e is known as the “Father of his Country.” He was from Virginia, a slaveholder and a defender of the institution of slavery, a man of ambition and wealth who sought to fulfill a vision of the future given to him by his father. He was fearless and intrepid, persevering through setbacks and hard times. He was at the birth of a new nation, colleges are named after him; statues honoring him stand tall in the capital city that bears his name, which is Stephen Fuller Austin.

e is known as the “Father of his Country.” He was from Virginia, a slaveholder and a defender of the institution of slavery, a man of ambition and wealth who sought to fulfill a vision of the future given to him by his father. He was fearless and intrepid, persevering through setbacks and hard times. He was at the birth of a new nation, colleges are named after him; statues honoring him stand tall in the capital city that bears his name, which is Stephen Fuller Austin.

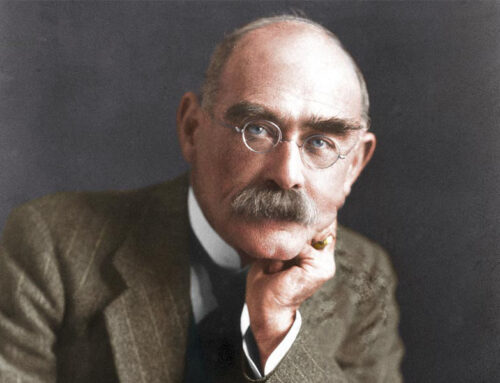

Stephen Fuller Austin (1793-1836), the “Father of Texas”

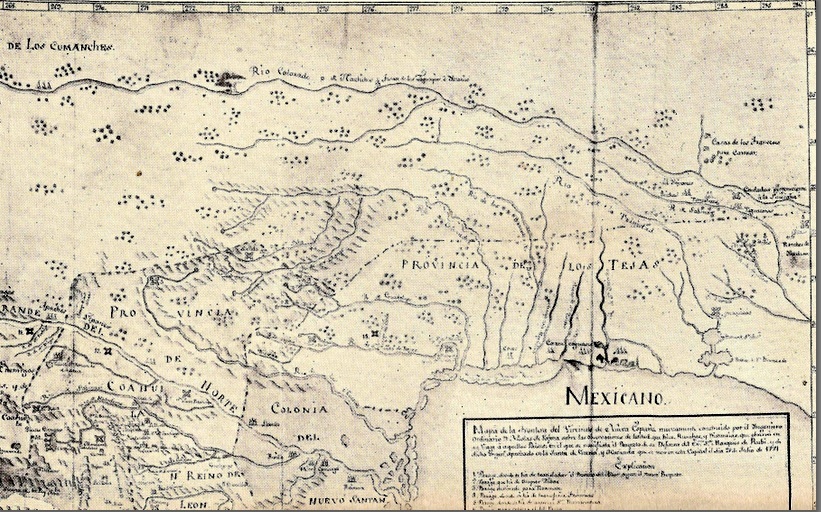

This 1771 map of New Spain’s northern frontier, depicts the coastline of Texas and includes among its notations: “Provincia de los Tejas”

Stephen’s father, Moses Austin, had moved his family from New England to Philadelphia, to Richmond, Virginia, then to southwestern Virginia in Wythe County to mine lead. From 1791 Moses helped establish mills and mines and related industry with his brother. He overextended his debts, broke with his brother and skipped out to Missouri, making a deal with the Spanish government to mine the rich lead deposits of the Louisiana territory. When the area became United States territory in 1803, Moses invested in banking in St. Louis, a business that collapsed in the Panic of 1819, taking his entire fortune with it. Ever on the move, entrepreneurial, and persistent, Moses envisioned leading a colony of Americans to Texas, and persuaded the Spanish government, once again, to back his dream of settling three hundred Anglo families. After receiving permission to settle in 1820, Moses died, but not before imparting his vision to his son Stephen.

Moses Austin (1761-1821), lead mining entrepreneur, pioneer, and father of Stephen F. Austin

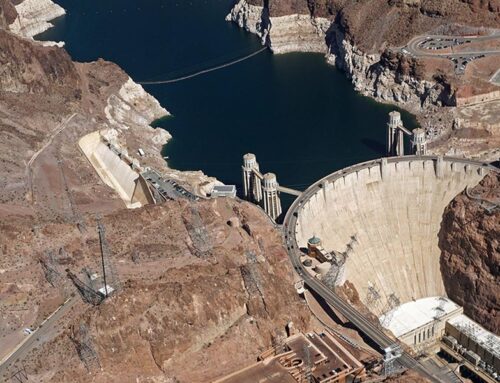

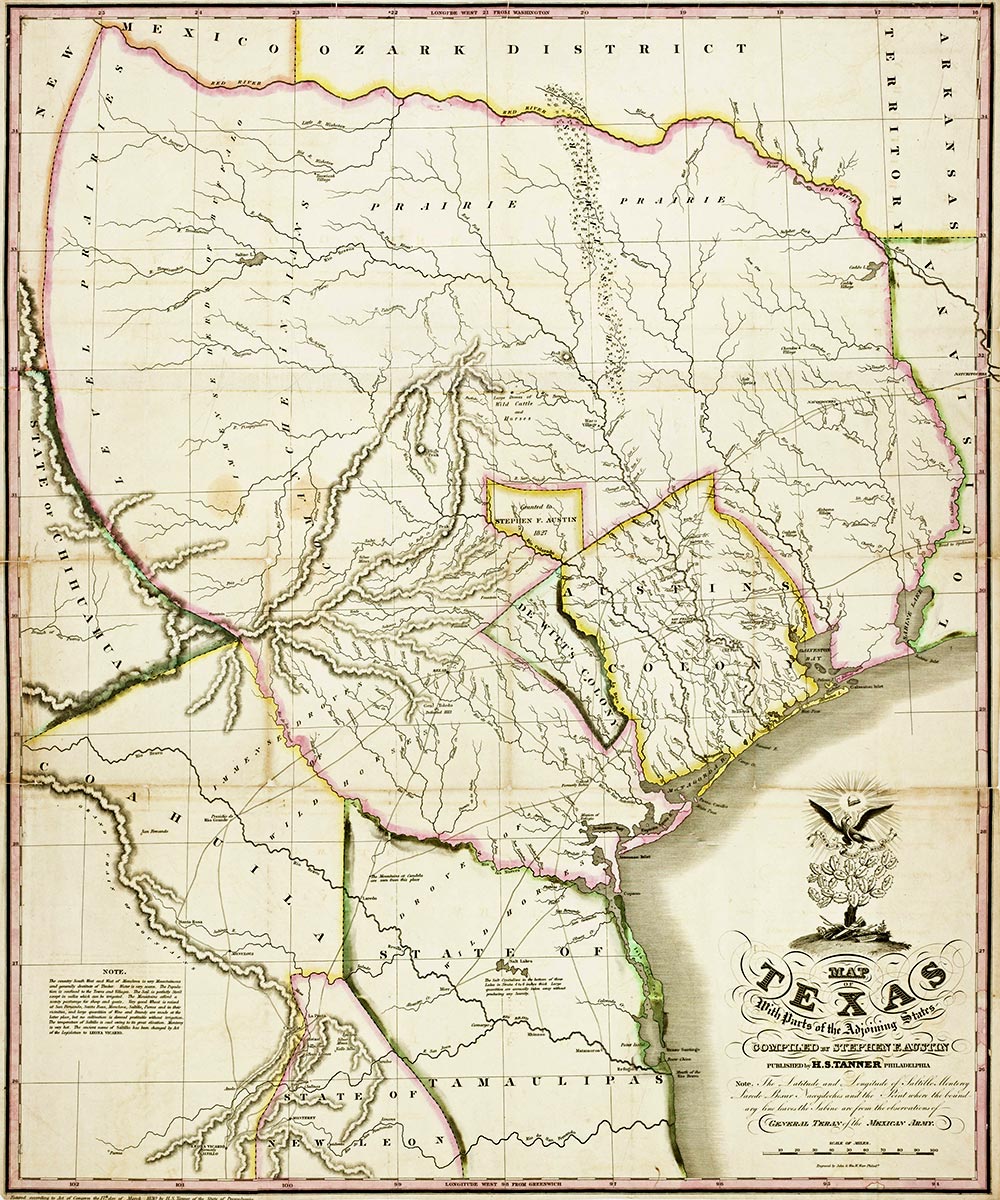

In his contract with the Mexican government, Stephen Austin required the compilation of a map of his Texas colony. A Mexican-government-sponsored commission led by Mexican General Manuel Mier y Terán aided in the effort, and the map was completed in 1829. The following year Austin sent a copy of his map to Philadelphia mapmaker Henry S. Tanner, from which Tanner produced the above map, indicating Austin’s holdings outlined in yellow.

Stephen Austin renewed his father’s impresario grants in 1821, with the help of Jose Navarro, a Mexican friend in San Antonio. In that same year, the Mexicans ousted the Spanish government and declared independence. Austin was able to retain his grants of land and permission to settle three hundred families, with the promise to abide by the settlement criteria set down by the new legislature. He brought in those first families and added another nine hundred between 1825 and 1829. They displaced the native tribes along the gulf, killing many, and also built settlements and homes along the eastern rivers of Texas, promising to abide by Mexican law, but often just transplanting their American culture, including slavery and Protestantism, both banned by the Mexican government. The Texians were allowed local self-government and built social institutions on their own. Benign neglect by the faraway governors in Mexico City forced the colonists to defend themselves and establish their own economic prosperity.

José Antonio Navarro (1795-1871), native of San Antonio de Béxar (now San Antonio, Texas), was a rancher, statesman, and early proponent of Texas independence who became a signer of the Texas Declaration of Independence

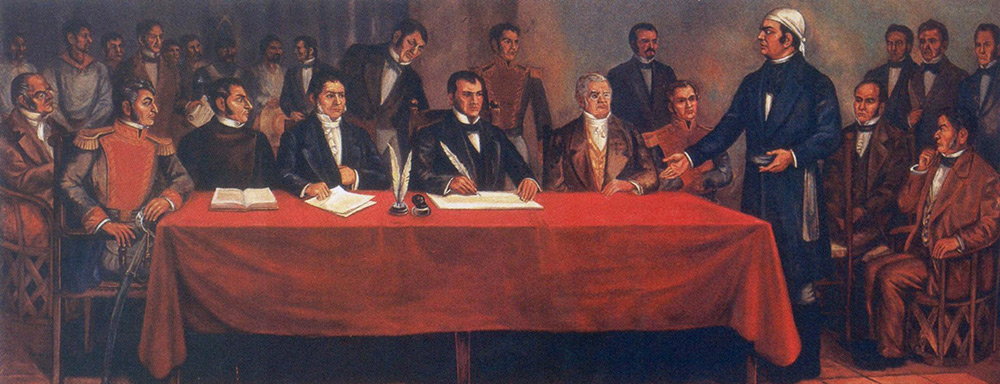

November 6, 1813, members of the Congress of Anáhuac sign the Solemn Act of the Declaration of Independence of Northern America, the first Mexican legal historical document formally declaring independence from the Spanish crown, a move precipitated by Napoleon Bonaparte’s invasion of Spain in 1808 which touched off a crisis of legitimacy of crown rule

With all the political turmoil that erupted throughout Mexico in the decade since independence, break-away movements appeared in several provinces, including Texas. The central government insisted on levying new taxes and the collection of customs. They quartered troops at colonial expense and determined to enforce complete obedience through dispatching an army to Texas. Many Texians despised the Mexican culture, and the feelings toward “Anglo-Saxons” were mutual. The entire scenario seemed somehow familiar to the history-conscious, liberty-loving Americans living in Texas.

Administrative map of Mexico during the period of 1835-1846 with light green areas indicating regions where separatist movements were active

A revolt against Mexico and for independence by Anglo-Texans reflected the loyalty-and-support confusion similar to the American War for Independence—many of the wealthiest elites were opposed, especially among the original three hundred. Others tried to remain neutral to see which way the wind would blow, and others stood four-square for revolution and independence. The remarkable Mexican caudillo and General, Antonio López de Santa Anna, had no such ambivalence. Born of a middle-class Spanish family near Santa Cruz, Santa Anna had risen through the ranks of the Mexican army through bravery in battle, hard campaigning, and devotion to duty. He also retained a political savvy that enabled him to tack to the political winds. In 1834 Santa Anna took over the Mexican government entirely, did away with the Constitution of 1824, centralized the state, and abolished all local legislatures. Stephen Austin and most other Texans had previously approved of Santa Anna’s political machinations, though Austin had spent eighteen months in prison for opposing aspects of the changes. When the Texans discovered the new order and an army of invasion under General Cos, and felt the cold steel of military enforcement, the rebellion was on. Austin put out a call for Texans to stand to arms: “War is our only resource. There is no other remedy. We must defend our rights, ourselves, and our country by force of arms.”

Antonio López de Santa Anna (1794-1876), Mexican politician and military leader

March 6, 1836, the small band of Texians (approximately 200) defending the Alamo Mission fell to the overwhelming numbers of the Mexican Army (some 1,800 troops) under the command of General Santa Anna, but not before inflicting some 400-600 Mexican casualties

The bitter War for Texas Independence lasted from October 2, 1835 to April 21, 1836 and immortalized such places as Goliad, The Alamo, and San Jacinto. While Austin lived long enough to see independence achieved, he was overwhelmingly defeated for first President by Samuel Houston, born 120 miles north of Stephen Austin, in Lexington, Virginia but destined for a different role for those GTT (Gone To Texas). The Independence of Texas was declared on March 2, 1836; the Alamo was stormed and wiped out on March 6, the last battle that secured independence at San Jacinto on April 6.

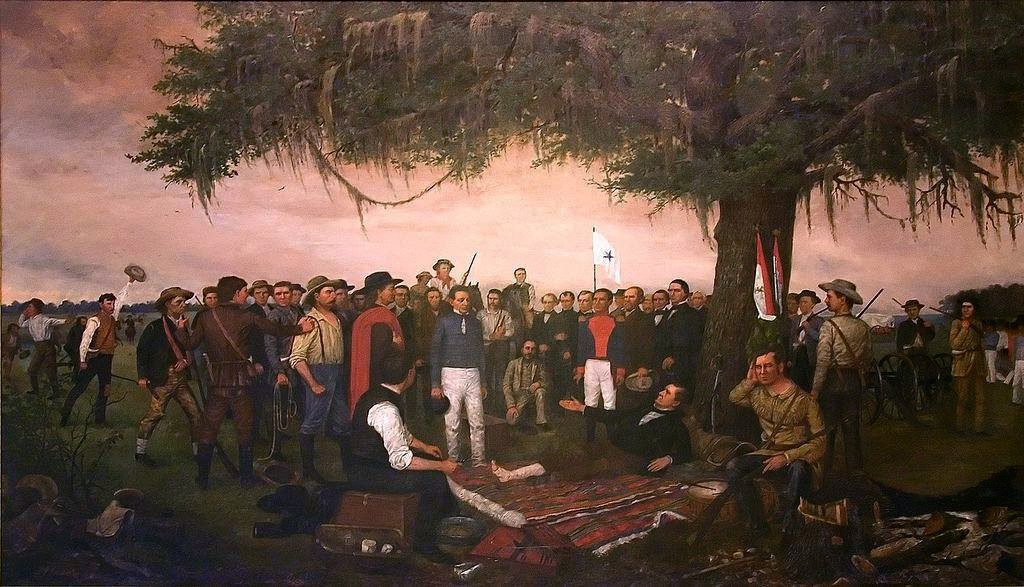

Following the decisive defeat of the Mexican Army at the Battle of San Jacinto, General Santa Anna surrenders to a wounded Sam Houston and the revolution is ended

Image Credits: 1 Stephen F. Austin (Wikipedia.org) 2 1771 Mexican Frontier Map (Wikipedia.org) 3 Moses Austin (Wikipedia.org) 4 1830 Texas Map (Wikipedia.org) 5 José Antonio Navarro (Wikipedia.org) 6 Congress of Anáhuac (Wikipedia.org) 7 Map of Separatist Movements (Wikipedia.org) 8 Santa Anna (Wikipedia.org) 9 Fall of the Alamo (Wikipedia.org) 10 Surrender of Santa Anna (Wikipedia.org)</small