“But he answered and said, it is written, Man shall not live by bread alone, but by every word that proceedeth out of the mouth of God.” —Matthew 4:4

The Death of Maximilien de Robespierre,

July 28, 1794

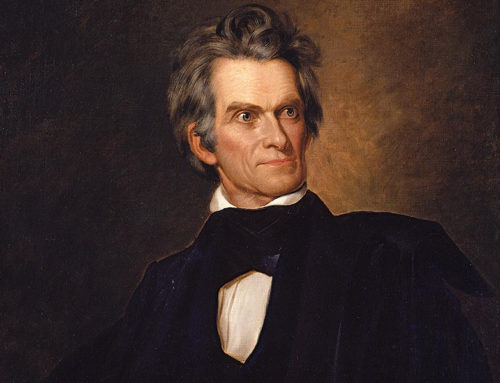

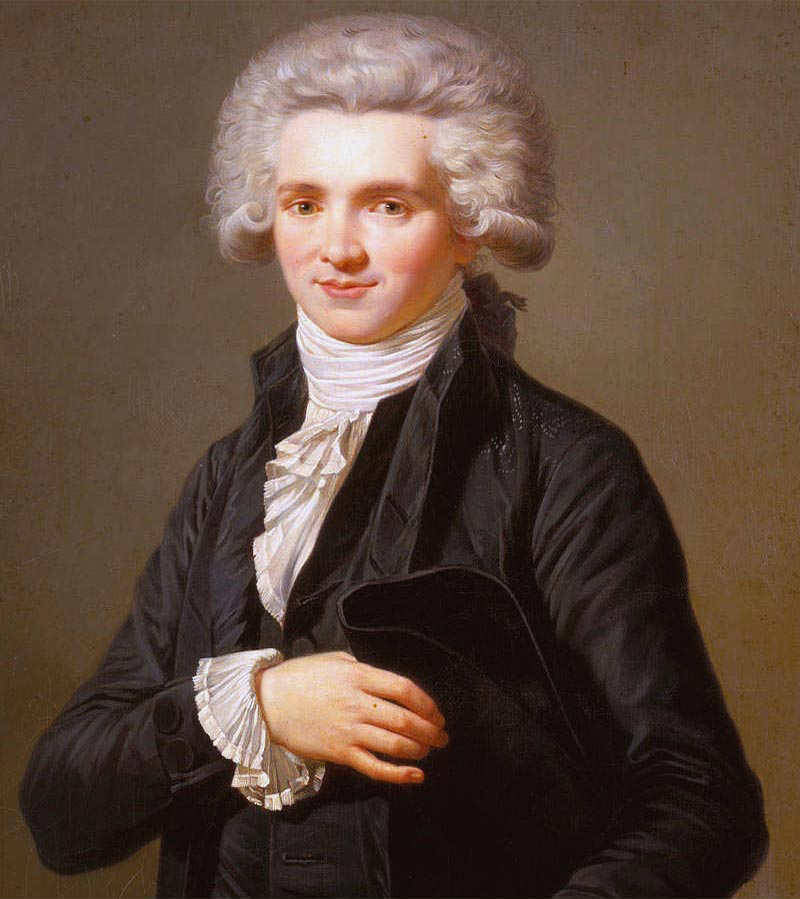

awyers led the French Revolution. They were able to manipulate and inspire the mobs in the streets and co-opt some of the army to bring about political instability, revolt against the monarchy, and support for the destruction of private property, the power of the aristocracy, and the Church. Their revolutionary ideology sought to level all social classes and create in France a utopian nation that would bring about worldwide change, what historian Otto Scott deemed a “republic of virtue.” Eventually the creation of the perfect revolutionary society fell to the power of the “Committee of Public Safety,” led by Maximilien François Marie Isidore de Robespierre who would bring about the execution of thousands of innocent people before he himself fell victim to the guillotine on July 28, 1794.

awyers led the French Revolution. They were able to manipulate and inspire the mobs in the streets and co-opt some of the army to bring about political instability, revolt against the monarchy, and support for the destruction of private property, the power of the aristocracy, and the Church. Their revolutionary ideology sought to level all social classes and create in France a utopian nation that would bring about worldwide change, what historian Otto Scott deemed a “republic of virtue.” Eventually the creation of the perfect revolutionary society fell to the power of the “Committee of Public Safety,” led by Maximilien François Marie Isidore de Robespierre who would bring about the execution of thousands of innocent people before he himself fell victim to the guillotine on July 28, 1794.

Maximilien de Robespierre (1758-1794), French lawyer and politician, and leader of the French Revolution

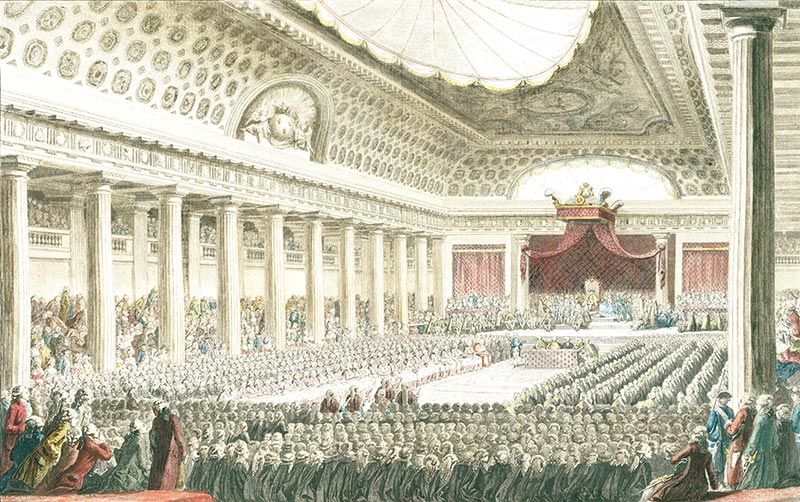

The opening of the Estates General May 5, 1789 in the Salle des Menus Plaisirs in Versailles

Historians have argued for a smorgasbord of factors leading to the revolution, including royal despotism, ideas promulgated by French political philosophers, financial crisis in government and economic crisis among the poor (including the increase in the price of bread, the staple of the masses), and a desire to emulate the success of the Americans to establish an independent republic. In 1789, the Estates General was formed to represent the nobility, clergy and the 95% of the rest of the people (Third Estate). When Louis XVI closed their meeting hall, the Estates met on a tennis court and concluded to write a constitution in non-stop meetings.

King Louis XVI of France (1754-1792), the last king of France before the fall of the monarchy during the French Revolution

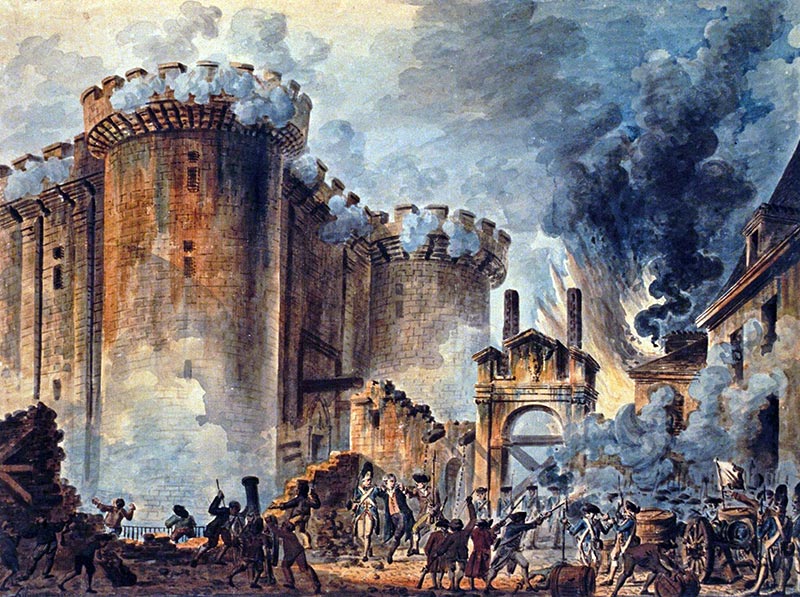

Fearing that the king would send a mercenary army to stop the proceedings, riots, looting, and killing swept through Paris, joined by some of the French guard. The mobs attacked and destroyed the Bastille, a fortress and jail which symbolized royal authority. Only a handful of prisoners were there to be liberated and the small garrison was massacred. Bastille Day, July 14, is still celebrated every year in France.

The storming of the Bastille on July 14, 1789 and the arrest of the French Governor of the Bastille Bernard René Jourdan Marquis de Launay (1740-1789)

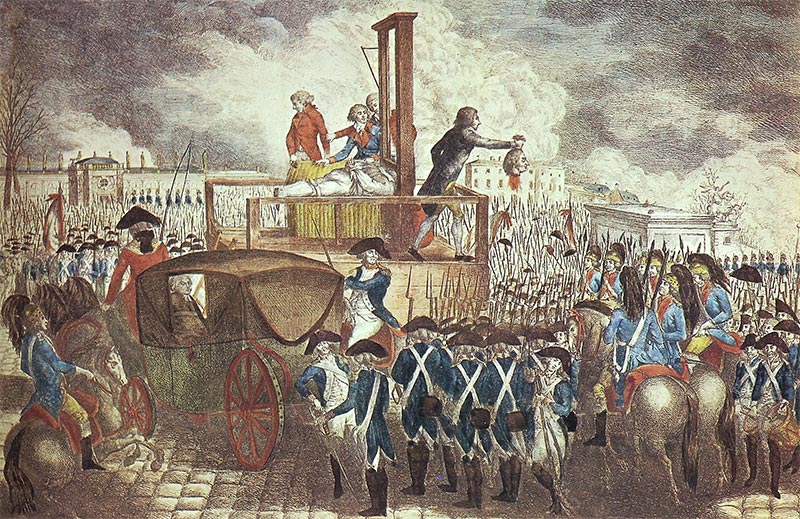

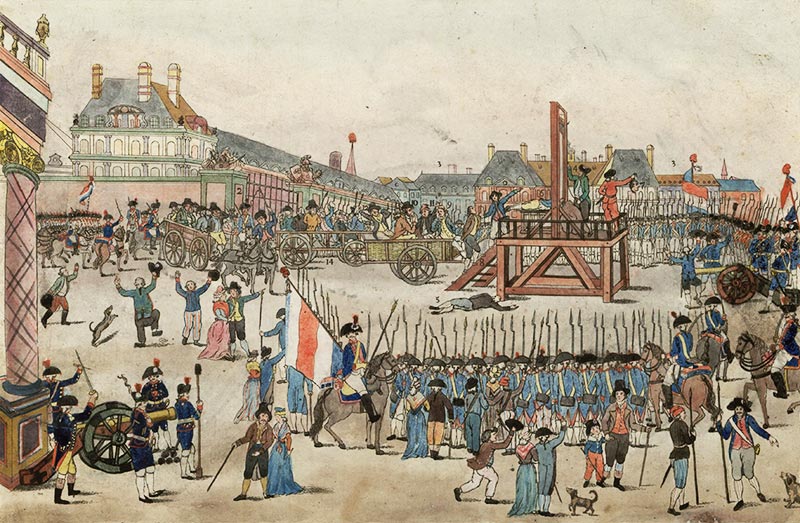

Members of the nobility fled the country and the National Assembly abolished feudalism, taxes, and obedience to royal authority. Mobs and militias developed across France, eventually forming a revolutionary army to repel foreign troops on their borders and enforce the new “republic of virtue.” The Third Estate abolished the other two, executed the king and queen, and continued the restructuring of society using the death penalty for aristocrats, property owners, and anyone connected to royal authority. A period known as the “Reign of Terror,” led by the Committee of Public Safety, lasted from 1792 to July 1794, when about 17,000 death sentences were carried out across France, and perhaps ten thousand more died in prison. An uprising against the revolution in the Vendee region cost the lives of tens of thousands.

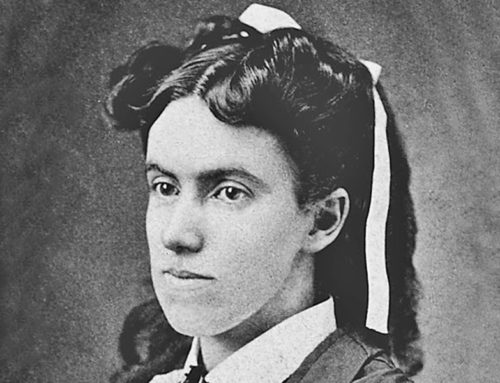

Last queen of France before the fall of the monarchy, Marie Antoinette (1755-1793) was executed by guillotine, some nine months after her husband met the same fate

The execution of King Louis XVI, January 21, 1793

While Robespierre, a leader of the Jacobin Party, led the Committee, most of the people that were publicly executed had their heads chopped off by the guillotine. A popular phrase at the time was “don’t get shaved by the national razor.” Surrounding nations massed on the borders of France, intent on stopping the slaughter. The levee en masse was instituted, placing virtually every male citizen in the army to defeat the coalitions of their enemies.

Pressure was put on Robespierre by the sans-culottes, the “urban workers” to punish anyone who opposed the interests of the poor, as defined by the poor (sans-culottes means “without pants,” i.e. the common people who couldn’t afford fashionable clothes). The Reign of Terror extended to the Roman Catholic Church, the largest land-owner in France and financed by the tithe; priests, monks and bishops were forced to join the revolution or be executed. Notre Dame Cathedral became “The Temple of Reason,” presided over by a “goddess” taken from the street. The new government renamed the months of the year to show their break with the past and to mark the beginning of a new humanist state, guided by reason and extended by war and terror.

Depiction of a typical “Sans-Culotte,” a term derived from the inability of the lower classes to afford culottes — the fashionable silk knee-breeches of the 18th-century nobility

The French Revolution became the template for future revolutions in the following centuries and, like them, “the revolution consumes its own children.” The Committee of safety was brought to its ignominious end by both those who did not think Robespierre was radical enough and moderates who decried the violence in the first place. In the end, he went to the guillotine also, after being shot through the jaw the day before in a failed suicide attempt.

The Fall of Robespierre in the Convention on 27 July 1794 depicts a wounded Robespierre falling to the convention floor

The French Revolution elevated man’s reason as ultimate, and attempted to discard the past with its hierarchies, hereditary kings, extravagances, and laws. The battle cry of the French Revolution was Liberté Égalité Fraternité. History has proven that liberty is the enemy of egalitarianism and collectivism. The end result is a powerful dictator, in this case, Napoleon Bonaparte. The war continues, as does the resistance.

Napoleon Bonaparte leads his troops across the bridge at the Battle of Arcole, November 15-17, 1796

The execution of Maximilien Robespierre, July 28, 1794

Edmund Burke, the great conservative parliamentarian of England wrote of the French Revolution:

“I should therefore suspend my congratulations on the new liberty of France, until I was informed how it had been combined with government; with public force; with the discipline and obedience of armies; with the collection of an effective and well-distributed revenue; with morality and religion; with the solidity of property; with peace and order; with civil and social manners. All these (in their way) are good things too; and, without them, liberty is not a benefit whilst it lasts, and is not likely to continue long.”

1. Robespierre: The Voice of Virtue, by Otto Scott

2. Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution, by Simon Schaama

3. Fire in the Minds of Men: Origins of the Revolutionary Faith, by James Billington

Image Credits: 1 Maximilien de Robespierre (Wikipedia.org) 2 Estates General (Wikipedia.org) 3 Louis XVI (Wikipedia.org) 4 Storming of the Bastille (Wikipedia.org) 5 Queen Marie Antoinette (Wikipedia.org) 6 Louis XVI Execution (Wikipedia.org) 7 Sans-culotte (Wikipedia.org) 8 Fall of Robespierre (Wikipedia.org) 9 Napoleon Bonaparte (Wikipedia.org) 10 Robespierre’s execution (Wikipedia.org)