. Historians trace many of the “reform movements” of the 19th Century to the religious ferment set loose.

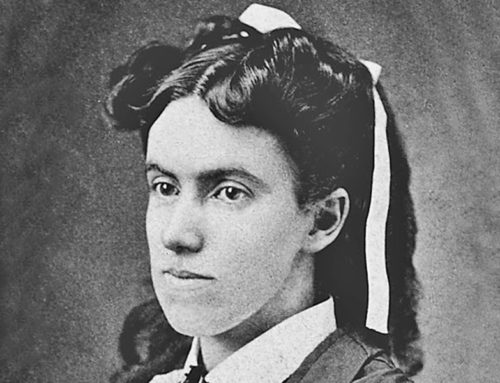

Barton W. Stone (1772-1844), American evangelist during the Second Great Awakening (c. 1790-1840)

Cane Ridge has gone down in history as the largest spiritual awakening, and perhaps the most far-reaching on the frontier, in American history.

- Revival and Revivalism: The Making and Marring of American Evangelicalism 1750-1858, by Ian Murray

- Holy Fairs: Scotland and the Making of American Revivalism, by Leigh Eric Schmidt

- A Religious History of the American People, by Sydney Ahlstrom